CHAPTER 9: BE FRIENDS WITH GANESHA§

My Month of Doubt§

Ganesha has been in my thoughts ever since I can remember, when my parents took me to the temple as a baby. My first religious experiences were the sounds, sights and smells of that holy place. Watching the elephant-headed God, praying to Him, singing songs to please Him—through the years I took these important parts of my life for granted.§

For a while last year, my friend Jennifer changed that. I was fifteen and in ninth grade. Everyone says friends can have a strong effect on you at that age, and I suppose they are right. My closest friend, Erin, had come to my house often, and I to hers. She had never made an issue of the big picture of Ganesha in my bedroom; she just said, “What a beautiful picture, Parvati! Why does he have an elephant head?” §

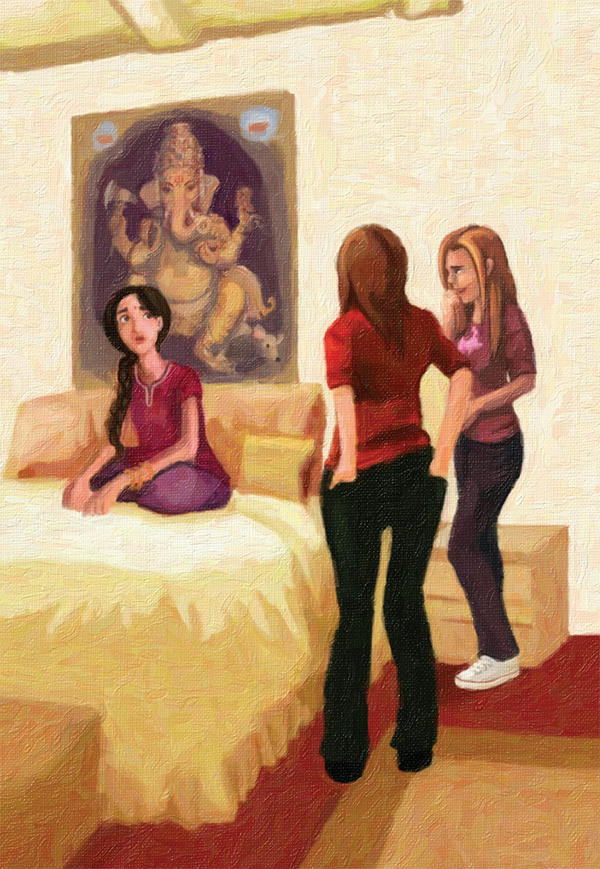

One Saturday when Erin was over, Jennifer and her friend Samantha came by for some games and TV. When we got to my bedroom, Jennifer took one look at Ganesha and let loose with, “What is that strange-looking creature! Some kind of Hindu beast?” She and Samantha burst out laughing. §

Trying to explain only made it worse. I spoke in my softest tone in a way I hoped she might understand, “Ganesha is the God we always pray to first, because He can remove obstacles to what we want to achieve. For example, He can free up time for studying, so we can get good grades at school.” §

“Sounds about as believable as writing to Santa Claus to get something for Christmas! At least with Santa Claus your parents will probably read the letter and might actually get you what you want, but this elephant’s nothing but a painting, something people think up for children.” §

Erin nudged me to move out of the bedroom. The four of us went downstairs to watch TV, but you could have cut the tension with a knife. If my Dad had been there, he would have asked the two of them to leave. After they finally did go, Erin reminded me it was just one person’s opinion, and you should always consider the source of any opinion. I loved her for trying, but she wasn’t Hindu. She understood in some sort of polite universalist way, but she didn’t really understand. Ganesha was just as real to me as Mom or Dad. I was glad I hadn’t shown them the shrine room. I can’t imagine how mean Jennifer might have been in there!§

Erin told me Jennifer’s parents were atheists who took pride in demeaning religious people and actually coached their daughter on how to do it. They hated religion and taught her to feel the same way—and, I just learned, to act on those feelings. She was just as quick to insult her Christian friends. That night, Dad explained to me that not all atheists are like that—the word just means someone who doesn’t believe in God, not someone who is consciously critical of those who do.§

The next day at school, Jennifer spread the word that I was some sort of devil worshiper, which was apparently worse than being a hardened criminal. Some of the kids stared at me when I walked by. I heard mocking snorts and some really bad fake elephant roars, but none of them had the courage to look me in the eye. Fortunately, I had Erin and a bunch of other friends who knew me. Plus, most of the Christian kids in the school took my side—partly because they believed I should be able to practice any religion I chose, but mostly because they had been on the receiving end of Jennifer’s attacks themselves. It was one thing for Jennifer to ridicule dozens of well-connected Christians, quite another for her to go after the school’s lone Hindu, so they sided with me. I was happy to have their support.§

It was an incredibly difficult time for me. Besides the snide snickers from kids I once counted as friends, the whole episode planted seeds of doubt. What if Jennifer was right in some way, even if she was rude? I had seen rude people be right before, and really polite people be dead wrong. Perhaps it was more likely rude people were wrong, but the rude kids who spoke before being acknowledged by teachers often did have the right answers. Things became uncomfortably fuzzy. Ganesha was really fuzzy. Was He real—or was He just some vague concept, something I believed in only because my parents taught me to? §

That night I stared at my Ganesha picture and decided to take it down. I rolled it up and put it in the closet. For the next few weeks of my life that’s all He was—a stored-away picture. It reminded me of Mom and Dad’s photo albums of ancestors I had never met—old pictures that had no meaning to me. Mom and Dad could look at them and tell stories of how they traveled to Pillaiyarpatti Temple when they were young. Meaningful stories—for them. I wondered if I would ever want to go to Pillaiyarpatti, or even to our local temple again. If Ganesha was just a meaningless myth, as Jennifer asserted, then what was all this fuss about? Why not just get on with life? A part of me deep inside knew that wasn’t true, but heavy doubt clouded that knowledge. The kids around me in America all seemed to be doing just fine without Ganesha. §

About two weeks later, on a Saturday, Mom told me we were going to temple the next day. It was a long drive, so we only went every other weekend. For the first time in my life, I declined, “I think I’ll stay back this time.”§

Mom’s expression reminded me of the day her brother called from Hyderabad saying they had just lost Indira Auntie—sad, shocked and confused. She didn’t know what to say.§

The next morning she and Dad drove off without me. I was glad they hadn’t pressured me, and we hadn’t argued about it. All Dad said was, “Yes, Parvati, maybe you just need a break from temple. It’s okay.” I loved and respected that about them. They allowed me to figure out some stuff on my own.§

The minute they were out the door, I felt lonely, like a solitary Himalayan sadhu in a big, silent house. If nothing else, I could usually hear Mom making some sort of noise in the background: singing to herself in the kitchen, doing laundry or relaxing in front of the TV. I had heard the saying that a home is where the mother is, and it hit me how true that saying is. After an hour or so of total boredom, I vowed I would go to temple next time—if not for Ganesha, at least for the people, at least for my parents. §

My homework all complete, I went to the shrine room to ponder His existence. Not just His, but Siva’s and the other Gods as well. It didn’t help much. Doubt was like a snowball on a hill. Once started, it had a building momentum of its own. My time of reflection was brief. §

Back upstairs, I decided to take another look at Ganesha’s rolled-up picture. But before I could get to it, I noticed something else: the fat-pig lucky charm my friend Xian had given me in sixth grade. Memories came rushing back. §

I was glad I had met Xian, a boy from China. He had been an interesting friend, that year and the next. Besides, his situation helped me realize how cultural differences can lead to misunderstandings that can lead to hard feelings—and difficult times, especially for the one being misunderstood. I could see parallels between Xian’s situation then and mine now.§

Nobody, including our teacher, Mrs. Davis, could pronounce Xian’s name. I only knew it as Xian because it was written on our class list that way. On the first day he tried several times to get us to say it correctly. But not even Mrs. Davis could do so, and she was incredibly patient and tried the hardest. The nearest I ever came was ‘Zhwon.’ Still Xian only smiled and said, “Close, Parvati.” The fact that he had learned to pronounce my name easily only made matters worse. By the end of the first week he became “Shawn,” a name we could all say. He looked sad and relieved at the same time about this logical but unfortunate solution to a clash of cultures. §

Mrs. Davis said we were lucky to have Xian in our class because he could add a lot to our understanding. I felt sorry he was getting picked on. He was shy and already under a lot of pressure just getting used to America. When someone called him an FOB, I had to ask Mom and Dad what it meant. “Fresh Off the Boat,” Dad translated. He laughed when I asked, “So, you and Mom were once FOBs too?”§

“Yes, Parvati, at one time we were. But it’s not a compliment, and we shouldn’t use it.” §

The biggest cultural clash hit Xian a lot harder when we studied China later in the year. On the subject of food, the textbook said the Chinese eat dogs. At that, several kids made loud, disgusted noises; others just looked shocked or outraged. Xian winced. §

Dog sounded disgusting to me, too—but so does cow, pig, chicken, fish and eggs. I have been vegetarian from birth, and the thought of eating any animal is not appealing in any way. It seemed hypocritical that these kids, who ate many kinds of meat, were so outraged about another culture’s fondness for dog meat. Of course, many had pet dogs, and eating your pet does sound worse than eating something from a tidy package bought at a store—something you don’t even associate with ever being alive. Some argued that dogs are smart, but pigs are smarter than dogs, and Americans have no problem at all with eating pork and bacon. Some people even eat dolphins, who may be even smarter than humans! §

It got even tougher for Xian when the class bully confronted him and asked whether he had ever eaten a dog. Unfortunately, Xian wasn’t used to the body language and other subtle posturing of bullying, so he proudly answered, “Yes, and snake, too.” §

Within the week most of the kids in school taunted him as some sort of snake-eating, dog-chewing monster from China. The meaner kids asked if he preferred poodles to dalmatians, rattlesnakes to boas. If it wasn’t for Mrs. Davis and the school counselor, and kids like David, Erin and me, I think he might have changed schools. Some days he looked like he wished he could get back on a plane and go home to China. But he persisted, as did I and many others who befriended him. Eventually the fuss died down and he became popular. But he never talked much about his ancestral home. §

At the end of the school year, Xian gave me this lucky pig ornament. Today it seemed like Ganesha was speaking through it: “It’s not that Jennifer or kids like her are intentionally mean. It’s more that a foreign culture frightens them, because they are insecure in their own ways.” §

Remembering what Xian had gone through helped a ton. His situation was far worse than mine, but he had the courage to soldier on. Still, having it happen personally is harsh. Thank goodness most Americans had grown beyond the more brutal and overt racism of earlier days.§

When I heard our car enter the garage, my mood shifted. I hoped they had brought some temple food, and they had. That always cheers me up!§

Two weeks later, Mom again announced a trip to the temple. I went with them this time. I had friends who would be there, and they were fun to be with. Besides, temple food is even better fresh. §

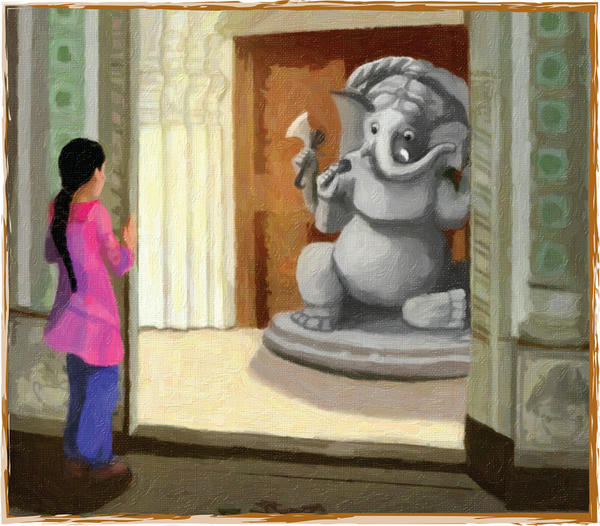

When we entered, I wasn’t sure if I wanted to walk with Mom on her pradakshina rounds, but she gave me her “Come along now” look I was so used to. It wasn’t like a bossy demand, just one of gentle encouragement. But I could sense her doubt, too. My doubt was about Ganesha, but hers was about me. §

Ours is a Siva temple primarily, but there are side sanctums for Ganesha and a few other Gods. The small Ganesha shrine is my favorite spot to sit. My parents and I had once discussed favorite spots. It seemed everybody had one in the temple, not just us. §

As we came around the corner to peek at Ganesha, the first part I saw was His left eye—and it seemed like He was looking right at me. Then as we walked further, I noticed a white woman dressed in a beautiful sari just like all the Indian ladies. She was blonde, like my “friend” Jennifer, who had insulted Ganesha. Her husband and small child were there, too. He prostrated full out before Ganesha, just like Dad did. The contrast between these people’s joy in worship and Jennifer’s negativity was striking. I already knew not all Westerners were like Jennifer, but I wondered what had brought these people to Hinduism. When we got near the Siva sanctum, I saw tears in the man’s eyes. “Wow!” I thought.§

After once around the temple, we each went to our private spot to wait for the main puja. Then we followed the priest for arati at each of the sanctums until the puja to Lord Siva was conducted. After taking the final flame, I headed downstairs for food. §

I took my plate to sit with my friends, wondering if any of them ever had doubts like I was having. Not knowing quite how to begin, I started with the topic of favorite places upstairs. “Thamby,” I asked, “have you ever noticed how everyone seems to have their favorite place to sit in the temple?” §

“Yes. I notice that sometimes, especially with certain people. You would think they owned certain pillars, no?”§

“What’s your favorite spot?” §

“It’s not a place I sit, it’s a place I walk. I get a nice positive feeling there.”§

“Where is that?” I asked.§

“Well, it’s kind of personal... But yeah, it’s just when you walk around the small Ganesha sanctum and peek in. It seems like Ganesha is looking at me right then.”§

My curiosity piqued now, I asked, “Which eye?”§

“It’s always the left eye. I don’t know why, but I get this feeling. I look at His right eye sometimes just to double check, but I don’t get the same feeling. Weird, isn’t it?” §

I had to smile. “It doesn’t sound weird to me!” §

When other friends joined the conversation, it turned out Thamby and I weren’t the only ones who felt certain parts of the temple were extra special. Some of the kids even had the same feeling about Ganesha’s left eye.§

The next week at the temple, I made a point of attending the Ganesha puja, partly to check out that eye thing again. This time, something really strange happened. The priest was chanting the 108 names of Ganesha, and Ganesha was chanting right along with the priest. I could see His mouth moving! I looked away and Ganesha stopped. Then I looked back and He started again. Finally, my mind accepted what I was seeing—and right then Ganesha winked at me! Gods with a sense of humor? Who would have thought? §

I went home in a daze not saying a word about all this to my parents. I thought they might think I was nuts, even though Dad had once told me about a vision of Murugan that changed his life. Plus, our Guruji said that when something spiritual happens to you it’s best to keep it to yourself; otherwise you may lose the divine energy of the experience. He said not everyone will have a dramatic vision, but Hinduism is a religion of experience, not blind faith. If we watch closely, we can catch even the little things the Gods do that let us know they are watching over us.§

That night I dreamed I was back in the temple, walking up to the Ganesha shrine. I could even smell the incense. When I got close, Ganesha looked straight at me, both eyes wide open, and demanded, “What am I doing in that closet?” §

Startled, I woke up, the image and words crystal clear in my mind. §

“Got the message,” I said to myself. I stood up, took His picture out of the closet and put it back up on the wall, all in the middle of the night. §

The next morning I asked Mom for one of her Ganesha statues. I put it right in the center of my dresser counter. Behind it I placed Xian’s gift. Its significance would remain secret, just like the visions. I had all the proof I needed that He really was there. Never again could anyone make me doubt Lord Ganesha’s existence.§

I know there will always be people who question my beliefs, and some things I will have to keep to myself. But now I am firm in what I believe. I’ll ask Ganesha to guide me in my daily situations and to help me remember who I truly am. §

The next time I’m with Jennifer her comments will be “in one ear and out the other.” Sure, I may react in the moment, but there’s no way it’ll take me a whole month to figure it out. §