Chapter Six

Muktiyananda Sails to Sri Lanka

Jaffna, which had once boasted its own king, was culturally and spiritually under siege. Over the past two centuries it had fallen under the successive dominion of a triumvirate—the Portuguese, the Dutch and the British. These bands of colonizers came to this idyllic island to extend their hegemony: political, business and religious. Many churches were built in and around Jaffna, and Hindu temples were destroyed in the process. The need for a spiritual leader was never greater. §

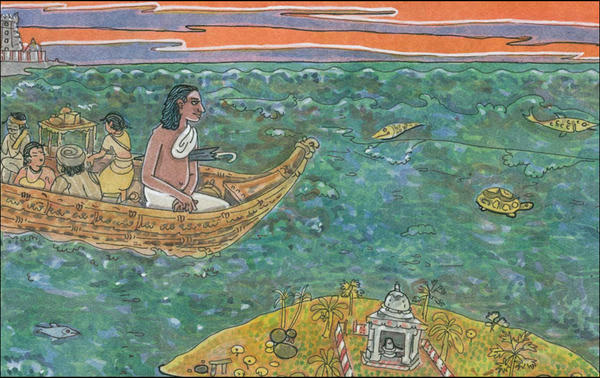

Muktiyananda made his way from South India to Ceylon as he was instructed, though that sounds easier than it actually was. On foot for hundreds of kilometers, he reached India’s southern shore sometime in the 1860s. Though a Tamil legend claims he magically flew across the 65-kilometer-wide Palk Strait, biographers tell us he came by more mundane means. In Eelathu Sitharkkal (translated as Siddhars of Eelam), author Muthaiyar narrates: §

In those days, Oorkavalthurai [Kayts] in northern Ceylon was an important port. Big ships used to come from India to Ceylon. Eluvaitivu is the first place that ships sailing to Sri Lanka from Nagapattinam in India will see. Muktiyananda reached Oorkavalthurai on a ship like this. From Oorkavalthurai he walked all the way to Jaffna. The first place he stayed was Mandaitivu. §

Muktiyananda arrived in northern Sri Lanka in the 1860s. Though he came anonymously to the island, this single soul would one day awaken the Tamils who slumbered under colonial rule, reigniting their faith in God Siva and their ancestral religion, Hinduism.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

Mandaitivu is an island off the Jaffna peninsula that measures 800 meters by 3.2 kilometers. It became a spiritually awakened place due to Swami’s presence. Even today, the island is known for its spiritual prowess and Siva temples. §

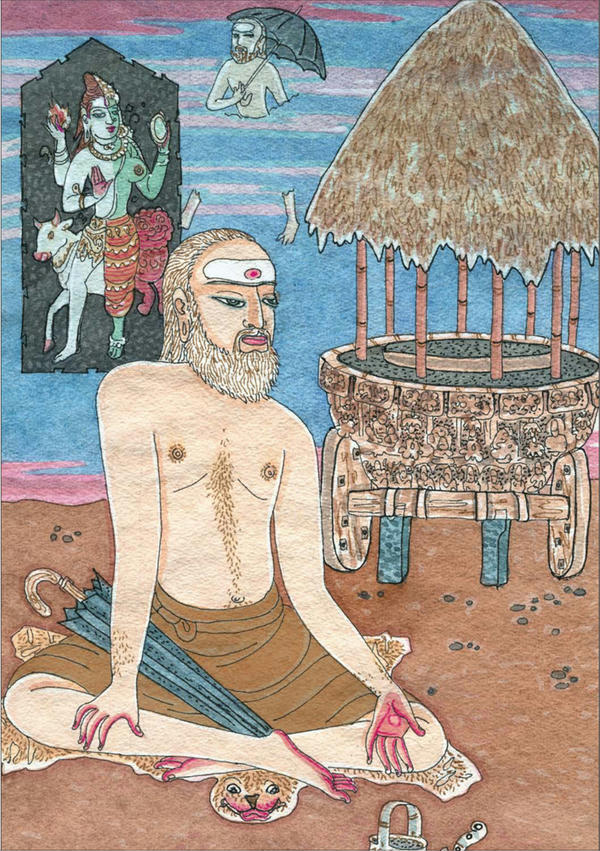

When Swami landed, he met a man named Nanniyar, who let the stranger stay in a hut near his home. It became Swami’s abode. The hermitage had a cow-dung floor and plaster walls, with a coconut-wood roof covered with thatched palm fronds. His bed was a small wooden platform, oddly just 1.25 meters long. Even today, there are remnants of his years there, including his bed; and residents of the area still fondly recall their great grandfathers’ stories of his presence. §

Before Muktiyananda sailed to Ceylon, a Chettiar named Vairamuthu had seen him at a temple in South India and invited him to come back with him to Sri Lanka. Muktiyananda replied, “You go; I will come.” One day Swami showed up at Vairamuthu’s home in Jaffna. When the wife said her husband was at the temple, Swami asked for some food and instructed her to set a banana leaf also for her husband. As soon as the wife was finished serving the visitor, her husband walked in and Swami offered, “Sit and eat.” §

Muktiyananda’s boat landed on a small island just off the northwest coast of Sri Lanka. There he moved into a simple hut. Soon he began walking daily to Jaffna on the narrow ithsmus to perform his marketplace mission.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

Ultimately, Vairamuthu gave Swami his house and all his wealth and became a sadhu himself, known as Chinnaswami. Swami made the home into an ashram called Kantharmadam Annathaanasataran near Nallur; and with the money created an endowment to feed devotees every day. §

Walking the six kilometers to Jaffna from Mandaitivu on the sandy isthmus became Kadaitswami’s daily habit, entering the market to give forth his spiritual wisdom. He would return to Mandaitivu in the evening, or stay in Jaffna, making camp on the steps of the Vannarpannai Sivan Temple or staying at the nearby public rest house. In subsequent years, he made use of centers built by his devotees in Ussan, Kantharmadam and Erlalai, where a bed and basic food was provided for pilgrims.§

Muktiyananda was a mysterious sadhu for whom there is no written record and no photograph, only a few crude artistic sketches. However, it is known that he had been a High Court judge in the state of Karnataka, and that he had mastered English, Sanskrit, Kannada and Tamil. His close devotees knew that he had taken the robes of a sannyasin due to a deep-seated change of heart.§

There is speculation, unsubstantiated, that Muktiyananda was given sannyasa diksha by Sri Narasimha Bharati, 32nd Shankaracharya of the Mysore Sringeri Math. In Siddhars of Eelam, N. Muthaiya observed: §

Between 1817 and 1879 Sri Narasimha Bharati was the 32nd leader of the Mysore Sringeri monastery’s Shankaracharya Pitham. He was a great siddhar who created many jnanis, yogis, siddhars and jivanmuktas. During his 62-year tenure, 40 years were spent outside [i.e., traveling]. His last 12 years were spent in spiritual service in Tamil Nadu. Together with his primary disciple and fellow siddhar Sri Sachidhanantha Siva, he traveled from village to village to create spiritual awakening among the people. At such an opportunity, the judge became Swami Muktiyananda.§

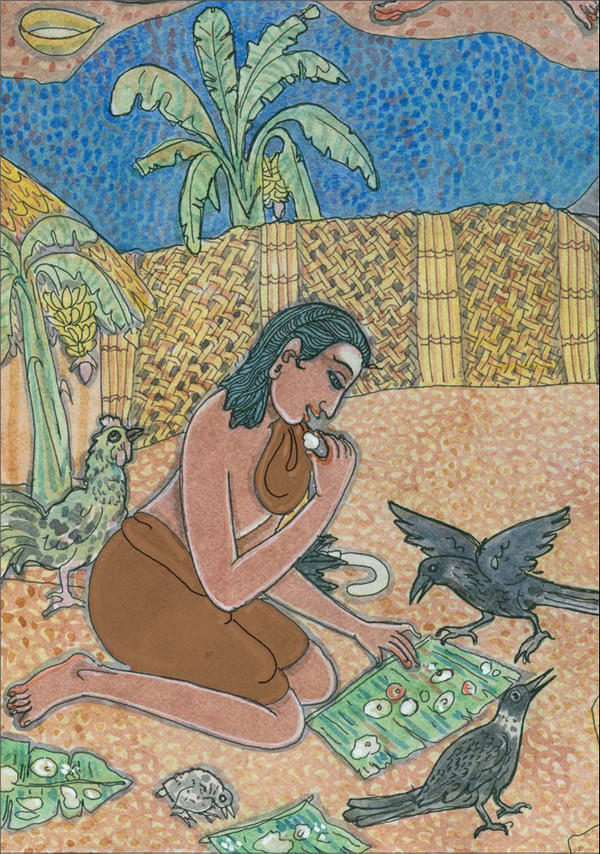

An early biographer, Brama Sri A. Subramaniya Iyer (1857-1912), wrote that Muktiyananda was born in 1810. Swami told the people of Jaffna precious little about himself. He told them that he had been sent to Jaffna by a rishi who had come down from the Himalayas, a man who ate among the crows. Muktiyananda ate with the crows. When he sat alone on the ground under a tree, crows would gather nearby, watching for scraps from the meal. It is said that he ate and drank almost anything that was given to him. §

Kadaitswami swept through the Jaffna markets, carried by lengthy strides and ever aware of his presence among the people. He was a mystery to one and all, an affable sage who somehow always brought joy to shoppers and prosperity to shopkeepers.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

Marketplace Monarch

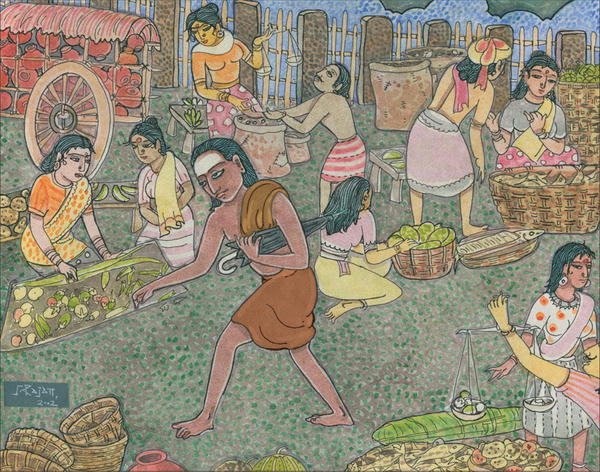

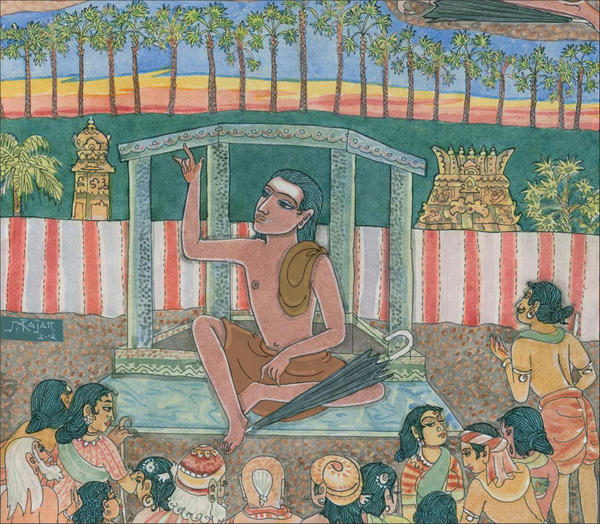

Muktiyananda spent his days at Jaffna Grand Bazaar, walking about or sitting under a huge, shade-giving banyan tree. The shops on the northern and western streets of this marketplace belonged mainly to the Chettiars, or trading community. Muktiyananda did not say his name, so people took to referring to him as Kadaitswami (kadai means “shop” in the Tamil language, so his name simply meant the swami who frequents the marketplace). It is common in Tamil culture to name holy men after places, for they often do not let people know any other name. History also knows him as Adikadainathan, “Lord of the Marketplace.” §

Kadaitswami would go to a shop and take a piece of bread. While they might object to such filching by an ordinary customer, shopkeepers were always pleased to relinquish a little of their stock to the swami, for they had come to learn that business was bountiful on days he visited. They would even pray that the tall sadhu might come and help himself to something. People observed, and these small signs gave them faith in the swami, faith in his powers to bless and magically influence the world around him. That is one reason Chellappaswami, his future disciple, was not as popular in Jaffna, for he refused to perform such miracles. Muthaiyar shares the following:§

Sometimes Swami would dance in the market and on occasion enter a stall and touch the coins. It soon became known that this brought prosperity to the proprietor, and every merchant waited eagerly for him to enter their premises and give his blessing. But not everyone received it. §

At times Swami would take a handful of coins and run down the road like a madman, with many kids running after him. Suddenly he might turn around and throw the money in the air, dancing in joy as the children rushed to pick up the coins. §

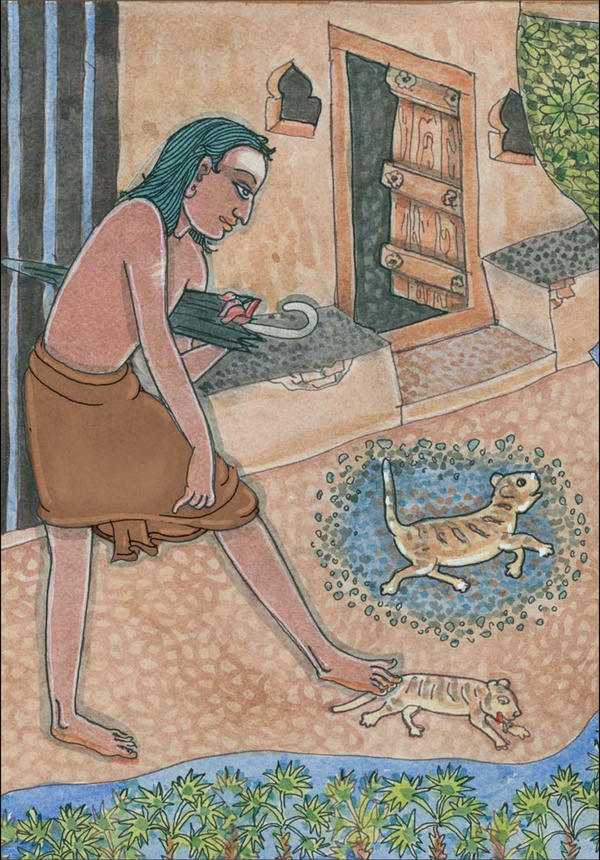

The real-life stories of Kadaitswami are full of miraculous happenings and healings. Chroniclers allege that he turned honey into arrack and arrack into honey. It was claimed that he never used a toilet, or had to. Decades later, his disciple’s disciple, Yogaswami, told his disciples that Kadaitswami performed more miracles than were attributed to Krishna. One day, Yogaswami narrated, Kadaitswami came upon a dead and decomposing cat, touched it with his foot and commanded it to get up. The cat came to life and walked away. §

Muthaiyar narrates another story:§

Thaandel of Valvettithurai, a devotee of Swami, went to see him at Vannarpannai. Hearing that Swami had gone to Mandaitivu, he set out walking there. It was high noon, and the sandy path soon became so hot that his legs and body were burning. Unable to tolerate it, he shouted, “I can’t stand the heat, Gurunatha!” At that moment, Swami, who was lying on his bed in Mandaitivu, got up and shouted, “Terrible, terrible, I can’t stand the heat!” He told one of his devotees to open an umbrella and shade his feet. The devotee did so without understanding why. After some time, Swami told him to put the umbrella away. Thaandel came in just then, prostrated at Swami’s feet, then stood, tearfully grateful for Swami’s grace.§

Muktiyananda was described as lean and tall, dressed in a dark veshti, carrying an umbrella under his arm. They say he was six feet four inches tall, had curly hair, piercing eyes and a long, pointed nose; his body was gangly, but well formed and of charming appearance. K. Ramachandran provided the following description on a radio talk he gave in the mid 20th century on Sri Lanka Broadcasting Corporation.§

Life and death held no mystery for Kadaitswami. Striding through the villages one day, he came upon a dead cat in the road. As witnesses watched, he nudged the carcass with his foot, as if to wake it up. Moments later the cat, revived, got up and walked away.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

No photograph of Kadaitswami was ever taken. The pictures of him that now exist are, in fact, drawings by an artist who was his devotee. These drawings depict him as having broad shoulders, long hands and a radiant smile constantly shining on his face. His long nose, lightly hooked at the tip, lent beauty to his face. There was a spring in his brisk, stately walk and humor in his talk that gave charm to his personality, say those who had seen him.§

He often smoked cigars. People would throw themselves down in an effort to have his cigar spittle land on their back as a blessing. K. Ramachandran noted in his radio talk:§

It is said that many are those who had swallowed his saliva and been cured of illnesses. Some gained siddhis. A person from Suddumalai became an expert astrologer. Another became a famous medical practitioner. In trying to explain the greatness of Kadai Swami, sage Yogaswami had said: “Even if Kadai Swami were to hold hands and dance with naked maidens, he would not lose his composure. Indeed, he is many times greater than even Buddha, Christ and the rest of them.”§

Perhaps because of the radical behavior of Kadaitswami and his devotees, the most orthodox Saivites did not closely mix with him, and he no doubt liked it that way. They were strict vegetarians who did Siva puja daily and followed a conservative path, while Kadaitswami placed no such rules or restrictions on himself. §

His heterodoxy reaches a zenith in the tale of his visit to a cremation ground where, to teach a radical lesson to a shishya, he bit into the charred flesh of a corpse. Such tales of outrageous behavior were the proud insignia of the Nathas. Many sadhus in and around Jaffna took Kadaitswami as their preceptor. In their world, such outlandishness was a sign of transcendence of social norms, a certificate of extraordinariness.§

In addition to Chellappaswami, Kadaitswami had a number of close brahmachari disciples, including Arulambalaswami, Kulandaivelswami and Sadaivarathaswami. Arulambalaswami met Kadaitswami as a young child of two and followed him from youth. Kadaitswami eventually sent Arulambalaswami to manage the Kantharmadam Annathaanasataran ashram. Kulandaivelswami was a district court secretary who gave up his career to follow Kadaitswami. The samadhi shrines for Arulambalaswami and Kulandaivelswami are at Keerimalai, where a hall was built in their honor near the Naguleshwaram Siva Temple. §

Honored as the guru of the land, Kadaitswami was unmoved by the adulation of the many or the animosity of the few. He lived simply, unto himself, accountable to none, aware of all. He would eat alone, among the crows, sharing his food with these creatures who, it is said, always call their clan to join.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

Sadaivarathaswami went to Kadaitswami with some other children when he was eight years old. The moment Kadaitswami saw him, he jumped for joy and took him aside, gave him a hug, took off the hat he was wearing and put it on the boy’s head, saying, “This is your initiation. One day you will be a fine swami.” The hat given by Kadaitswami was later put in a shrine and received daily puja. §

Two other men who gave up their worldly life were Sergeant Swami, also known as Chinnathambyswami, who renounced his career with the police force, and Vairamuthu Chettiar, Kadaitswami’s first Sri Lankan devotee, who met him in India, eventually renounced the world and became known as Chinnaswami. §

Miracle of the Iron Rod

Kadaitswami lived life striding through the countryside and various townships, stopping and staying in patterns discernible to no one. As his reputation grew, everyone wanted blessings from him. With the passing years, he had a sizable contingent of devotees, and anecdotes of his miracles were the devotional coin of the kingdom. We could imagine one such blessing, based on a true report, as follows. §

Kadaitswami burst into the entrance of a bustling market one day, with shoppers vigorously negotiating for the slightest amounts of everything from flour to fish. Down the road to his right were fresh fruits and vegetables in lavish variety, each kind stacked in neat geometrical pyramids at open stalls tended by the farmer’s family. Bullock carts were still lumbering in from the farther fields, laden with the morning’s yield. Every region had its market, a giant version of the modern farmer’s market, with the growers engaging directly with the buyers in a frenzied melee. In those days, everyone was a locavore. Villagers had no refrigerators, not even ice, so visiting the market was an almost daily chore for every household, and food was always fresh. The age-old drama played out, with the merchants trying to maximize their take and villagers trying to minimize their expenditure. §

A medley of prepared foods were on display in a separate sector. Pittu, a mixture of rice flour and shredded coconut steamed in cylindrical bamboo tubes, laid in steaming pots, fresh and ready to eat—the fast food of those days, but much healthier. Idiyappam (known as stringhoppers in English), that strangely wonderful spaghetti-pancake-looking treat made of a thick rice flour dough, were being steamed. Dosai and appam, made from a fermented batter of rice and dal, were being skillfully cooked on wood-heated iron griddles. Iddli, vadai, biryani, uthappam and uppama were all available. §

Each stall purveyed a plethora of curries, along with the obligatory triad of red, green and cream colored chutneys, stone ground from fresh coconut and herbs to complement the main dish. Here, at a glance, one could see and enjoy 8,000 years of culinary evolution which has resulted in the most varied and healthful vegetarian palette on the planet. Saivites were so uniformly vegetarian in those days that the word for vegetarianism in Tamil is saiva. No wonder they mastered the veggie diet, having no fleshy distractions.§

A man named Kandiah was part of a circle of devotees dedicated to Kadaitswami, but the two had never spoken. Suddenly, there the guru stood, an arm’s length away, his tall frame towering above the crowd. Looking down at Kandiah, Kadaitswami spoke in a deep, resonant voice, “I am coming to your home for lunch tomorrow, and I am bringing many guests!” It was not a request or a negotiation. §

Looking up at the improbably tall swami, Kandiah folded his hands together and paused for a moment in the hopes of saying something inviting, yet profound, grateful and reverent. All he could muster was a lame smile and a barely audible “Yes, Swami.” Swami turned around and left without a word. The rumor spread like wildfire. Kandiah had been chosen by Swami. Down the line of stalls, people greeted the news with joy, curiosity and downright envy. §

As he wandered home, Kandiah’s mind wandered to food. He had not eaten a full meal in five days. His family had simply sustained themselves on a little dal, the milk of the family cow and a compassionate neighbor’s occasional offerings. They owned the famous CSK Coconut Oil Mill, which was started by Kandiah’s grandfather, but the business had floundered. They lost their land and had to sell off the family jewelry, all except his wife’s tali (wedding pendant). Kandiah was too proud to ask anyone for help. How then would he serve the swami?§

Reaching home, he was struck by the oddly placed reminders of his old life: the tile floors, a luxury compared to the cow dung floors of neighboring huts, a finely carved chair with a silk cushion, a silver-plated chest with engraved artistry. He lost himself for a moment, remembering how, when times were better, they lived and had servants in a home five times this size. §

Kandiah announced to his wife, Ponnamma, “Kadaitswami is coming tomorrow for lunch!” Her immediate reaction was enthusiastic, for a spiritual master was about to step foot in her home. But as fast as the smile came to her face, it left when she pondered how to receive him. Turning to her husband, she queried as diplomatically as possible, “How would you like to receive the swami?” §

Her husband said nothing, but handed her a small pile of rupees. Looking at him with love and admiration, the good wife joyfully glanced at the handful of notes without counting it and confidently announced, “I will go to the market and be back with the food for tomorrow.” An experienced market-goer, she knew the money in her hand was woefully inadequate. §

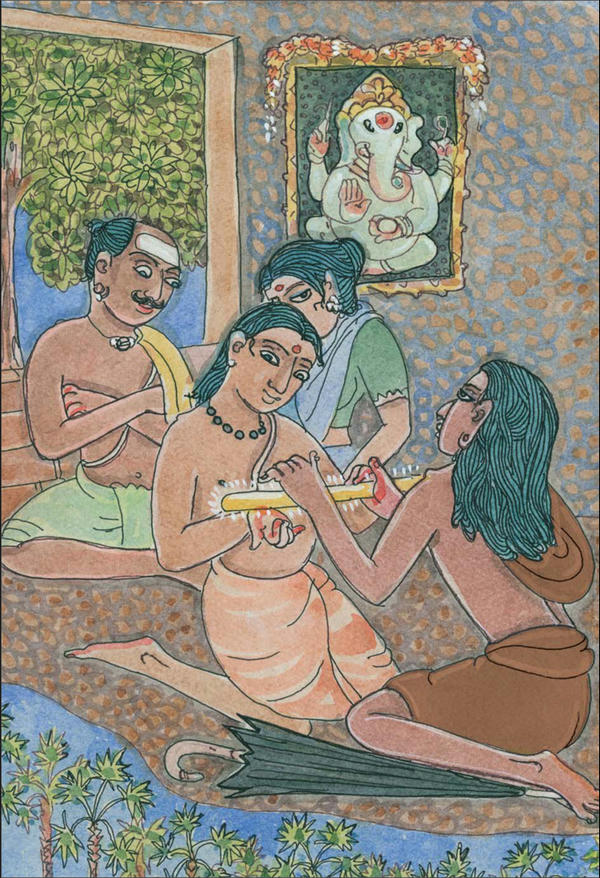

Ponnamma headed for the door, pausing a moment to clutch her tali, the gold pendant worn on a golden chain around the neck of all Hindu wives. Wives never remove this sacred symbol of marriage, and most faithfully worship it each morning. To lose it is considered unthinkably inauspicious. Nevertheless, setting out to the market, Ponnamma stopped surreptitiously at the goldsmith’s shop to pawn the tali for the need of the hour.§

The next day arrived almost immediately, or so it seemed since there was so much to do. The couple conscripted their two sons to help, and everyone was scrambling. By a quarter to noon, the last of the dishes was ready, kept fresh in the kitchen to be served hot only after the swami had seated himself on the woven palm mat that served as the dining room. Their scurrying was interrupted by a thundering thump on the door, “Kandiah, I have come!” And with him a grand following of guests, numbering, according to one biographer, in the hundreds!§

Ponnamma grabbed the camphor, Kandiah the lamp and the two boys held the tray as their parents placed the camphor on the lamp and lit it. Kandiah opened the door. Hands held in anjali mudra, he offered a reverent “Vanakkam, Swamiji.” But as they tried to offer the camphor flame in the traditional salute to holy men and women, Kadaitswami marched past and into the house. Obviously in good cheer, he gave Kandiah a hearty thwack on the back, “It’s a fine day, young fellow!” Swami sat on the mat prepared for him, indicating not so subtly that there had been enough niceties and he was ready to eat. §

Taking an unadorned clay basin in one hand and a jug in the other, Ponnamma poured water over Swami’s right hand as he turned it over and flexed his fingers in the cleaning gesture that begins all Tamil meals. Kandiah went to the kitchen where, one by one, his wife handed him the items to be served onto the banana leaf in an exacting order. Only men would serve a swami in those days, and the family would eat only after their guests had finished. §

When a once-wealthy family sacrificed to feed Kadaitswami in their home one day, he was moved by their hardship which did not diminish their hospitality. He called for an iron bar, turning it by his touch into gold. The family eventually sold the bar and prospered from that day onward.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

Ponnamma had purchased an abundant supply of every savory staple and treat for the large group. But Kadaitswami was a big and active man, with a matching appetite. As is customary in a Tamil home to this day, the host kept offering his guests more of each item as it disappeared, giving the sense that there was a never-ending supply. “It was a fine meal, Amma!” Kadaitswami finally announced, folding in half the banana leaf that had been his plate, thus indicating that he was finished. Relieved, Ponnamma relaxed. She literally had nothing more to serve. §

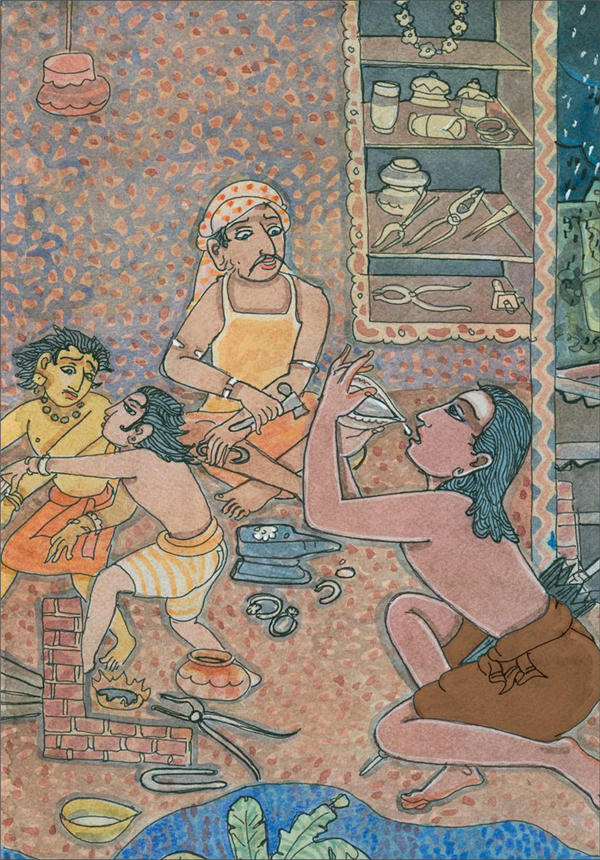

The next day, Swami visited again, alone this time, and asked Ponnamma to bring a piece of iron. Searching the family compound, she found a rusted piece of iron half-hidden in the soil and brought it to Swami. He took the rod in his hands and began to slowly chant, “Aum Namasivaya, Aum Namasivaya.…” then placed it back in her hands, instructing her to clean off the rust, wrap the rod in cloth and store it away. Abruptly, Swami then stood up and left. It was an odd departure, but Kadaitswami was nothing if not eccentric. A bit overwhelmed by it all, the family basked in the aftermath of Swami’s presence, so pure, so noble and mysterious. §

Four days later, when Ponnamma opened the cupboard, curiosity beguiled her to look at the rod. To her astonishment, it had turned to gold! Her husband had it tested by a goldsmith, and indeed, it was solid gold. Tears of joy in their eyes, Kandiah and Ponnamma later thanked Swami for his grace. Eventually they sold the gold rod, and their family business prospered once again. §

Saving a Fisherman

One stormy evening, Kadaitswami arrived shortly before dark at the house of a man who owned a fishing boat. The fisherman was not at home, and the swami acted strangely, so his wife was reluctant to let Kadaitswami through their compound gate. So adamantly did he insist that she relented. §

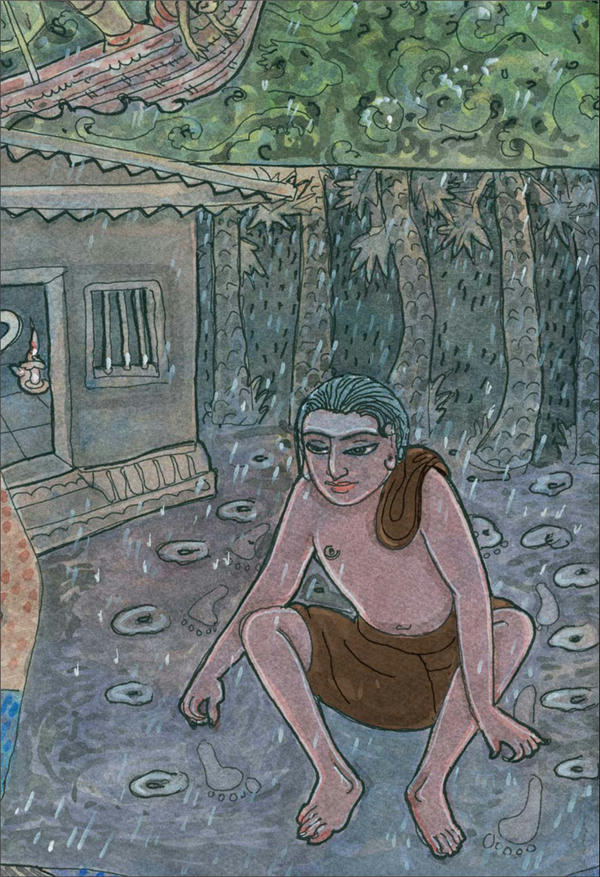

Entering the front yard, he went to a tree and sat down. About two hours later, the wife, who was still waiting up for her husband’s return, noticed that Kadaitswami was holding a stout pole and sitting on the ground digging in the dirt beside him as if he were trying to push himself along with this makeshift oar, all the while repeating “Ellello,” a word fishermen chant when working together to pull their nets. Yes, she thought, it looks as if he is pretending to row a boat, sitting in the mud in the dark. She went out in the torrential rain and pleaded with Kadaitswami to stop, afraid of the weird goings-on in her garden as much as what her husband would say when he came home to find the yard dug up. But Kadaitswami would not desist; in fact, amid the intensity of the storm and his work he seemed not even to hear her. §

When a massive storm capsized the fishing boat of a devotee one dark night, Kadaitswami sensed the danger from afar. He rushed to the man’s house and sat in the rain-soaked yard, thrashing about as if rowing, much to the consternation of the man’s wife who watched from inside in fear. Later, she learned, her husband’s life had been mysteriously saved at that same time.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

Three hours passed as the lanky sage performed this strange and strenuous drama. Unable to chase him away, she kept watch from the safety of her home. Finally, the swami stopped, rose to his feet and disappeared into the moonless night. §

The husband did not return until dawn, something that had never happened before. Many local fishermen’s wives had lost their husbands to the turbulent sea. The wife was waiting anxiously at the gate when her beloved approached, deeply relieved to see him but afraid of the scolding he might give her when he saw the yard. Mustering her courage, she shared the tale of the swami’s visit and the wild rowing episode. Hearing this, her husband prostrated at the spot where Kadaitswami had been sitting. Only then, dishevelled and exhausted, did he go to the open well to bathe. §

She brewed fresh coffee as he recounted that a severe storm had ravaged the sea just before dusk, capsizing his small boat. Struggling in the churning waters, he grew fatigued and felt death near, but wrestled with all his might to turn the boat aright. It was not working, and he grew weaker with every effort. Suddenly, one of the oars whacked him on the head, knocking him unconscious. When he came to, he found himself clinging to a plank, the boat right side up nearby in a becalmed sea. §

He told his astonished wife of a vision he had just when death seemed certain, a vision of Kadaitswami rowing the boat toward him, rescuing him from the sea. He had been saved, he said, by the grace of the guru. Both marveled at the miraculous interconnectedness of their experiences. They knew they had been touched by something rare and beyond their understanding. For the rest of their lives, they spoke of Kadaitswami’s supernatural efforts to save a drowning fisherman. §

Confounding Conduct

One day in the marketplace in Jaffna, Kadaitswami was begging at the stalls when he observed two elderly women stealing from the shops. They would take their concealed produce to the far quarter of the market, put it down on a piece of burlap, and quickly sell it below market price. No one was willing to apprehend the pair. They were surly nags, but they probably needed the money. Deciding their exploits should be stopped, Kadaitswami went after them one afternoon and provided each one a sound beating, one they would not soon forget. A policeman came by as he was knocking their heads together. Horrified to see an able-bodied man assaulting two feeble ladies, he arrested Kadaitswami and threw him into jail. §

In the middle of the night there was a loud commotion in the jail. Kadaitswami was pulling on the bars from inside and shouting at the top of his voice, “Don’t fear! I’m here to set you free.” He shouted that way for a long time until the jailer came to quiet him forcibly. Arriving at the cell, the jailer found the prisoner had vanished. He searched the yard, to no avail. The jailer awakened his superior to notify him of what was happening. When they reached the cell, the two found Kadaitswami asleep inside. The superintendent went back to bed, thinking his jailer was crazy or had had a bad dream. §

Within minutes the raucous scofflaw’s taunting began again, “Don’t worry! I will set you free!” Running again to the cell, they found it empty. A few minutes later, they saw the swami sleeping under a tree in the compound. Rushing to catch him, they were mystified by another disappearance. Again they heard him yelling from the cell. Shaking the bars, he called out, “Oh, I’m working on it. Soon you will be free!” Realizing they could do nothing to contain the man, they let him go. One of the guards was a sergeant named Chinnathamby. In later years, he renounced the world and became known as Sergeant Swami.§

One day Kadaitswami went into a shop to beg a few cents. The cashier ignored him for some time, then decided to have some fun with this old beggar, “I have a diamond ring here. If you can tell me what hand it is in, I’ll give you what you ask for.” The merchant put the ring in his hand and, placing his hands behind his back, switched it back and forth, then challenged Kadaitswami to guess. The swami declared that the ring was in neither hand. The merchant roared with laughter, thinking that he had really found a fool. Bringing both hands forward to reveal the ring, he was dismayed to find the swami was right. The ring was gone! Kadaitswami turned and walked out of the shop, followed by the distraught merchant. After some distance, Kadaitswami halted and spat the ring out of his mouth. The fellow was flabbergasted. Kadaitswami smiled and deadpanned, “Now you are caught.” §

At one time a group of boys followed Kadaitswami day and night, knowing that he sometimes drank arrack (the potent liquor made from palm tree juice, also known as toddy) and hoping to entertain themselves at his expense. But it was Kadaitswami who had fun with them. With the boisterous band not far behind, he visited several toddy shops, downing the potent drink. Continuing the game, Kadaitswami entered a shop where a metal worker had a pot of wax boiling on an open fire. He picked up the cauldron, drank some of the wax, then turned to offer it to the boys. But hot wax was not the intoxicating brew they had hoped would be his offering. Frightened by this bizarre spectacle, they fled down the lane, never to bother the swami again. §

Many thought Kadaitswami mad. He often danced in the streets and threw money into the air. One Dipavali day, in October, people were enjoying the festivities, buying new clothes for the year on this annual holy day. A merchant took his richest scarf from the shelf and gave it to Kadaitswami—who swiftly placed it on the shoulders of an approaching beggar and gave him a few coins. When asked later about this unusual gesture, he explained, “That man was the King of Nepal in a previous life.” Like the siddhas of yore, his vision was not limited to this time and this place. But seeing a deeper reality came with a price, the price of being misunderstood by ordinary folks.§

Several times, the police arrested him. As they took him away by the arms, Swami would lower his head and go along courteously. Two constables once took him before a judge, claiming he was mad and should be committed. It was customary for officers to wait outside while defendants stood before the judge. The magistrate asked Swami some questions, to which he responded in lucid English. The two got along well, in part, no doubt, because Swami had once been a judge himself. Both enjoyed the conversation. The judge summoned the police and scolded, “Release this gentleman immediately. There is nothing wrong with him. He is perfectly normal.” §

Like most Asian masters, Kadaitswami taught more indirectly than intellectually. When a band of truant boys took to following and needling him, he did not send them away. Instead, when they were watching one day, he grabbed a flask of molten wax in a jeweler’s shop and drank from it. This so frightened the boys, they never bothered him again.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

Combatting Christianity

In those days, the British Christian missionaries controlled most of the education in Jaffna. They had the best schools, based in the English language; and if Hindus wanted their children to attend these schools and get the most promising education, the children had to give up wearing their traditional clothing, their holy ash and pottu, submit to attending Christian religious classes and even attend daily mass. This insidious attempt to convert the children to Christianity was effective. Often unbeknownst to their parents, the children slowly adopted the Christian teachings. As intended by the Christians, this strategy disrupted the Hindu unity of the family.§

Kadaitswami, famed for his ever-present umbrella, was a judicial officer turned mendicant, an Indian who guided the spiritual life of Sri Lanka, a linguist who preached in the commoners’ marketplace and led a renaissance of Saivism among the Tamil people of Jaffna.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

Since they had to have a Western education to get a decent job with the British government, many were sent to the missionary schools, and among those many converted to Christianity, to their family’s dismay. These innocent children would attend morning prayers in school, then share in pujas in their homes, where their family life remained true to Saivite tradition. The compromise ruined their spiritual lives, which was exactly the missionaries’ purpose. Children found themselves on two different paths at once, one at home with mother and another in the classroom with the nuns. What Saivite rituals they performed were done without understanding, and what Christian services they took part in were performed hollowly as part of the daily school regimen. §

Kadaitswami served as a counterweight to this dogmatic onslaught. He was more articulate than any previous holy man in Sri Lanka, having been a lawyer and judge. He frequented Vannarpannai Siva Temple, about two kilometers from the marketplace, and there sang songs to Parvati. After worship, he gave rousing spiritual discourses. During his years in Jaffna, Kadaitswami spoke so often in front of the Siva temple that a thatched pavilion was built for him there. He stood on a platform in the pavilion and lectured to hundreds of men and women who came to worship or were on their way to nearby markets. An eloquent orator, he spoke with missionary verve. Though Swami’s native tongue was Telugu, he also spoke proficient Tamil (though in a dialect that was difficult for Sri Lankans to follow), along with Kannada, Malayalam and English. §

His upadeshas about the greatness of Saivism inspired renewed devotion in the people, who were accustomed to hearing sermons only from the Christian fathers seeking to convert them. Not for a long time had someone stood so boldly in public and said what was in their heart of hearts. Kadaitswami became the voice of their heritage, the protector of Saiva dharma, as he boldly reminded them of the beauties and potencies of their born faith. Over the years, tens of thousands heard him speak from the Vannarpannai platform, and large numbers of those were reinspired to hold fast to their ancient ways of Saivite Hindu life. §

There was, during those years, a learned scholar in Jaffna, twelve years Kadaitswami’s younger, by the name of Arumuga Navalar, the father of Sri Lankan Tamil prose. Before him, all Tamil was written in verse form. At one point in his life, Navalar translated the Bible, which he regarded as inferior to the Hindu scriptures, into Tamil to show his people the teachings it actually contains. §

These two firebrands were deeply dedicated to preserving Saivite culture in Sri Lanka, having clearly cognized the threats their people faced. They worked together to open several Hindu schools to offset the prevailing Christian education that so direly threatened the faith and futures of Tamil children. The first of these, known simply as Hindu High School, was begun at Vannarpannai in Jaffna, by the side of the Siva temple where Kadaitswami preached to crowds. This later became the Jaffna Hindu College, the foremost educational institution of the North. §

Magical Moments at Mandaitivu

One day at his place in Mandaitivu, Kadaitswami was preparing lunch with two disciples, Niranjananandaswami and Chinmayanandaswami. This was observed by Nanniyar’s wife. Suddenly, Kadaitswami shouted, “A karmi is coming! Quick, we must go.” Placing all the pots in a wooden box used for storing leftover foods, they ran away. Before long, a disgruntled man arrived and told the woman he was looking for Swami. She said he had just left. The man waited and waited all day, but Swami never returned. He waited for three days and Nanniyar’s wife fed him. As soon as the man left, Swami reappeared with his two brother monks and said, “Now we can eat.” They went to the storage box. The woman was thinking, “Ugh, they are going to eat spoiled, three-day-old food!” As they opened the box, steam was rising from each pot as if it had just been cooked, and—to the wife’s astonishment—the three enjoyed a fresh, hot lunch. §

Chellappaswami’s initiation came in the marketplace where his guru reigned. Kadaitswami had seen something in the eccentric young man that eluded others, the promise of a truly spiritual life and awakening, and he empowered his shishya by placing a large rupee coin in his hand, touching his back with the umbrella and sending him away.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§

On one visit to the island, Swami called Nanniyar’s family together and performed a homa in the backyard, as if doing an antyeshti (funeral ceremony). They assumed Swami was performing his own last rites, as a sign that he might soon leave his body. After the homa, he told them not to go to the temple for 31 days. “Now this,” they thought, “is strange, because Swami is still alive.” In a few days the family received news that their son had died in India during a pilgrimage to Chidambaram. Swami’s magical rites all came clear. §

Kadaitswami’s magic had a style, a kind of mystical DNA. How often he would know the events in people’s lives, events happening beyond the ken of the immediate players, events that affected friends and family, events separated by space, but often not by time. And he, the knower, the intermediary of the two seemingly unconnected events, would provoke some change that defied reason. §

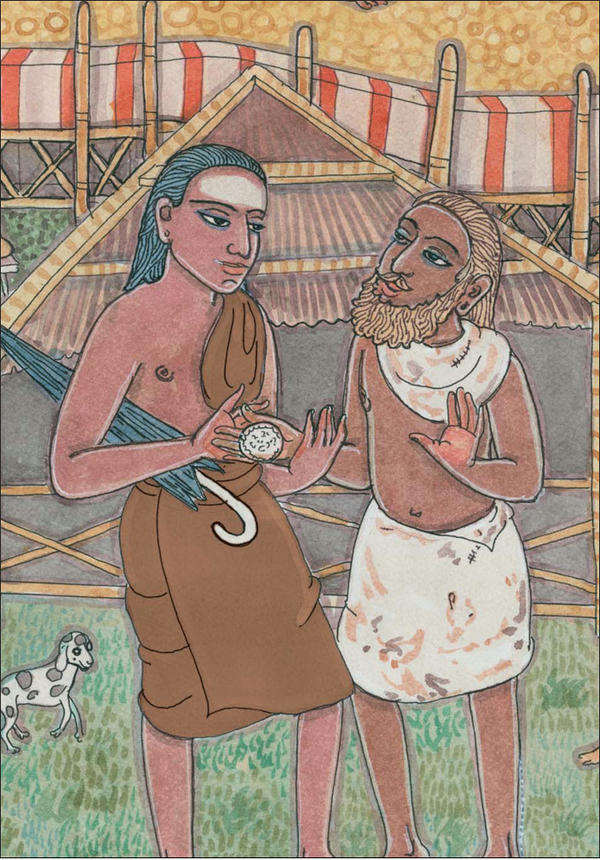

Chellappa Meets Kadaitswami

One day a young sadhu came to the pavilion. His eyes revealed a profound depth, and Kadaitswami recognized something special in him. After they spent an unknown time together, Kadaitswami met his disciple in the marketplace. Fetching a rupee from a woman peanut vendor, he wrapped it in a betel leaf and gave it to the young shishya. In those days rupees were large coins. The bundle covered half the palm of the sadhu who would later become known as Chellappaswami. Kadaitswami then struck him on the back with his umbrella and sent him away. §

Future devotees spoke of the coin-giving as Kadaitswami’s unconventional Natha way of initiating his shishya into sannyasa, the state of world renunciation. Decades later, Chellappaswami’s disciple, Yogaswami, recounted this great spiritual experience as it was told to him:§

Lo, with a silver rupee coin did Kadai Swami infuse his grace on Chellappar! The world looked upon him as a madman. From his empyrean height, he stood aloof, far from the madding crowds’ ignoble strife.§

The two met often during the next four years and went on long walks together. Chellappaswami said little or nothing of the time he spent with Kadaitswami, and history has almost no memory of it. S. Ampikaipaakan offers the following anecdote. §

To Kadaitswami, all devotees were the same regardless of differences in race or creed, high or low, rich or poor. He treated one and all with equal affection and remedied their physical and mental ills and their poverty, too. Knowing this, the devotees began to flock around him in larger numbers. There were many humble requests even from the poor to visit their homes. At such times they offered him their usual nonvegetarian meals, including liquor. Above likes and dislikes, he accepted what was offered.§

When this became known, there was anger and resentment amongst orthodox Hindu Saivites. Chellappaswami, the guru of Siva Yogaswami, could not bear to hear from devotees that Kadaitswami, whom he honored, takes liquor. It was something altogether unbelievable. Wishing to test him, he went to Grand Bazaar in search of Kadaitswami with a bottle of liquor carefully concealed under his shawl. §

As Chellappar went and sat beside him, Kadaitswami cried, “Oh ho, so you too have begun to treat me with liquor! All right, take the bottle that you have concealed under your shawl and open it. Let me share this with you and all these devotees here!” Chellappaswami, trembling, took out the bottle, but upon opening it found that the bottle was empty. The dismayed disciple asked forgiveness and returned back to Nallur teradi. §

On another occasion, Kadaitswami presented a bottle of arrack to Chellappaswami, saying it was time for his disciple to have his first drink. After all, did he consider himself better than his guru? Chellappaswami, unable to refuse anything his guru offered, took the bottle and tipped it up to his mouth. What had the smell of arrack to his nose tasted like honey on his tongue. §

What to imagine of the years they shared—a powerful siddha from South India and his inwardly inclined shishya from Jaffna exploring the depths of consciousness, the profundities of Saivism, that were so dear to them both? But imagine is all we can do. §

The Grand Departure

During the last few years of his life, Kadaitswami ceased going back to Mandaitivu and remained in the Jaffna area. He took a liking to a small, privately owned temple to Lord Nataraja in Neeraviady, a few kilometers from the marketplace. A hut was built for him in the compound behind the temple, where he stayed with Kulandaivelswami. This became his domain, a place of solitude and communion. He declared to his followers, “This is Chidambaram,” referring to the renowned temple of Lord Nataraja, the Cosmic Dancer, in South India, which is mystically thought of as the center of the universe. §

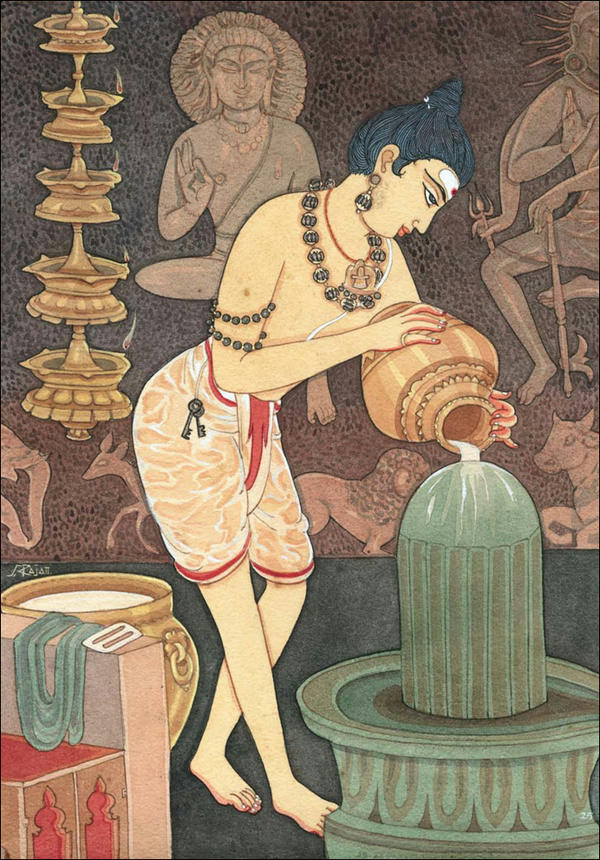

It was at this spot, on October 13, 1891, Shatabhishak nakshatra, that Kadaitswami made his Great Departure from this Earth plane. Kulandaivelswami was with him in those final moments. He had instructed his shishyas to inter his body in a crypt, as is often done with illumined souls. Kulandaivelswami oversaw the samadhi ceremony and entombment at the site of his hut. Soon afterwards, a large stone was placed on the spot, and pujas to it were regularly conducted by devotees. A year later, in 1892, in keeping with Swami’s orders, a sizable temple was built enshrining a Sivalingam from Benares, India, which took the place of the large stone. §

Nearly a century later, when the samadhi temple had fallen into disrepair, a group of boys who played cricket nearby began having dreams about a tall, slim man who told them they should restore the structure. When the parents heard about the dreams, they realized it was Kadaitswami the boys had seen and told them not to play there anymore. The boys rallied together, involved the Chettiar community and in the early 1980s began renovating the temple. §

In 1983, during Satguru Sivaya Subramuniyaswami’s (the disciple of the disciple of Kadaitswami’s foremost disciple, Chellappaswami) last visit to Jaffna, the Kadaitswami Temple temple committee, mostly youth, invited him to set the first stone for a new tower above the sanctum. He climbed a rickety, bamboo ladder to the top, set the stone and a small puja was performed. The renovations continued and the final consecration ceremony was held in 1985. §

When Kadaitswami departed from his body in the hut near the Nataraja temple, devotees interred the body in a crypt and built a Sivalingam temple at the sacred site. To this day, pujas are held in that temple.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •§