Personal Encounters

With Hinduism

ERE ARE TRUE HISTORIES OF INDIVIDUALS AND FAMILIES who formally entered Śaivite Hinduism over the years. We begin with Hitesvara Saravan, a former Baptist who discovered Hinduism later in life and recently completed his conversion. Hitesvara and the others whose stories lie herein consented to share their firsthand experience in severing his former religious commitments and then entering the Hindu faith. These inspiring real-life stories illustrate the six steps of ethical conversion (see Chapter Seven) in captivating detail. Each story is written from a delightfully different angle. Enjoy.§

ERE ARE TRUE HISTORIES OF INDIVIDUALS AND FAMILIES who formally entered Śaivite Hinduism over the years. We begin with Hitesvara Saravan, a former Baptist who discovered Hinduism later in life and recently completed his conversion. Hitesvara and the others whose stories lie herein consented to share their firsthand experience in severing his former religious commitments and then entering the Hindu faith. These inspiring real-life stories illustrate the six steps of ethical conversion (see Chapter Seven) in captivating detail. Each story is written from a delightfully different angle. Enjoy.§

My Conversion from the Baptist Church

How I Was Uplifted and Transformed by the Śaivite Hindu Teachings. By Hitesvara Saravan.

Gurudeva, Sivaya Subramuniyaswami, has blessed me with the name Hitesvara Saravan, which I interpret to mean One who cares for others born of the Lake of Divine Essence. My former name was Alton Barry Giles, a name from Scottish heritage. §

It was not until I was in the vānaprastha āśrama, at 56 years old, that in July of 1997 I typed the word Hindu into a search engine on an archaic, text-only computer. This brought me into a new conscious realization as I came upon a text in Gurudeva’s website about the five sacred vows of the sannyāsin, which I printed and studied. These words touched me at a soul level. Through exploration of the website over the next few days, I was brought into a small group of devotees in San Diego and then to the local mandir. My conscious journey into the beliefs of my soul intensified. §

I had not met Gurudeva in person. I had not even seen a picture of him until my first satsaṅga in August. I had been aware, however, for many more than twenty years that I had an inner, spiritual guide—a gentle, kind man urging me onward. Now I know that Gurudeva has been with me all my life. I began the joy of being able to communicate with Gurudeva by e-mail and to be introduced to him by phone, but I was not to meet him in person until December of that year. §

Why did I come in person to Gurudeva so late in life? I had many experiences from which to learn, many past life karmas to mitigate. I had many years of living below the mūlādhāra. I had the need to overcome fear of God from my fundamental Baptist upbringing in a very religious family. I had even been told by my mother that my lack of belief and lifestyle meant that I was going to go to hell. She cried. I had to overcome alcoholism and drug addiction and its effects, which I did in 1982, sexual promiscuity by becoming celibate in 1992, renouncing meat eating, also in 1992, and learning to rise above all of the lower emotions, such as fear, anger and resentment. I had to commence on the path toward purity to find and learn many lessons from experience before I would be ready to wholeheartedly and completely dedicate myself to the San Mārga, the straight path. I had previously rejected the idea of any one person being my teacher. Now I know this was just in preparation until I met my one teacher, the guru of my soul, Satguru Sivaya Subramuniyaswami. §

I had been introduced to the Eastern religions in a fleeting way all throughout the 70s and 80s. I had heard Krishnamurti, had glimpses into Buddhism and Taoism, but it never fully formed in my mind that the beliefs of my soul were Hindu beliefs. I had only heard briefly about Hinduism and only from a Western perspective. In the 90s, after I renounced meat and sex, my spiritual path intensified. I read the Yogi Publication Society’s books. I heard about Vivekananda and read his works, as well as Autobiography of a Yogi. I read some of the literature from the Theosophical Society; Light on the Path in particular struck home with me. From January, 1997, until I came into the Śaivite fold I attended SRF (Self Realization Fellowship) services in San Diego, but was put off by the fact that while I believed in the concept of “saints of all religions,” the pictures of Jesus on the altar and the references to Jesus did not sit well with me. §

Simultaneously with meeting Gurudeva’s followers and having accessed the website, I began receiving the daily lessons from Dancing with Śiva. Every one of Gurudeva’s beautiful words spoke to my soul. I realized that these were and had been always the beliefs of my soul. I had found my true path. From that day forward, and with greater intensity after my first beautiful experience of darśana and meeting Gurudeva in December of 1997, I have tried to undauntingly move forward as I have been guided and led. §

I obtained and avidly read and reread Dancing with Śiva and Loving Gaṇeśa. I read “The Six Steps of Conversion.” There has never been any doubt in my mind that this is what I wanted to do, not so much to convert to Śaiva Siddhānta but to return to it formally, albeit for the first time in this lifetime. I attended the local mandir for Śiva and Gaṇeśa pūjās starting the first month after accessing the website and mixed with Hindus during festivals. There was immediate welcoming and acceptance. §

I wrote a point-counterpoint between Śaiva Siddhānta and Baptist belief. I realized that I had never been comfortable with my Baptist upbringing. I had, for example, never comprehended the concept that in the Old Testament God was vengeful, calling down plagues, killing first-born sons, but then it seemed that this God changed upon the birth of Jesus and he was now kind and loving. It made no sense that God would change. I always believed in God, but the God of the Baptist religion did not equate with my inherent knowledge of God. §

I commenced assigned sādhanas, books one and two of The Master Course, the teachers’ guide, the Loving Gaṇeśa sādhana among them, and of course daily reading of Dancing with Śiva. I learned and began daily Gaṇeśa pūjā, rāja and haṭha yoga, and made efforts at meditation. §

I let Gurudeva know that I wished to make a formal conversion. On March 9, 1998, I received the blessing of my Hindu first name based on my astrology and the syllable hi. My first name was Hitesvara, “God of Welfare,” caring for others. I was now ardha-Hindu Hitesvara Giles. I was then permitted to pick three last names for Gurudeva to choose from. I chose Kanda, Saravan and Velan. §

I attended several Baptist Church services locally, including Easter services. I made arrangements to travel to Boston on April 30 to meet with my father and brother and the minister of the church where I was brought up to fulfill the formal severance’s third step of conversion and to inform my family of my decision. I had not been to the Baptist church for 38 years, except for my mother’s funeral and one other occasion. §

My father is a non-demonstrative person. He is very strict. He had never once said to me the words “I love you.” The most physical contact we had since I was a small child was for him to shake hands with me. Mother and father had both lamented that I was going to go to hell because of my lifestyle. I had continued, however, a good though distant relationship with them in later years, but I was concerned that father would be upset by my decision, and there was a possibility that he could disown me. That was acceptable, but I wanted to try to honor and respect him for his ways and to not upset him, and it was important to me that I be clear and try to have him understand my decision and sincerity. I therefore wrote him some letters. I told him about my Hindu beliefs in God, and after meditation it came to me to write him a loving letter in which I reminisced about all of the good times that I could remember throughout my years of living at home. §

I had received some advice and had listened to the testimony of several of Gurudeva’s devotees on their experiences in conversion. There was no question that I did a great deal of introspective searching and meditation on the process and that it was fiery and humbling. However, I remained undaunted and firm, but I did need to expend great effort and newfound willpower. §

I had some difficulty reaching and convincing long distance in advance the minister to meet with me, but before I left on my trip he agreed. §

When I arrived at our family home after greeting my father and brother, I immediately set up a Gaṇeśa shrine and a picture of Gurudeva in my bedroom. The next day before dawn I performed Gaṇeśa pūjā and prayed for obstacles to be removed. I then spoke to my father, having prepared an outline in advance and explained to him the beliefs of my soul and also that I was in the process of receiving a Hindu name and that I would be giving up forever the family name.§

My father’s love remained outwardly hidden from me, however he listened and in his way showed his acceptance by remaining silent and not commenting on anything I had said. I invited him to join me in my meeting with his minister, Reverend Vars. My father declined, however my brother agreed to go with me. On Saturday I went to a brook where I had played as a child and performed Gaṅgā Sādhana, imparting to the leaves and flowing water all of my vestiges of Christianity and giving wildflowers I had picked to the water in thanks. §

The meeting was set for the following Monday. I attended the Baptist church service on that Sunday with my brother and listened to Reverend Vars’ sermon, which was on being joyful, gentle, having good, noble qualities. I introduced myself to him and also met briefly with many of my father’s old friends. My father had stopped going to church at 86 due to fragility and weakness. §

That Monday my brother and I arrived at the church at the appointed time. I believe that Lord Gaṇeśa and Gurudeva were there with me. Reverend Vars was very cordial. I spoke to him, explaining that I was grateful to have had a religious upbringing, talked about my years of spiritual questing, how his sermon had touched me, as it indeed was our belief as well to be gentle and to live a good life with good conduct. I had some trepidation that he might be spouting hellfire and damnation to me. However, I had prepared a great deal and sent prayers to the Kadavul Temple in Hawaii and had prayed to Gaṇeśa to remove obstacles and to smooth the way. I was so blessed. §

I explained to the Reverend Vars my belief that I have, and always had, a Hindu soul, my belief in temple worship, divine beings, and in having a spiritual preceptor. I explained the Hindu beliefs of reincarnation and karma. Reverend Vars listened respectfully and told me that he had had chaplaincy training, where he had learned some about other religions, although he could not personally accept concepts like reincarnation. He turned to my brother and asked how he felt about what I was doing. My brother indicated that he would prefer it if I were to be a Christian but that he would support my choice. §

I asked Reverend Vars if he would write me a letter of release. He stated that he would do so and mail it to me. I thanked him. I then offered him a copy of Dancing with Śiva, Hinduism’s Contemporary Catechism to give him additional insight into the Hindu religion. He accepted and said, “I will read this.” §

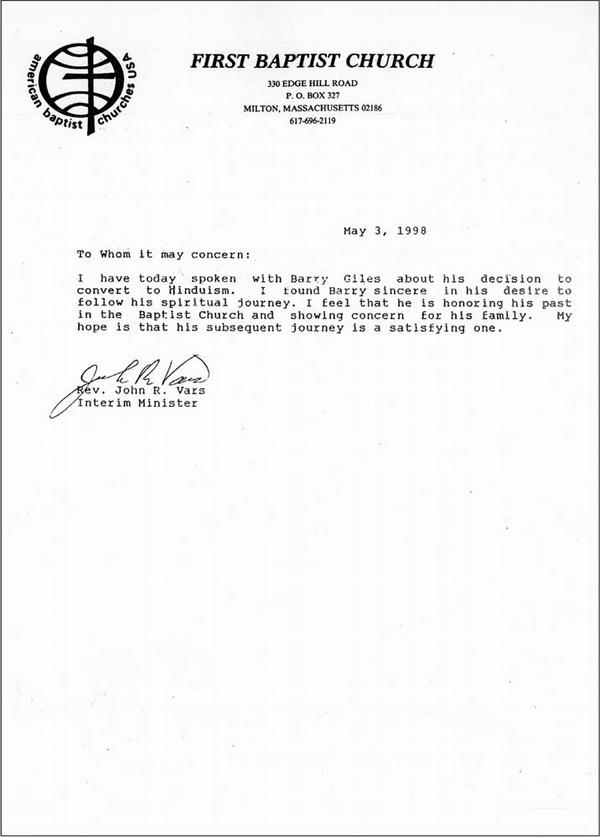

Baptist letter of severance received by Hitesvara Saravan.§

Upon my return to San Diego I received the letter (p. 9) from the Baptist church. On May 28, 1998, I received word that Gurudeva had chosen Saravan for me as my Hindu last name. On May 31 I filed a petition in San Diego Superior Court to change my name. The court date was set for July 28. I also arranged that day for the name change to be published on four weekly dates prior to the court date. §

It was as though my father had waited for me to tell him my news and that he had blessed me, for on July 16, 1998, my father made his transition quietly in his sleep. My mother had made her transition in 1992. §

I appeared in court on July 28. The judge questioned the reason for my decision and promptly signed the decree. I immediately began the process of having legal papers changed, such as driver’s license, social security and all of the many other places and documents that were necessary. I then informed all of my business associates and acquaintances of my decision. §

After my thirty-one-day retreat subsequent to my father’s death, I asked Gurudeva’s blessing to have my nāmakaraṇa saṁskāra. Gurudeva sent a Church member, Sadhunathan Nadesan, and we met that day. I explained to him my Hindu beliefs, and he asked me some questions concerning these. I received Gurudeva’s blessing, and subsequently Sadhu and I talked to the priest of our local mandir. The priest was somewhat surprised, as he had never performed a name-giving ceremony for an adult, but he consulted with his guru, who knew of our beloved Gurudeva, and we provided him with information concerning conversion, including a copy of the Six Steps to Conversion and a copy of a sample certificate. He agreed to perform the ceremony. §

On the auspicious day of August 26, 1998, at a most beautiful ceremony performed by our local Hindu priest and looked over and blessed and attended by the Gods and devas and devotees of Gurudeva, I, Hitesvara Saravan, was “...thus bound eternally and immutably to the Hindu religion as a member of this most ancient faith,” and guardian devas were invoked from the Antarloka to protect, guide and defend me. Jai Gaṇeśa. §

I published in the newspaper a notice of my nāmakaraṇa saṁskāra. Our beloved Gurudeva was and is with me every step of the way. I received the following e-mail message from Gurudeva: “We are all very pleased that you have made this great step forward in your karmas of this life. Congratulations. Now the beginning begins. Don’t proceed too fast. Don’t proceed too slowly. Steady speed in the middle path.” §

My life changed forever. Continuous blessings have been flowing ever since from our beloved Satguru Sivaya Subramuniyaswami. §

Hitesvara Saravan, 58, is the Administrator for the California Department of Health Services in San Diego and has oversight responsibilities for hospitals, nursing homes, home health agencies and hospices. §

Our Release From the Jewish Faith

The Story of Facing Our Rabbi and Being Accepted by the Hindus of Denver. By Vel Alahan.

I was nervous as I sat with my former rabbi to discuss my change of religion. He turned out to be a fine, astute, intelligent man. We explained what we were doing, and he gave arguments in response. Basically he wanted us to give him a chance to start over with us. But we explained what we had been through and that we could not refute the inner knowing that had come from within ourselves about the truth of our Śaivism. We brought a witness with us, an old friend who lives in the neighborhood near the synagogue. We told him that based on our own inner experience we believed in Śaivite Hinduism and in Gurudeva as our guru. We explained how our worship is set up and the striving for eventual knowledge of Lord Śiva, merger in Lord Śiva. Based on the fact that I was a normal person, successful in the business world, with a family and children, he believed what I said and respected my convictions. §

I explained to him why I had come: because I needed to A) test myself in the face of my former religious commitments and B) in the presence of my former rabbi and Jewish inner plane hierarchy, in the Jewish institution, state my inner commitment and my desire to leave Judaism. He had his arguments. We just had to stay strong. I held fast to my inner commitment. My outer mind was fluxing and swaying a bit, but I always had the inner part to hold onto.§

He would not write a letter of severance. He felt that by writing such a letter he would be doing a wrong act himself. But he wished us well, gave his blessings and complimented us on our fine intellectual knowledge of our religion and of Judaism. We introduced the witness and explained why we had brought a witness, so that in the event that the rabbi would not write a letter, the witness could write a letter stating what had happened. We were well prepared, and that is a key point. If one were to go unkempt, unemployed, he would not get the respect. And if you are unprepared, you will fumble a bit. §

Afterward the meeting was over I felt a sense of release. I felt wonderful. I couldn’t believe I had actually done it. Of course, there were the details to be faced afterwards, the announcement and all. But it felt good. And we did not hurt the rabbi’s feelings; though he did say he was sad to lose one of his fold and expressed his view that “Once a Jew, always a Jew.” But he never had to face anything like this before and he said so, that it was something new to him and he would have to take it in on the inside and come to terms with it inside himself.§

Actually, much of the experience of our severance took place earlier, when we had been advised by the Academy to read some books on Judaism and then meet with the author and discuss Judaism with him. We also did extensive point-counterpoints comparing Judaism with Śaivism. At that time, that was a huge psychic battle, almost like a storm. And psychically it was not like fighting another person, but the other forces were defeated. It was a major inner struggle.§

During the early years of our conversion process, we stayed away from the Denver Hindu community, though we visited the Indian food store regularly and paid our respects to the Gaṇeśa shrine there. We realize this would be the Deity of the future Hindu temple. At home, without fail, we did Gaṇeśa pūjā for a number of years with the whole family attending.§

When we reached the stage to contact the Hindu community, and we made an appointment to meet with the Gangadharam family, Pattisapu and Sakunthala. We told them that we wanted to get to know the people and relate to them socially. They talked with us and took us into the community. They became our appa and amma and treated us very nicely. We explained that we intended to have a nāmakaraṇa saṁskāra later with our Gurudeva, and they immediately said, “We will do a nāmakaraṇa. We insist. It will be good for the community as a whole.”§

Interaction included playing tennis with some of the community, dinners, hiking, teas, Telegu new year, Tamil new year. Things progressed, and when the time was right and after we had seen the rabbi and chosen our names, the nāmakaraṇa was arranged. Mrs. Gangadharam planned the day according to Hindu astrology. And a priest was there from the Pittsburgh Temple, Panduranga Rao. Many people were there. A new sari was given to my wife to wear and a shirt and veshṭi was given to me. It was very nice the way they took care of us. During the ceremony, our “parents” signed our names in rice and repeated the required words before the community and Gods. Then we walked around and touched the feet of anyone who was an elder and gestured namaskāra to anyone younger. Food was served afterwards, prasādam from the pūjā.§

Vel Alahan, 52, is a partner in a home building center in Vail, Colorado.§

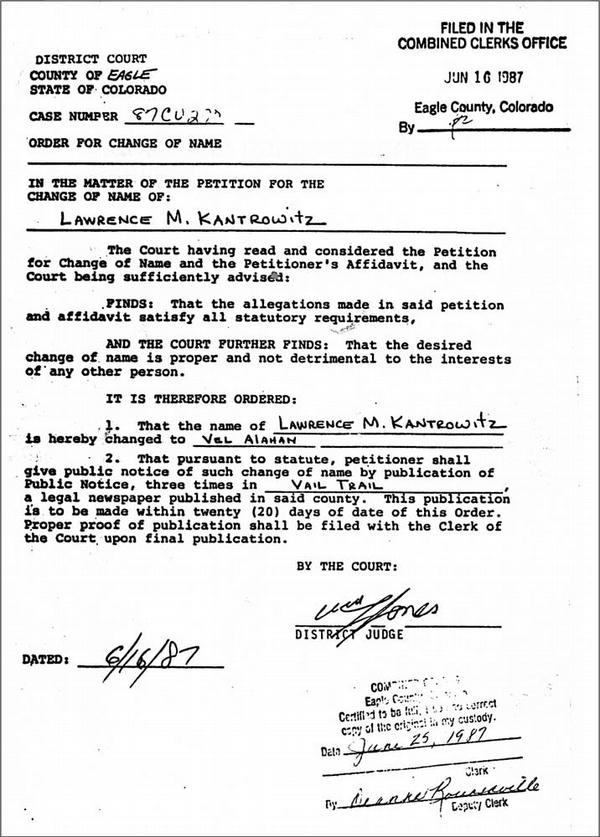

Vel Alahan’s Colorado state name-change document.§

From Judaism to Hinduism

My Successful Struggle for Release From Judaism to Enter Hinduism. By Valli Alahan.

To convert from Judaism to Hinduism was a very big experience in this life. I didn’t know that I would do it; it was nothing I ever planned on. But what happened in studying meditation and then later on, Hinduism, now seems inevitable and quite logical.§

Our Gurudeva believes that it is best for a person to be fully of one religion, not half this and half that. When we began our inner study, I quite easily accepted Lord Gaṇeśa and what little I knew of Hinduism. I was ready to sign on right then. What I didn’t know was that it is a very big process to consciously leave one’s birth religion, especially Judaism at that time, with the confusion surrounding it as being a race-religion. So we were caught temporarily.§

With the grace of Lord Gaṇeśa and Lord Murugan, our opportunity to convert moved along very slowly and with veiled sureness. I knew my true beliefs were in Hinduism and that I, the soul, had no binds. I felt that even if I could not convert in this life, I would hold my beliefs and it would work out later on. I also believed that Gurudeva would not have us go through this for nothing. Still it was discouraging to be halfway “there.” I wanted to be the same religion as my Gurudeva. The longer it took, the more conviction and appreciation for Hinduism developed.§

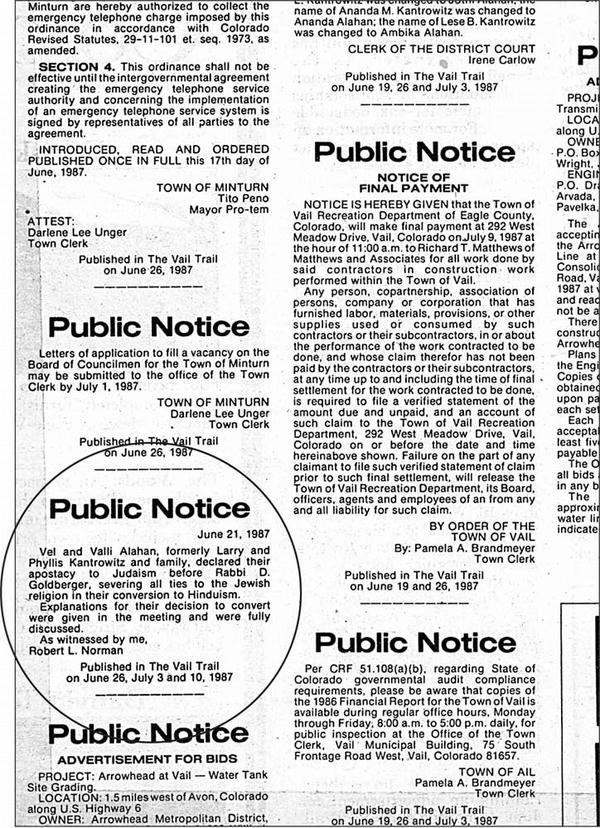

Vel and Valli’s notice announcing their conversion, authored by Robert L. Norman, the witness to their meeting with the rabbi. §

We had to counterpoint our beliefs: Judaism and Hinduism. We (my husband and I) spoke to a rabbi in Israel over the telephone, after reading his book claiming Judaism predated and was the true source of Hinduism. And we wondered if we would ever resolve the conflicting karma of the birth religion and the religion of our soul. One morning I woke up from a dream where I was yelling at the Jewish angels in a fiery way, asserting that “I am not Jewish!” I read from the Tirumantiram, and it gave courage and security. This went on for seven or so years. §

Then, with the grace of our Gurudeva, we were informed that we could amalgamate with the Denver Hindu community. It was a great joy to be around a generation of Indian Hindus that were very kind, open and understanding. Eventually they arranged for our nāmakaraṇa. The name-giving sacrament came after we formally declared apostasy to a rabbi in Denver. It was almost anti-climactic after the long wait, but still a little nerve-wracking because who could know what his reaction would be. We had a detached witness attend, and basically, without insult, the rabbi let us go. We published our change of religion in the local newspapers and with great joy began using our full Hindu names. This was a very meaningful experience that caused me to personally examine and pull up old roots and claim Hinduism as my true path.§

Valli Alahan, 53, is a housewife, mother and grandmother in Vail, Colorado.§

My Excommunication from Greek Orthodoxy

Sent Back To My Old Church, I Learned Hinduism Is The Only Religion for Me. By Diksha Kandar.

My present Śaivite Hindu name is Diksha Kandar; my former name was William Angelo Georgeson. I met Gurudeva in 1969, studied with him in California and India, and entered one of his monasteries in January of 1970. At that time a full conversion to Hinduism was not required, so I served in his monasteries until 1976, at which time he decided that a full conversion was necessary to thoroughly cleanse and clarify the minds of his devotees who had been involved in other religions prior to their exposure to Hinduism. I had been born and baptized in the Eastern Orthodox Christian religion, which is the original Christian religion that first emerged in Greece after the death of Christ. But beyond being baptized in it as a baby, I never participated in it and didn’t know much about it. Yet as a monk, I had come to understand that this potent baptism had connected me up with inner world guardian angels who were obligated to guide me through life according to their Christian mindset, which I had previously adopted simply by being born into a Greek Orthodox family.§

In 1976 Gurudeva informed me that because the Eastern Orthodox Faith is such an old and strong faith, it was considered a race-religion that I was bound to for life, and that I should return to that faith to participate in it fully and permanently. This was heartbreaking for me, and I remember openly crying about this unhappy situation of not being allowed into Hinduism.§

I obeyed and returned to the city where I was baptized to practice Eastern Orthodox Christianity. I worked closely with the priest there and helped him with the church services. I very carefully studied this faith from its origins and learned its beliefs, which were very different than my Hindu beliefs, Orthodox Christian religion, which is the original Christian not only different, but very conflicting on many important points. Since I understood that Hinduism was not an option to me, I never discussed my Hindu beliefs with my Christian priest, because I could see that there was not a resolution in the discussion of them. §

But in studying it out, I learned about a deep, mystical tradition that went back centuries in Greece. I felt if I could find a Christian monastery that lived the ancient spiritual tradition of the Church, then I would enter into that Christian monastery. I offered written prayers to Lord Gaṇeśa to help make this happen. Soon I was corresponding with an author in England who said he knew of such monasteries in Mount Athos, Greece. After six months of serving in the Greek Orthodox Church, I communicated all of this to Gurudeva. When he saw that I was clinging to my Hindu beliefs and did not share the beliefs of the Eastern Orthodox faith, he told me that now that I clearly understood the differences between the two faiths, if I wanted to, I could return to Hinduism after getting a letter of excommunication from the Christian Church, and after being refused the Christian sacraments offered by my priest and after getting my name legally changed to a Hindu name. What a happy day, and I did not hesitate to set all this into motion. §

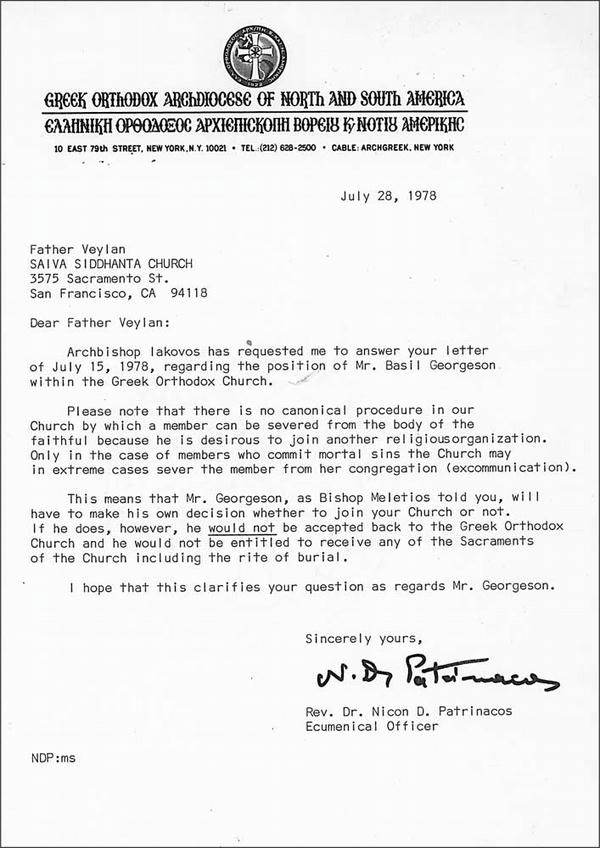

But the priest would not write such a letter, because to do so would be to consign me to everlasting hell, which he could not do in good conscience. The priest’s wife came to me in tears, saying she was not crying because she was going to miss me but because of the condemnation of my soul to everlasting hell. I tried to console her, but it was no use. So then I went to the Church Bishop in San Francisco to see if he would write a letter of excommunication, but he would not discuss the issue with me. After another six months of effort, the Archbishop of North America in New York finally wrote a letter (see p. 20) that said I was no longer a member of the Eastern Orthodox Christian faith—another very happy day. It is this act by the Archbishop which severed my connection with the inner worlds and guardian angels of Christianity, and I felt a definite release.§

Diksha Kandar’s letter from the Greek Orthodox Church.§

My brother, an attorney, had my name legally changed for me. Finally, I had my nāmakaraṇa saṁskāra on January 5, 1979—Gurudeva’s birthday—at Kadavul Hindu Temple in Kauai, which formally entered me into the inner and outer worlds of Hinduism and connected me up with Hindu guardian devas to guide me through life in accordance with my Hindu mindset, which to me accurately reflects the reality of all that is in all three worlds. I was given mantra dīkshā, initiation into the sacred Pañchākshara Mantra, by Gurudeva on September 9, 1982, at the famed Śiva Naṭarāja temple in Chidambaram, South India. These were two of the most important days of my life. §

The whole excommunication process took exactly one year—to the day—to accomplish. There is no religion on Earth that comes close to comparing with the greatness of all that is Hinduism, most especially Śaivite Hinduism. In what sect of Hinduism would you find a woman weeping because someone’s soul was eternally lost? §

After returning to Gurudeva’s monastery, I served for many years as a temple priest at the Palaniswami Sivan Temple in San Francisco and later in Concord, California. I was always treated with the utmost respect by the Indian community who came to the temple. They were always very impressed to hear my story of all the effort that I went through to become a Hindu, and I felt totally accepted by them as a Hindu and as a temple priest. Other Hindu priests also totally accepted me, and I am indebted to one very fine priest, Pandit Ravichandran, for his help in training me in priestly demeanor, protocol and the learning of the Sanskrit language for doing Hindu pūjās. Most importantly, I am indebted to my satguru for making it possible for me to be a Śaivite Hindu through and through, legally, physically, mentally, emotionally, socially, consciously, subconsciously and spiritually in this and inner worlds. §

Diksha Kandar, age 58, lifetime brahmachārī for 31 years; served 23 years as a sādhaka in Gurudeva’s monasteries, including serving as a priest in the temples in San Francisco, Concord and Virginia City. He presently works as a waiter in Seattle, while organizing outreach satsaṅgs.§

Changing Over to a Śaivite Name

With My Family’s Blessings, I completed the Legal Processes and Had a New Name-Giving Rite in Malaysia. By Sivaram Eswaran.

I was born into a Malaysian Hindu family and did not belong to any Hindu sect or religious group. Therefore, I didn’t convert to become a Hindu and was free enough to chose to be a Śaivite Hindu. I am a student of Himālayan Academy preparing to become a member of Śaiva Siddhānta Church. One of the requirements was to bear and legally register a Śaivite Hindu name, first and last, and use it proudly each day in all circumstances, never concealing or altering it to adjust to non-Hindu cultures, as per sūtra 110 of Living with Śiva. §

My original birth name was Raj Sivram Rajagopal. This name was incompatible with my Hindu astrology naming syllable, and the last name, Rajagopal, is a Vaishṇavite name. Therefore, I had to do a complete name change. §

At this point my mother and relatives were unhappy about my proposed name change. Commonly in Eastern Hindu culture, especially in my family, a complete name change of an adult is discouraged. It’s because they feel that this would indicate disrespect to parents and family elders, difficulties to legalize the new name, and it would be a hot topic among the surrounding society. However, I managed to convince them with my strong intentions of becoming a Śaivite Hindu, a member of Śaiva Siddhānta Church, to have a name compatible with my astrology chart and the numerological naming system. Understanding and respecting my decision, my mother and relatives gave their full blessings for the name change. With the blessings of my beloved Satguru Sivaya Subramuniyaswami and the guidance of Acharya Ceyonswami and Sannyasin Shanmuganathaswami, I accepted Sivaram Eswaran as the best and most suitable Śaivite name for myself. §

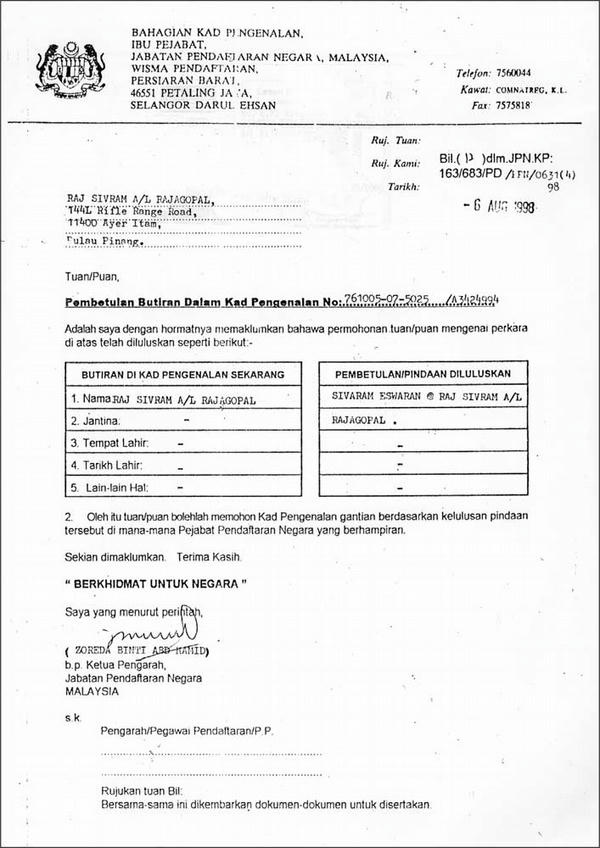

Sivaram Eswaran’s decree of name-change, Malaysia.§

According to Malaysian law, any addition, correction or complete name change in the birth certificate can only be done within the age of one year old. The birth name remains the same in the birth certificate and the new name is only considered an additional name to the original one, if a person intends to change his name after the age of one year old. However, this additional name would only be approved with valid reasons and supporting documents attached to the formal application§

Knowing all this, I made a name change application to the Malaysian Registration Department. This application was attached with my valid reasons and supporting letters from Satguru Sivaya Subramuniyaswami, a relative and a close friend. About five months later, I received the approval letter from the department. At this point I was given a temporary identity certificate, and a year later I received my new identity card.§

My name remained the same in the birth certificate but the addition was done in the identity card as Sivaram Eswaran @ Raj Sivram s/o (son of) Rajagopal. Once I received the new identity card, I went on to correct my name in all other departments, documents, certificates, passport, driving license and bank books. Everything went on well. §

With the blessings of my beloved Gurudeva, on 26 May 1999 morning, my nāmakaraṇa saṁskāra was conducted by the priests at Waterfall Śrī Gaṇeśa Temple, Penang, Malaysia. The ceremony was done in a complete Śaivite tradition with a homa fire. The ceremony was witnessed by my mother, family members, close relatives and friends, and by the head of my Church extended family, Kulapati Thanabalan Ganesan and his wife. §

After the name change, everyone started calling me Sivaram Eswaran, and my signature was also changed. I could also feel some physical changes in myself. The change didn’t end here, but dragged on and started to uplift my life. After my nāmakaraṇa saṁskāra, I felt like a newborn baby at the age of 23 on the spiritual path. I could really feel the change and differences in my daily life when I compare this period to the time when I was known as Raj Sivram s/o Rajagopal. My life started improving well, plans started to manifest, needs were catered on time and life now seems to be more successful then ever. I really prefer and enjoy this new birth after the death of Raj Sivram s/o Rajagopal on 26 May 1999. Believe it or not, it’s really a wonderful life after a name change!§

Sivaram Eswaran, 24, lives in Penang, Malaysia. He is a final year undergraduate with University Utara of Malaysia pursuing a Bachelor’s Degree in Public Management. §

How I Found My Guru

Rejecting Christian Science Early in Life, I Discovered Hindu Yoga and a Śaivite Master. By Easan Katir.

When I was fourteen, an out-of-body experience revealed that there was more to life than this world, so I set out to find out all I could about inner things. I read lots of books, and the one book I used for spiritual practices said “this book is good, but it is much better if you have a spiritual teacher, a guru.” I didn’t have one.§

I had taken Hindu yoga books to the Christian Science Sunday school my parents sent me to, and remarked to the teacher, “These books are saying the same thing as your books, aren’t they?” He said, “No, they’re not, and don’t bring those books here again!” So I didn’t, and I also never went back.§

When I was nineteen I attended a haṭha yoga class at Fresno State University once a week. One week I showed up, and someone at the door said, “The class has been cancelled, but there is a speaker here instead, and you can stay if you want to.” Not having anything else to do, I stayed. A few minutes later, in walked this tall being with white hair and huge eyes. He sat down in full lotus in the front of the room. He began speaking in a language I’d never heard before. A young monk sat next to him and translated into English. The language was Shūm, the language of meditation. I thought this was awesome, and knew that I had found my spiritual teacher.§

I studied through correspondence, then went on Innersearch pilgrimages to India, Sri Lanka and Switzerland. I was a monk for four years at Gurudeva’s monastery, Kauai Aadheenam in Hawaii, where I “grew up” and was educated. I vividly remember the day in 1975 when Gurudeva took a machete in hand, carved the San Mārga path through the Hawaiian jungle and discovered the svayambhū Śivaliṅga. My formal adoption of Hinduism took place at the Chidambaram Naṭarāja Temple in South India in an initiation ceremony conducted by the dīkshitar priests and Gurudeva.§

For a few years, I didn’t see Gurudeva or know of his whereabouts. I pilgrimaged to the Lord Gaṇeśa temple in Flushing, New York. Sitting in front of the Śivaliṅgam after the pūjā, I saw a vision of Gurudeva in orange robes with his hand on my head. About five minutes later, I felt something on my head. I opened my eyes, looked up, and there was Gurudeva in orange robes, with his hand on my head. He said, “Because you have come to this temple, your whole life will change.”§

Soon afterwards, a marriage was arranged in Sri Lanka to a Hindu girl. Now, twenty years later, we have two children who are carrying on the Hindu culture in the deep, mystical way Gurudeva has taught us. We’ve been blessed to help with parts of his grand mission as well. We toured China, Hong Kong and Malaysia to raise funds for Iraivan Temple, carried the yantras for Kadavul Hindu Temple from India, helped found the Concord Murugan Temple, resurrected the British subscription base of Gurudeva’s international magazine, HINDUISM TODAY, helped Sri Lankan refugees and with Iniki hurricane relief in 1992 at Kauai Aadheenam, and helped the Mauritius devotees with the installation of the nine-foot-tall Dakshiṇāmūrti at Gurudeva’s Spiritual Park on that beautiful island.§

Truly, through Gurudeva’s ever-flowing blessings, I’ve experienced much of the four noble goals of human life written of in the scriptures, with Śiva as the Life of my life on the path of Hindu Dharma, the broad four-lane expressway to Śiva’s Holy Feet. Aum Namaḥ Śivāya.§

Easan Katir, 48, lives in Sacramento, California, a Certified Financial Planner with American Express. He entered Hindu Dharma in 1972. §

My Whole Family Became Hindus

Years of Study, Introspection and Praying, Brought Us Into The World’s Greatest Religion. By Isani Alahan.

I was introduced to Gurudeva’s teachings in 1970 through a local haṭha yoga class held at the Parks and Recreation Department in the town where I lived, Carson City, Nevada. The woman teaching the class would lend the students weekly lessons written by Gurudeva, then known as Master Subramuniya, which we would return the following week in exchange for another.§

As time went on I read more about yoga and the wonderful benefits for the body and mind, which I could feel after a few weeks. At this time I decided to become a vegetarian. I was sixteen years old. A few years passed in which I completed high school, experienced travel to Mexico and across the US and the worldly education of Śrī Śrī Śrī Vishvaguru Mahā-Mahārāja.§

In 1972 my interest in studying Shūm, Gurudeva’s language of meditation, manifested. After signing up to study The Master Course audio tape series, I attended the weekly satsaṅga in Virginia City, Nevada, where the vibration was very actinic. During the first satsaṅga, the monks chanted Shūm. I had a memorable vision of Lord Śiva Naṭarāja on the banks of the sacred Gaṅga. My life had changed.§

I was, needless to say, impressionable, and Gurudeva, in his tape course, repeatedly said, “Travel through the mind as the traveler travels the globe.” I went to Europe for four months, experiencing the great civilizations of Greece, Italy, Morocco and Turkey. I had my first encounter with people of the Muslim faith. I learned a lot and repeatedly read Gurudeva’s books.§

When I returned to the US, I moved to the Bay Area to be near Gurudeva’s San Francisco center, as the monastery in Virginia City had been closed to women at the time. I met Gurudeva in the spring of 1973 at a festival at the San Francisco Temple. I went on Gurudeva’s Himālayan Academy Innersearch Travel-Study Program to Hawaii that summer. Then, per Gurudeva’s instructions, I moved back home with my parents.§

In January, I attended another Innersearch to Hawaii. I really enjoyed what I was learning, and I took my brahmacharya vrāta. I studied at home, but there wasn’t a strong support group at the time, and I lacked the inner strength to really stay on track on my own to do the daily sādhanas well.§

In 1975 I married my husband of 25 years. My husband was accepting of my beliefs, but wasn’t interested in studying with Gurudeva at the time. I continued my studies, and in 1980 I legally changed my name to Isani Alahan from Ardith Jean Barton, but kept my husband’s last name, Pontius.§

In December of 1982 I completed my conversion to Śaivite Hinduism from Catholicism. I worked closely with the yogīs and swāmīs in Kauai as they guided me through the relatively easy process. I prepared a statement of apostasy and took it to the local priest. He looked at it and agreed to sign my formal release from the Catholic Church. As I took a deep sigh of relief and quietly said that I was grateful the process had been so easy, he hesitated and asked me to leave the room. When I returned, he had changed his mind. He told me he had called the Bishop in Reno and was told he could not sign the paper. Later I learned this was not true, and the Bishop had been out of town.§

The swāmīs encouraged me to try another priest in the town where I was born. He was understanding, but also declined. During the next few weeks, all but one of my family members were very encouraging and understanding. Only my eldest sister, who was the last remaining practicing Catholic of my siblings, was emotional and angry. My parents even apologized for not being able to help me in some way.§

Within a few weeks, I called the Bishop to make an appointment to meet with him. He told me to go back to the original priest, who would sign my declaration of apostasy. I returned to the local rectory and met a priest of Chinese descent. He was very warm and accommodating. He explained how he understood the Hindu concept of ethical conversion. He signed my declaration and wished me the best.§

The next few weeks were extremely magical, as I had my nāmakaraṇa saṁskāra at Kauai Aadheenam on December 25, 1982, with my two-year-old daughter, Neesha, and an old family friend, Nilima Visakan, now Nilima Srikantha. Then we were off for six weeks of Innersearch with Gurudeva and forty pilgrims, visiting temples and ashrams throughout Malaysia, Sri Lanka (Yogaswami’s shrine was a personal highlight) and Tamil Nadu, India. It was a fantastic spiritual experience that continues to reverberate in my mind today.§

At the time, my husband was not a Hindu, but our three daughters were given Hindu first names at birth, while keeping his family name. We raised the children according to Hindu Dharma and Gurudeva’s guidance. In 1984 we moved to the Seattle area. During the ten years we lived in Seattle, my children and I gathered with the other local Śaiva Siddhānta Church members for weekly satsaṅga. We also met with the local Hindu community for festivals. We studied Bhārata Nātyam and Carnatic vocal music. We had open house at our home for local Hindus to learn more about Gurudeva’s teachings. My children attended the summer camps put on by Church members in Hawaii, and we stayed in the flow of Gurudeva’s mind even though we lived far from the other communities of Church members.§

All through these years, I prayed that my husband would become a Śaivite Hindu and accept Gurudeva as his satguru. With my husband’s permission, I would write the same prayer weekly, and during our weekly homa I would burn the prayers, asking the devas to please help our family to worship together and to live in closer harmony with Gurudeva’s teachings.§

In 1993 my husband formally adopted Śaivism, legally changed his name from Victor Dean Pontius to Durvasa Alahan. He became a vegetarian, stopped smoking and gave up catch-and-release fishing, which was his favorite hobby. He had his nāmakaraṇa saṁskāra on Mahāśivarātri in Kauai in 1994 and became a member of Gurudeva’s Śaiva Siddhānta Church. That fall we moved to the island of Kauai to live near the holy feet of our beloved Gurudeva.§

In November, 1996, my husband and eldest daughter went on pilgrimage with Gurudeva to India for a month. My daughter was interested in studying Bhārata Nātyam, and my husband, under Gurudeva’s guidance, left my daughter in India so that she could attend Kalakshetra College of Fine Arts and get a diploma in Bhārata Nātyam. She started college in June of 1997, and the rest of the family, my husband, myself and two younger daughters, moved to Chennai, Tamil Nadu, in November of 1997. The past three years have had their moments of difficulty, but overall they have been a peak experience of my life, a fulfillment of my heart’s desires. I am now looking forward in the spring of 2000, following my daughter’s graduation from Kalakshetra, to moving back to Kauai with my family and joining the other families there. Jai Gurudeva, Sivaya Subramuniyaswaminatha! §

Isani Alahan, 46, has for the past three years lived in Chennai, India, where she works in the home, cooking South Indian āyurvedic meals for her family of five and does home-school with her youngest daughter. She is also studying Carnatic music, Sanskrit, haṭha yoga and the Kerala health system known as Kalaripayattu.§

My Husband and I and Our Lifelong Quest

From Vietnam to Yoga; Austerity in British Columbia to a Fulfilling Life in Family Dharma. By Amala Seyon.

My first introduction to Hinduism was when I met my husband. He had been going through a very soul-searching time, asking God why the Vietnam war, why the rioting in the streets of America, and what does materialism have to offer the soul? While going through this trying time and praying, he took a world religion class at the university. One day a born Hindu man came to his class and talked about the Hindu religion. All the concepts of Hinduism were the truths my husband was looking for. This Hindu man had a meditation center and invited anyone in the class to come. My husband started going on a regular basis. §

During this time my husband asked me to marry him. He explained to me about the Hindu religion and took me to the meditation center. I was so happy to hear some of the concepts, like God is within you, the law of karma, the evolution of the soul. I felt like I had been in a cage, like a bird, and someone opened the door, and I was able to fly into something much bigger and deeper. §

My husband told me that if we got married this was the path he wanted us to take. I accepted that and supported it fully. This started the process, to our surprise, of a confrontation of Western and Eastern philosophies. Our first encounter was in finding someone to marry us. We wanted to have a religious blessing, and so my husband went to the Hindu meditation center and asked this saintly man if he could marry us. He explained that his visa did not allow him to perform the ceremony. So we went to my family’s Christian minister and asked him to marry us. He asked us to meet with him as he did with all young couples wishing to marry.§

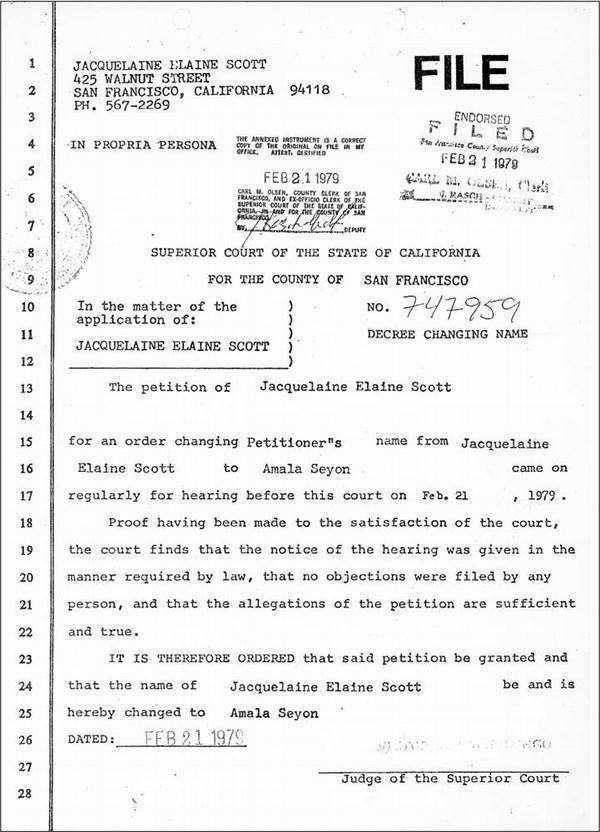

Amala Seyon’s decree of name-change, state of California.§

During this meeting he asked my husband a series of questions. Do you believe Jesus Christ is the only Son of God? Do you believe that the Holy Bible is the only word of God? The questioning went on for some time, and at the end of the interview he told my husband that not only could he not marry us but he was going to call my parents and tell them that he was against having me marry someone who was not a Christian. My minister went on to say that he couldn’t marry us because he didn’t believe in marrying couples from different religious beliefs. §

We then had to confront my mother, who was very much a Christian. This was all emotionally hard for her because of the belief that you could only be saved through the belief in Jesus Christ. She was very disappointed, and the issue caused a major disruption in our family. Finally, they accepted our marriage, and my husband located his past minister, now a professor of world religions at the university close by, who agreed to marry us. This brought to the forefront our Hindu beliefs to our family and friends. It was puzzling at the time, because my husband’s spiritual teacher had told us that all religions are one. §

After our marriage, we started reading all we could on Hinduism. My husband mistakenly followed the statements in Hindu scripture that we now realize were intended for monks. We sold and gave away all our wedding gifts and went to live in very remote areas of British Columbia. He read from morning until night and sat by a river for hours on end, but we finally realized we were not making real spiritual progress, and I was lonely living in remote areas and even on a deserted island. §

We started searching and praying, and one day someone invited us to meet our Gurudeva, Sivaya Subramuniyaswami. We recognized what a great soul he was immediately, and we started our studies with him. We had two daughters at the time, but had not had our name-giving sacrament into the religion as yet. So, when our children were five and three years old, we all had our name-giving together, formally entering the Śaivite Hindu religion.§

Gurudeva was very patient with us and helped my husband and me understand the dharma of family people and the limitless depths of the Hindu faith. My children were raised in the Hindu religion, and we spent a lot of years living near a Hindu temple, learning the culture and mixing with born Hindus at the Flushing, New York, Gaṇeśa temple. We learned so much and felt so naturally a part of the Hindu heritage. We followed a home school curriculum and taught our children in the home until they were twelve years old. We felt it important to get the Hindu convictions in strong, so they would know their religion. Our daughters are now both married and are wonderful mothers who stay home and care for their children. Our oldest daughter is married to a wonderful Hindu man from Mauritius in an extended family that showers her with love. We now live on the little island of Kauai and serve the community and the broader Hindu family through our many activities, all guided by Gurudeva himself. We are so very grateful to our guru. Aum Namaḥ Śivāya. §

Amala Seyon, 51, entered Hinduism in May 1975. A homemaker on Kauai, she and her husband live within walking distance of the Kadavul Hindu Temple.§

I’m So Proud to Be a Śaivite

Disillusioned with Catholicism, I Wound Up with No Faith at All, Then Discovered a Whole New Way of Perceiving Life and Beyond. By Asha Alahan.

It all seems like lifetimes ago. I had been raised in a Catholic family. My mother was a devout Catholic, my father had converted to Catholicism right before they were married. I was a happy child, believing in God, loving God and just doing as I was told. But when I reached my teens, I started to question many of the beliefs and became very disillusioned with the Catholic Church. So I left and became nothing!§

At eighteen I moved away from my parents’ home to live with my older sister in Santa Barbara, California. I loved God and knew that something was really missing, but did not quite know where to begin searching. My subconscious was so programmed that it was the Catholic Church or nothing. As children we were not even allowed to enter other places of worship; it was considered a sin. So I just did nothing! It wasn’t until I was twenty-one that I knew my life was on a down-hill spiral and I had to do something. I returned to my parents’ home and tried going to the local Catholic Church again. But I still felt that their religion did not hold the answers for me.§

It was not long after that I was married to my wonderful husband, and he introduced me to Gurudeva’s teachings. He showed me the “On the Path” book series and I listened to the original Master Course tapes that he had. It was all so new and exciting. The words were so true, and Gurudeva’s voice was so penetrating. It was a whole new way of perceiving the world and beyond—almost a little scary, as my subconscious mind kept trying to remind me of all the previous programming from early childhood and the Catholic school I had attended.§

Finally, we were able through an invitation from Gurudeva to come to Kauai for Satguru Pūrṇimā. I was about seven months’ pregnant with our first child. When I saw Gurudeva I was so surprised at what a tall person he was, with his white, flowing hair. His darśana was so powerful, I was almost overwhelmed. I had never been in the presence of such a refined soul. This was all so new to me.§

We continued our studies and finally came to a point where we were able to give Gurudeva three choices for our new Śaivite Hindu names. After receiving our new names, we went to tell our parents about this. Both sets of parents lived in the surrounding area, and we saw them often, so even though this was new (our name change), it wasn’t a surprise. But they did take a while to adjust. It was interesting that it was my father who first started to call me by my new name, and it wasn’t long after that my mother did also.§

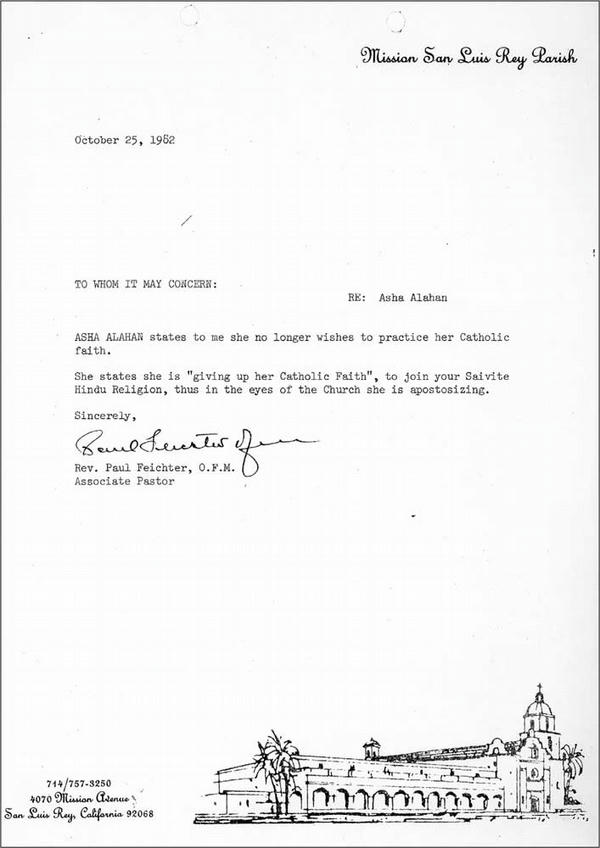

Asha Alahan’s severance letter from her Catholic church.§

We continued our studies with Gurudeva and proceeded to follow the steps towards severance. I had been confirmed in the Catholic Church so I needed to go back to the original parish where this had taken place and talk to the priest, have him understand my position and ask if he would please write a letter of severance for me. By the time I had finished speaking with him, he was unsure on what to say to me. He denied me the letter and suggested that I speak with the Archbishop of that diocese. I called and made an appointment with this person. I felt since I was going to a higher authority than the local priest that this should be easier. I was wrong. I thought he might understand my position and agree to write a letter for me. I was wrong. Well, he was not at all happy (even on the verge of anger) and totally refused to let me explain myself. So I left, wondering where I might go next.§

In the area where we lived there were some old California missions that were still functional (as places of worship) so I decided to speak with a priest at the nearby mission. I knew the moment I walked into this priest’s office that I had been guided by divine beings—he was the one to speak with. He had symbols of the major world religions hanging on his walls. We spoke for a while, and then he wrote me a letter (p. 37) stating that he understood that I wished to sever all previous ties with the Catholic Church and would soon be entering the Hindu religion and then wished me well.§

Gurudeva suggested that I come to Kauai’s Kadavul Hindu Temple to have my nāmakaraṇa saṁskāra. Which I did. It was a magical saṁskāra. At the time I don’t think I realized the deep profoundness of that experience, finally finding the place where my soul knew it belonged.§

I am so proud to be a Śaivite Hindu. I am proud of my Hindu name and often get compliments from people who hear it for the first time. §

I am grateful and appreciate all that Gurudeva has done for me all these years, guiding me gently and offering me opportunities to make changes on the outside as well as on the inside. Jai Gurudeva. Jai!§

Asha Alahan, 44, lives in the San Francisco East Bay, California. She formally entered Śaivism in 1985 at Kauai Hindu Temple. Asha, whose husband and children are also Hindus, is a wife, mother and housewife and a home-school teacher to all her children.§

Excommunication and Facing the Family

The Priest Tested My Mettle, and My Parents Accepted My Decisions. By Kriya Haran.

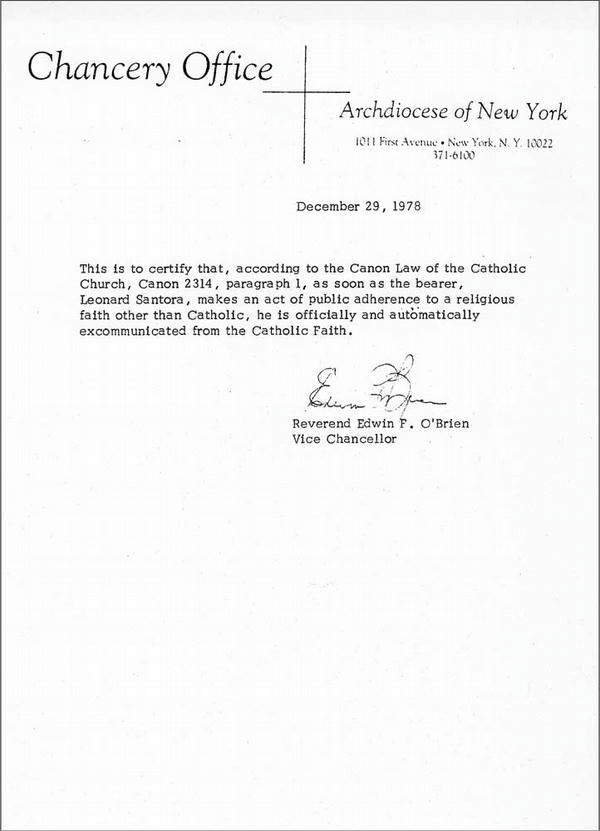

I was born in New York City of a very strong Roman Catholic background. I went to church regularly. I was also an altar boy for a while. I made my communion and confirmation in the neighborhood church. I went to Catholic school for seventh and eighth grade, and my brother went into a monastery for a short time. I was formally excommunicated from the Catholic Church in 1978. I was lucky, as I was in New York City at the time, worshiping at the Gaṇeśa Temple in Queens. §

I remember a few difficult parts of my excommunication. I think I was really coming to terms with my religious beliefs at that time. I was studying intensely with Gurudeva and one must have that total commitment and faith in your beliefs in Hinduism, because when you get excommunicated and are not of any religion it is a scary feeling. You realize how important religion is in one’s life. §

Kriya Haran’s letter of excommunication.§

Facing my family was difficult and emotional. I didn’t know how they would react to my decision. Also, I was worried about how they would react to my name change. Surprisingly, they accepted my decision with no arguments. They saw how much I had changed for the better since my association with Gurudeva, the swāmīs and other monks of Śaiva Siddhānta Church. §

The other scary event I experienced was going to the archdiocese of New York City and facing the intimidating priests and nuns. I had to do this in order to get excommunicated. They simply do not want to let you go. They make excommunication an uncomfortable experience. I was (and still am) so sure of my Hindu beliefs that I would not take “no” for an answer, especially when the priest put his feet up on the desk and lit up a cigarette. The priest and I got into a heated discussion about Catholicism, Hinduism, heaven and hell, but my convictions and ties to Gurudeva were too strong for the priest. In the end, I succeeded in getting excommunicated (letter, p. 40).§

Kriya Haran, 57, lives in Seattle, Washington, where he owns and operates his own taxi cab. He became a Hindu on January 4,1979.§

Reconciliation Was Arduous

I Had Been a Catholic, Mormon, Buddhist, New Age Person and More. By Damara Shanmugan.

In 1989 a friend and manager of a metaphysical bookstore gave me a little booklet as a thank you gift. She said, “It is by an American master known as Gurudeva.” I read I’m Alright, Right Now every night for one month before going to sleep. Deep inside I knew that every word it contained was “the Truth,” not just someone’s interpretation of the Truth.§

At the end of 1989 I sent away for The Master Course by mail and became a correspondence student of the Himālayan Academy. At this time in my life I was very active in the New Age movement. I worked full time and was also a massage therapist and rebirther. For years I had been going from teacher to teacher. All of them without exception taught, “Be your own guru, a real one is unnecessary,” and “religion is what is wrong with the world.” For almost one year, I studied from afar, being careful not to get too close to this strangely familiar Hindu world.§

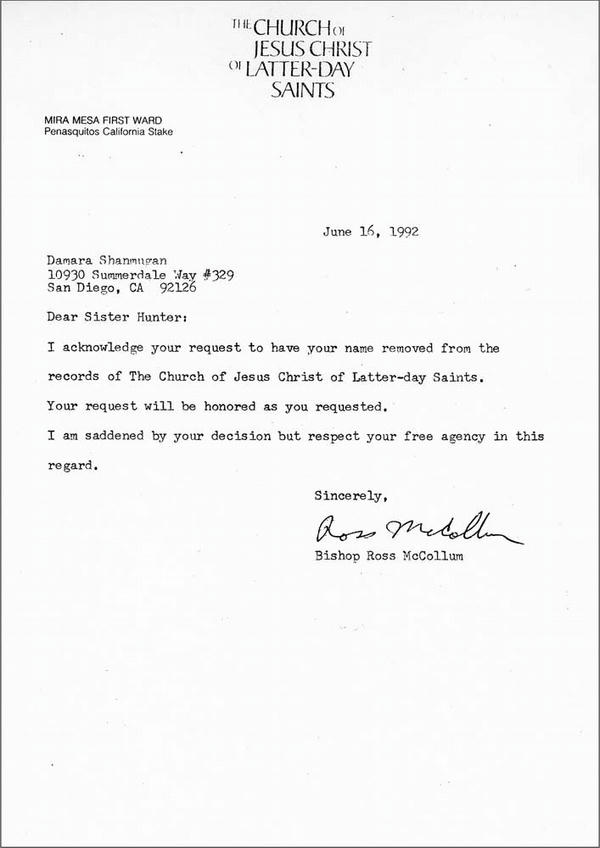

Damara Shanmugan’s letter from her Mormon church.§

I first met with Gurudeva in person on October 4, 1990. Any plans I had to only dangle my toes in the warm waters of Hinduism completely dissolved on that day. Just simply sitting in the presence of this wonderful enlightened being caused a shift within me that I could both feel and understand. I was forty-four years old at that time. I began to do pūjā every day as best I could and continued to study The Master Course teachings by mail and in seminars.§

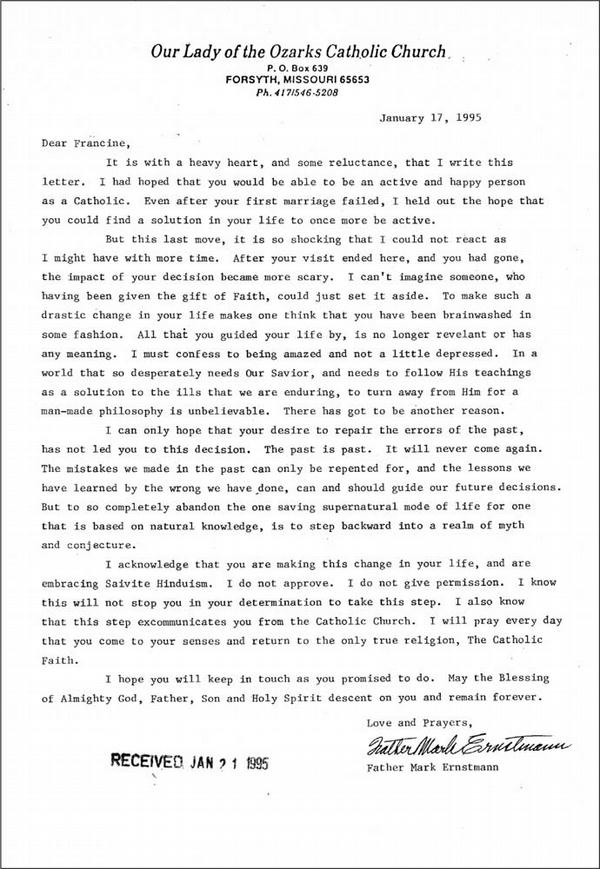

Unbelievably, I was moving toward membership in the only Hindu church on planet Earth. I probably hold the record for the most religions severed from! I had been born and raised a Catholic, attending ten years of Catholic school until 1960. In 1981 I became a Mormon and was very active as both a Ward and Stake Relief Society cooking teacher. By 1985 I found myself practicing Zen Buddhism and exploring the New Age movement. By nature, I do not have a very confronting personality, and over the years I had just drifted from one thing to another.§

By December, 1991, I had completed all the necessary study to move toward becoming a Hindu. The next step was to reconcile what I now believed as a person aspiring to become a Hindu against all the beliefs I had held in the past. I took a whole month of vacation from work and spent that entire time searching my heart and soul, reconciling each belief as a Catholic, Mormon, Buddhist, New Age person and, yes, I even absorbed some beliefs from the drug culture and secular humanism.§

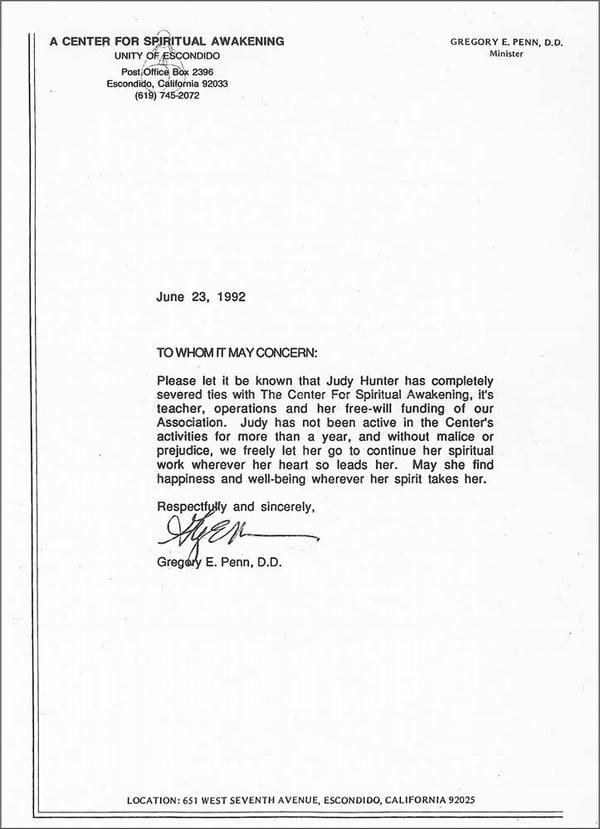

Damara Shanmugan’s letter from her Buddhist teacher.§

I wrote over three-hundred pages of confessional prayers during that month. During this “gut-wrenching” time I had terrible pains in my stomach and more than a few times came very close to asking to be taken to the hospital. Why would I put myself through this? Was there some outside force making me do it? For the very first time in my life I knew from the inside out that I was finally on the right path for me.§

My family did not take the change very well, and yet they all had to admit that I was happier and more content than they had ever seen me before. They decided to tolerate the changes. On January 1, 1992, I was given my new name, Damara Shanmugan. Such a beautiful and unique name. Damara means outstanding and surprising, an assistant of God Śiva. Shanmugan literally means, “six-faced,” one of the many beautiful names of Lord Murugan, the God of Yoga.§

Now began the formidable tasks of legally changing my name and obtaining a letter of severance from all former religious affiliations. But I was no longer just a drifter. A new-found courage was born of the knowing, without a shadow of a doubt, exactly what I believed from the inside out—not the outside in. I visited the Social Security Office, Department of Motor Vehicles, payroll department of my employer and filed a petition with the county of San Diego for a future court date in August of 1992. Every bill, card, account and license had to be corrected. Each phone call required an explanation, “Just as Cassius Clay became Muhammad Ali....”§

I went back to the Catholic Church that I had attended until nineteen years old. As I attended mass each Sunday for a couple of months, I recognized the comfortable and soft feelings of this huge church. I realized that I had been guided and nurtured by kind, inner plane beings, angels, all through my childhood. I understood that there is no competition for souls in the inner worlds. And yet I also knew that what they were preaching I no longer believed.§

I was bounced back and forth between the diocese and the parish when I called to get an appointment for excommunication. Finally one day when I was in the neighborhood, I just stopped by the rectory and asked to see the priest. They showed me in, and I told my story of wanting to be a Hindu and needing a letter of severance to move along my spiritual path. The forthcoming letter was beautiful, kind and loving beyond my wildest hopes and dreams. I understood the wisdom of closing this door with love and understanding.§

When I went back to the Mormon ward I had attended for three years, I had a similar experience. The official letter of severance (p. 42) took months to arrive from Salt Lake City. And they sent many people to my home during that time to try to get me to change my mind. I discovered that I possessed an unwavering certainty within. This was a great surprise, for I had never been aware of this part of my character before.§

Finally, I visited my New Age teacher, who loved and practiced Zen Buddhism. I could literally feel the deep karmic issues between us dissolving away. Another kind and loving letter was forthcoming (p. 44). My stomach was totally at peace now. Wow, I had done it! Not bad for a non-confrontational person like myself.§

I made plans to travel back to the Garden Isle of Kauai for my nāmakaraṇa saṁskāra. Just before leaving I had an incredible experience. One evening while sitting on the couch fully awake, I had a vision that is clearer today than it was on that night. I was surrounded by all the guardian angels who had helped me as a Christian. There were thirty or forty beautiful beings all around me. They were celebrating my becoming a Hindu! All around us was great celebration and joy. Then, off to the left, appeared another group of beautiful beings. I was lovingly escorted over to the new group, and I moved over to join them. I knew these to be my new guides, devas and Mahādevas of Hinduism. There was genuine celebration and pure joy among all these inner plane beings—no competition, no sorrow. I can still feel the love and well wishes of the former group. §

The official ceremony took place in July of 1992, in the small monastic Kadavul Temple on Gurudeva’s paradise property in Kauai. There was a blazing fire in the homa pit and I was asked to stand between the Earthkeeper crystal and the six-foot-tall Śiva Naṭarāja during the last part of the ceremony. I don’t remember my feet touching the ground. Gurudeva gave me a small damaru, Śiva’s drum, symbolizing creation. I felt like a brand new person—new name, new religion, new culture, new way of dressing, new way of acting and a totally new way of seeing and relating to the world and people around me. It was an awesome day, and the feelings are stronger now than they were then.§

Hinduism cannot be forced upon someone. Rather, Hinduism is found from the inside. Hinduism is a yearning vibration that can only be satisfied by finding and practicing Sanātana Dharma, the Eternal Truth. For me, Hinduism is none other than my own integrity, ever urging me on. On November 1, 1992, I became a member of Śaiva Siddhānta Church. I continue to make changes on the outside to match the unfolding truth and beauty from within. §

Damara Shanmugan, 53, lives in La Mesa California with her 80-year-old mother. She became a Hindu on July 12, 1992. Damara is the Founder of The SHIVA (Saivite Hindu Information for the Visually Assisted) Braille Foundation. She has also been teaching haṭha yoga in the San Diego area since 1993.§

From the Masonic Order and Roman Catholicism

How Our Quiet Life in Alaska Was Turned Inside Out When We Vacationed to Hawaii. By Shyamadeva and Peshanidevi Dandapani.

In February of 1994 we decided to take a relaxing vacation somewhere in the warm sunshine without a busy sightseeing schedule. Kauai presented itself in a roundabout way, and since we had visited Hawaii before (although not Kauai) it seemed to meet our needs. The roundabout got us to Kapaa, where we stayed at the Islander on the Beach. §

Three days into our vacation we went into the Lazarus Used Bookstore, where Peshanidevi, my wife, began collecting books. She soon handed me a pile to purchase. On top was a copy of the second edition of Dancing with Śiva. I picked it up and looked at it, and on the back was a short biography and picture of the author, Satguru Sivaya Subramuniyaswami. Upon reading it, I said to my wife, “This author is right here on Kauai, and there is a temple here.” We bought our books and went back to the hotel.§

At this point we both seemed to be totally compelled, propelled and impelled to locate Gurudeva and the temple. We found a listing for Subramuniyaswami, Satguru Sivaya, in the local phone directory. There was also a phone listing for his Daily Sermonettes. We called, but there was no answer at the first number, so we called the Daily Sermonettes number and received darśana from Gurudeva for the very first time. After a few more attempts, Peshanidevi was able to talk with Yogi Rishinatha. She explained that we had found a copy of Gurudeva’s book in the bookstore and would like to come to the temple and asked what the proper protocols were for visiting the temple. He gave instructions on what sections to read and directions for coming to the temple the next morning at 9:00 for pūjā.§

We were both very excited the next morning as we drove up Kuamoo Road. With our Safeway flower bouquet in hand, we made our first walk up the path to the temple. Seeing the 16-ton black granite Nandi and the temple for the very first time was breathtaking. We washed our feet and entered the temple. It was beyond words. It was as if we had finally arrived back home after a long and arduous journey. Yogi very graciously welcomed us and guided us through the protocols, including prostrations to God and Gods. We sat down, the only two people in the temple that morning, as Ceyonswami began the pūjā. We did not know Sanskrit but somehow seemed to intuit the deeper beauty and meaning of the pūjā. Afterwards, we bought the newest edition of Dancing with Śiva and Living with Śiva. We purchased one of the tri-folds of Lord Gaṇeśa, Lord Murugan and Lord Śiva, plus postcards of the Deities, pamphlets and incense. We felt so alive that it was difficult to leave such an awesome experience and place. §

Upon arriving back at the room, we made a small shrine with our pictures and flowers and began reading. The next day we returned to the temple. And this time, after the pūjā Ceyonswami came out to talk with us. It was so incredible to be in his presence. He was so loving, gentle and kind. We told him about finding Gurudeva’s book and how we came to the temple. He explained some about Vedic astrology and asked if we would like to have our astrology done. We said, “Yes” and gave him our birth data. He said he would have it for us the next day. Again, we left dragging our feet, not wanting to leave the temple.§

After the pūjā the next day, Swami asked us if we would like to meet Gurudeva. Yes, of course! When? Wait here. We can remember feeling His loving energy before he walked through the curtain. We could feel the love. And then we fully prostrated to our beloved Gurudeva for the very first time. It was as if we had done it many, many times before. As he sat down in his chair, he looked at us and said, “I see you are dancing with Śiva.” At that moment we knew we had found our Guru, our Precious Preceptor, our Teacher. At that moment our lives were forever changed.§

Later Ceyonswami gave us our astrology and explained some of it to us. He also talked about becoming vegetarian, which we were not. He gave us a wonderful little pamphlet entitled, “How to Win an Argument with a Meat-Eater.” Unbeknownst to us, we had just become vegetarians. Our vacation had turned into a pilgrimage (in fact, it was the last vacation we have taken) and we had come back home to the Sanātana Dharma, the religion of our souls. During our two-week stay on Kauai, we received Gurudeva’s darśana three times. Each time we were amazed at the power and how much we enjoyed it.§

We left the island, full of both sadness and joy, and went home to Alaska. We set up a small shrine and every time we sat in the darśana of God, Gods and guru, we longed to return to Kauai and stay forever. We wanted to renounce the world to serve God and guru. That was not possible, but we did begin our first sādhanas in Himālayan Academy. In June we took our first three vrātas. §

We pilgrimaged back to Kauai in November of 1994 for Kṛittika Dīpam. We stayed with the Katir family in their bed and breakfast, and we really increased our learning curve. We met and began merging with the island Church families. This was another special homecoming and a magical time with Gurudeva. During this pilgrimage, we truly began to embrace the Sanātana Dharma and returned home to Alaska with more sādhanas, to talk to our family and friends about becoming Hindus, and to begin merging with the Hindu community in Anchorage. For the most part everyone was tolerant of our enthusiasm about becoming Hindus, but no one wanted more information.§

We had already leased out our house in preparation for moving to Kauai, so we rented an apartment and continued our studies and began the conversion and severance process with the most patient of kulapatis! Kulapati Deva Seyon gently nurtured us through this most intense time. It was our in-depth study to review our lives, to determine our true beliefs, where they came from and if they were still valid for us. There were many rewrites and surprises. We returned to our previous influences (myself to the Freemasons, and Peshanidevi to the Catholic Church), studying and participating with them again to be positive that we wanted to change our path. It was difficult to go back, because it did seem we were regressing. However, we knew that we were building a solid foundation on which to begin our new journey.§

We returned to Kauai for the Pañcha Silanyāsa Stone Laying ceremony in April of 1995. It was an incredible pilgrimage. To be back on Kauai, at the holy feet of our beloved satguru and at this most auspicious time in the evolution and manifestation of Iraivan Temple, was such a remarkable and life-changing time. We met and merged with more of Gurudeva’s global Church family, and we received our Hindu names, Shyamadeva Dandapani and Peshanidevi Dandapani. Such beautiful and long names! Gurudeva instructed us to legally change our names and to sever from our former religions by going back and fully embracing our former beliefs and writing a point-counterpoint for each one of them.§

I returned to the Masonic Lodge and fully embraced Freemasonry for the next thirty days. I attended the lodge and participated fully in all its ceremonies and rituals. Everyone was glad to see me return, as it had been a few years since I had last attended lodge. At the end of the thirty days, I was completely convinced that I no longer held the inherent beliefs of the Masonic Order. Even with all the years of being a very active Mason—and my father also being a very well-known Mason—I knew it was neither my belief nor my path. The Masons say, “Once a Mason, always a Mason.” The only way to sever the vows was to become a self-imposed apostate. I prepared a letter declaring that I was a self-imposed apostate to the Masonic vows and beliefs, and that I was converting fully to Śaivite Hinduism. I read the following letter in open lodge before all the members present and a copy was given to the secretary to be recorded into the minutes of the meeting on June 8, 1995, at Kenai Lodge No. 11. §

To: The Worshipful Master, Wardens, Officers and Members of Kenai Lodge No. 11§

“I am here to terminate my Masonic membership as a self-imposed apostate. Apostasy means “an abandoning of what one has believed in, as a faith, cause, principles, etc.” I am abandoning, and I have already abandoned, my former Masonic, Biblical and Christian beliefs. I do this of my own free will and accord and with a full understanding of the principles, landmarks, tenets and beliefs of Freemasonry. I also realize that taking this step will terminate my membership in all Masonic concordant bodies. My decision is made with the application of the strictest ethical principles of honesty and integrity. It is why I have chosen to do this in person at a stated communication of this Lodge. This is a personal decision. It is the spiritual path I have chosen to live. If I did not do this, I firmly believe it would affect my spiritual unfoldment as a Hindu. ¶I accept the finality of my decision. I would expect from this day forward to no longer have any privileges as a Mason. I have made my decision and will live by it. In fact, my decision to become a Śaivite Hindu includes adopting a Hindu name. Yesterday the Kenai Superior Court approved my legal name change to my new Hindu name, Shyamadeva Dandapani. It will be official in approximately thirty days. ¶In closing, I want each of you to know that this is my sole decision. It does not nor should it ever reflect on any member of my family or any member of this Lodge. I also want you to know that I acknowledge all the goodness that your friendship has brought into my life over the years. I am thankful to each and every one of you, for it has helped guide me on my path as a seeker of the Truth. I sincerely wish each and every one of you the very best that this life has to offer.”§

The only question came from the secretary, who asked, “Are you sure you do not want a demit?” to which I replied, “I am sure.” I remained until the Lodge closed. Afterwards, a number of the members came up and wished me well on my path. I felt a great sense of relief and release. §

Peshanidevi’s heartfelt letter from her Catholic priest.§

Peshanidevi returned to the Midwest to attend mass and meet with the priest who had given her instructions for being baptized a Catholic. He had continued as a personal friend for some thirty years, even though she had not practiced that religion since her divorce in 1971. Two hours of discussion did not produce a letter of release, because he said, “Once a Catholic, always a Catholic.” He took it very personally but promised a letter to follow. A month later it arrived (p. 54). The fire was strong but the bond was broken. §

We applied for our legal name change and announced it in the newspapers. We made our court appearance, and the judge asked why we were doing it and if there was anyone in the court that objected. We told him for religious conversion to Hinduism, and no one objected. The whole process took less than five minutes and would become effective in thirty days. Gurudeva then blessed us with the news that we would have our nāmakaraṇa saṁskāra at Satguru Pūrṇimā. We were overwhelmed with his love and blessing.§

On the auspicious day of July 9, 1995, in Kadavul Hindu Temple we made the irrevocable step of having our nāmakaraṇa saṁskāra. We felt the blessings of Lord Śiva and Gurudeva pour forth on us as we sat before God, Gods and Gurudeva and took this momentous, life-changing step onto the perfect path back to the lotus feet of our loving Lord Śiva. We “declared of our own volition acceptance of the principles of the Sanātana Dharma, and having severed all previous non-Hindu religious affiliations, attachments and commitments, hereby humbly petition entrance in the Śaivite Hindu religion through the traditional nāmakaraṇa saṁskāra and plead for recognition of this irrevocable conversion to Śaivite Hinduism.” Thank you, Śiva! Thank you, Gurudeva! We had come home to the religion of our souls. We experienced so much love, joy and emotion during the nāmakaraṇa saṁskāra. And it affirmed our beliefs that we are Śaivite souls and that we had been with Gurudeva in previous lives.§