Chapter Eight

Yogaswami’s Early Life

Maviddapuram is a quiet village five kilometers north of Jaffna, best known for its ancient Kandaswamy temple, built in the 700s by Thissai Ukkira Cholan, king of the South Indian Chola empire, at the request of his daughter. Prior to that time the village, and the region between it, Keerimalai and Kankesanturai, was known as Kovit Kadavai, “God’s house.” It is mentioned by that name in both the Mahabharata and the Skanda Purana as a reputed tirtha, or holy spot. The sanctity of Kovit Kadavai is largely due to the hundreds of yogis and sages who did tapas there. §

According to the temple’s legend, the Chola king’s daughter, Maruthappira Valli, suffered from childhood an incurable disease which finally left her ears swollen, her jaw distended, her appearance so disfigured it was said she looked more like a horse than a human being. No remedy succeeded in restoring her health, and when she came of age she betook to endless pilgrimage, visiting temples throughout the Chola empire, seeking the grace of the Gods to remove her affliction. She was of saintly character, and her pitiable plight was all the more moving for it.§

Her misfortune came to the chance attention of the wandering sage Shanti Lingam Munivar, who advised her to go to the famed seaside temple of Keerimalai on the north coast of Lanka to bathe there daily in the medicinal waters of the temple tank. Maruthappira reached the place with her maids and attendants in the year 785 and devoutly fulfilled a strict regimen of penance and prayers, fasting by day and bathing long in the temple springs as advised by the sage. Her condition improved from the first until, in time, the affliction had gone and her natural beauty flowered as never before. §

Overjoyed with this new lease on life, Maruthappira lingered on in Kovit Kadavai, searching on every side for some means of repaying her debt and showing her gratitude to God. During her frequent walks to and from Keerimalai Sivan Koyil, she happened to witness the daily pujas of an old man, Sadaiyanar by name, who kept a small copper vel in the nook of a banyan tree, and worshiped it there with fervent love and affection. §

As a boy in Northern Ceylon, Sadasivan was surrounded by the religion of his community, a strict Saivism that despite foreign rule had survived intact. He would have seen many sadhus as he grew up, the holy mendicants and wanderers whose simple life was centered on God Siva, whose search was for Siva consciousness and grace.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • §

Gazing at this simple shrine one morning, Maruthappira felt a divine urge to build a proper Skanda temple on that spot. She sent an appeal to her father, explaining all and soliciting his help. The dutiful father, moved by his daughter’s transformation in far-off Lanka, responded at once, organizing a veritable army of temple architects, stone carvers and laborers, who arrived within weeks and set to work. §

It was a huge undertaking, yet fortune smiled at every turn. Ukkira Singan, the Kalinga king of Jaffna, after inspecting the project himself, immediately placed his wealth and resources behind it. It was he who later gained the hand of Maruthappira in marriage. The Deity for the temple, a handsome image of Lord Murugan known as Kankeyan, arrived from India along with a large staff of priests and others to manage the temple. They performed the consecration puja in great style and splendor, and thereafter the temple’s fame spread throughout the island, India and even to Malaysia. The village Kovit Kadavai was known from that time as Maviddapuram, the “horse-face village.”§

In 1619, during their third invasion of the Jaffna peninsula, Portuguese soldiers and priests destroyed the 900-year-old temple, leveling it to the last stone. Most of the larger blocks were hauled kilometers away for building a sea fort at Kayts, an island in the Palk Strait. Every major temple on the peninsula was similarly demolished during the colonizers’ stay; they left nothing standing. For 41 years they ruled the North with callous missionary zeal. It was their custom to build Catholic churches from and upon the ruins of Saivite temples they pulled down. §

The Dutch began their rule of Ceylon when Dutch marines evicted the Portuguese in 1658. Overnight, Catholic churches became Protestant churches under Dutch ministers and continued for 140 years, until the British displaced the Hollanders in 1798. The Dutch allowed some religious freedom. Indeed, a period of Saiva revival took place. Still, the rebuilding of the Maviddapuram temple did not begin in earnest until 1782, after a lapse of a century and a half. The Deities were all recovered, having been hidden in a well for most of the period. Encyclopedia Britannica gives us a glimpse into this era and the forces faced by Ceylon’s Saivites, colonial forces that subjugated the island until the end of British rule in 1948: §

The Netherlands was ardently Protestant—specifically Calvinist—and in the early years of Dutch rule an enthusiastic effort was made to curtail the missionary activities of the Roman Catholic clergy and to spread the Reformed Church in Sri Lanka. Roman Catholicism was declared illegal, and its priests were banned from the country; Catholic churches were given to the Reformed faith, with Calvinist pastors appointed to lead the congregations. Despite persecution, many Catholics remained loyal to their faith; some nominally embraced Protestantism, while others settled within the independent Kandyan Kingdom. In their evangelical activities the Protestant clergy were better organized than their Catholic counterparts; in particular they used schools to propagate their faith.§

During the period of Dutch rule in the coastal areas there was a revival of Buddhism in the Kandyan Kingdom and in the southern part of the island. While the Dutch felt great antipathy toward Catholicism, they indirectly contributed to the revival of Buddhism by facilitating transport for Buddhist monks between Sri Lanka, Thailand, and the Arakan (Rakhine) region in southwestern Myanmar (Burma). Such services helped the Dutch maintain good relations with the king of Kandy.§

Representing a new strand in the traditions of both Sinhalese and Tamil literature, Christian writings began to appear during the Dutch period. Although most of these new works were translations of basic canonical texts, some were polemics that targeted both Buddhism and Hinduism. The 18th-century writer Jacome Gonsalvez was among the most notable figures in Sri Lankan Christian literature. The Dutch East India Company’s [Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie] establishment in 1734 of the first printing press in Sri Lanka—used to meet the needs of missionaries as well as administrators—aided the proliferation of Christian texts.§

Today Maviddapuram Koyil is a thriving and popular temple, staffed by Adisaiva priests who manage its shrines and festivals with consummate care. The temple murtis include Shanmuganathan (Murugan), Sivalingam, the original copper vel and Vighneshvara (Ganesha). All of them receive daily pujas, and the temple continues to grow. It boasts a soaring rajagopuram, three spacious outer courtyards and five chariots. §

Sadasivan Enters this World

The temple was less imposing than now on the night in Vaikashi (May-June), Dhanishtha nakshatra, May 29, 1872, when a son was born to Ambalavanar and Chinnachi Amma in a simple house not far from its walls. The boy grew up in and around the most orthodox Saivite culture. His father, Ambalavanar of Columbuthurai, worked as a merchant on the eastern coast near Nuwara Eliya and was away most of the time. Chinnachi, a devout Saivite, raised the boy at their home in Columbuthurai, on the southwest coast of the Jaffna peninsula, until passing away when he was about ten. §

Stories of the Gods, the lives of the saints, temple customs and Tamil scripture he first learned from her. It is proverbial in Saivism that “the mother is the child’s first guru,” yet even had she known the spiritual destiny that awaited her son, Chinnachi could have done nothing better to prepare him than by passing on the ancient ways of Saivite culture as she did. She named him Sadasivan.§

It is traditional in Saivism that you do not ask a sannyasin about his past, so few questioned Yogaswami about his childhood or family, and none but a rare few received an answer other than, “I am always as I am now! The way I am now, I have always been!” He did once say he was born on a Wednesday, but that was as specific as it ever got. Over the years, though, he sometimes related certain stories to illustrate a point in talking to his devotees, and by comparing notes later they eventually pieced together a rough sketch of his youth. Inthumathy Amma shares the following: §

From his childhood days, when he took his mother’s hands and went to Nallur, the God of Nallur filled his heart. Circumambulating the temple and prostrating before the Deity became an experience that touched his heart. He enjoyed watching the hermits standing round the champaka tree. On seeing devotees bring different kinds of raw rice, bunches of bananas, coconuts and other articles of worship, he experienced complete withdrawal of his senses. He stood with tears streaming down his face when the brahmin priest offered lamps, camphor trays and other lamps to the luminous God Murugan.§

His mother departed from this world when he was very young. From what Swami told us and a few other devotees, it is possible to infer that she must have lived at least till his tenth year. Swami shared little about his childhood, but he did recount that one day after a meal he threw away the banana leaf, which still had uneaten rice on it. His mother, trying to teach him to not be wasteful, chided, “You will live by begging.” True to her words, he lived life like a beggar. He took delight in relating this incident to explain Saint Auvaiyar’s words, “Do not disobey the mother” (Thaai sollai thattaathey). §

Yogaswami once narrated the last time his mother took him to a festival at Maviddapuram Koyil, shortly before she passed away. He said there was a huge crowd circling the temple and he was holding tightly to her hand as they followed. He had on a veshti and a new silk shawl, which was wrapped around his waist at first, but somewhere it fell off and was lost. When a Tamil boy first wears a veshti, when he first has a silk shawl and when he walks still holding his mother’s hand are all indicators of his age. From these clues it is presumed Sadasivan’s mother passed away when he was around ten. §

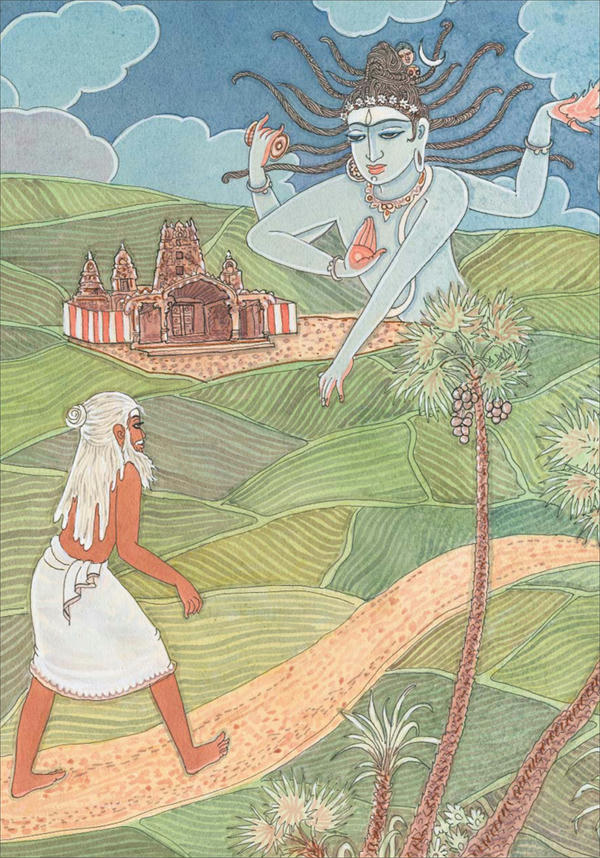

Nallur Temple, surrounded by agrarian fields, would be the nexus of Yogaswami’s life—the home of his guru, the place of his first immersion in the Clear White Light, the ground of his early tapas and the spiritual theater where he met with disciples. Here Lord Siva blesses Nallur, the “good place.”

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • §

School Days

For the next six years or so, following his mother’s death, Sadasivan was raised by his Aunt Muthupillai and Uncle Chinnaiya (Ambalavanar’s sister and brother). Aunt Muthupillai, a devout Saivite, was responsible for Sadasivan’s food, clothing and shelter, as well as his continued training in Saiva culture. He lived at her home in Columbuthurai, near the Jaffna Lagoon, six kilometers from Jaffna town. It was near the village kerniaddy, a large rectangular well where there was a small temple for Bhairava at which the family worshiped. Farmers working in the paddy fields in that area worship Bhairava, whose mount is a dog, for safety and protection. Chinnaiya, whose home was just 200 meters away, oversaw Sadasivan’s studies because Ambalavanar worked so far away and lack of transport facilities at that time prevented frequent journeys to Jaffna. §

Muthupillai spared herself no time or trouble in raising her new son. Chinnaiya was a Roman Catholic convert and his wife was born a Catholic, facts which had little influence on young Sadasivan. Muthupillai’s father-in-law, Nallar Ganapathy, a reputed Saivite astrologer in Columbuthurai, helped raise him as well. §

Sadasivan began his formal education in a Tamil school, but at age ten Uncle Chinnaiya enrolled him at St. Patrick’s College in Jaffna. Attending a Catholic school was not unusual in those days, since an English education could only be had from the mission schools. Civil service jobs were only available to English speakers, so these schools were always well patronized by the Hindus, despite the schools’ efforts to marginalize their faith. §

Like the Portuguese and Dutch before them, however, the British taxed the economy and resources of the island to the limit to help finance their worldwide empire. Secular education was more than they could budget in Ceylon, though they did offer token support to secular schools that taught English. Under foreign rule, times were uncertain for all Sri Lankans; a secure career and income required fluent English, whether for the civil service or private business. §

It was the custom for students registering to be given Christian names, such as Ford Duraiswamy or Mark Chelliah. Yoganathan was given the name John Pillai by the Franciscan monks who ran the school, but the name never took. During Sadasivan’s first year at St. Patrick’s, the village headman, Manniyakaran Muthukumaru, a stern old fellow who did not appreciate the Christianization of his culture, stopped the young student on the street as he came from school and asked him his name. “John,” came the reply. “No!” the headman shook his head. “Your name is Yoganathan.” It was a prophetic choice, meaning “Lord of Yoga.” S. Ampikaipaakan wrote in his biography, entitled Yogaswami:§

Muthupillai was an ardent Saiva devotee. She did not like that her brother Chinnaiya had joined in Catholic religion and that her nephew Yoganathan was studying in a Catholic college and had been given the name John. She used to give him Saiva books and Upanishads to study. Muthupillai is credited for saving Swamigal from the influence of Catholicism and for seeding Saiva devotion in Him.§

Yoganathan attended school through age sixteen. Language was a love of his, and he used his youthful years to attain a high degree of proficiency in both Tamil and English while reading avidly in subjects he liked. As precocious boys all over the world do, he sometimes assumed the role of teacher and instructed his classmates. Though he did well in his classes, he remained unenthused about school. §

Yoganathan was a quiet young man. While he did have school friends and was active, even restless, he often showed a serious, pensive mood. People felt his introspective, religious nature was due to losing his mother, and everyone presumed he would get over it in time. Throughout his school years, he was usually off somewhere alone with his thoughts or at the temple. He studied Tamil scriptures daily and learned a great many hymns of the Saivite saints, which he sang wherever he was. He memorized an amazing number of holy texts: Tirukural, Tirumurai, Auvaiyar’s poems, Tayumanavar’s verses, the Namasivaya Malai, and more.§

A devotee recorded the following incident. “One day in school one of the brothers was explaining the Biblical teaching that if someone strikes you on the right cheek, turn him also the other. Suddenly, Yoganathan walked up to the dais and gave a swift slap to the teacher. When the enraged teacher turned on him, the student left the class. This was the end of his formal education and the start of his spiritual quest.”§