Singing to Gaṇeśa§

Gaṇeśa Bhajanam§

गणेशभजनम्§

OMETIMES WE FEEL A GREAT LOVE OF GOD; SOMETIMES THE GRACE OF Gaṇeśa fills us with such enthusiasm and joy that our heart bursts in an overflowing expression of devotion. Our bhakti turns the word into song, which in turn is offered back to the Deity whence came this gift of divine love and bliss. There may also be other times when our heart is dry, our mind distracted; we feel forlorn and distant from Gaṇeśa. At such times devotional singing is a simple, sure way to raise our spirits up to a level where we can commune with Gaṇeśa once again. Or we may find ourself together with other Hindus who want to join in fellowship to joyfully affirm our religion and praise the Gods that guide us. So, we join together in song. In Hinduism this form of worship, called bhajana or kīrtana, is an age-old tradition, ranging from simple melodious repetition of the names of the Lord to the singing of inspired song/poems of great devotees. Remember that Hindu music has never been rigid like Western classical music, where a small deviation is viewed as error. In Hindu music melodies often vary from one village to another, singer to singer, one satsaṅga to another. Infinite diversity, tolerance and flexibility is a central theme of Hinduism and its sacred music as well. Deep devotion is the standard. Particular notes, in time, in tune or not are hardly noticed. If you are singing with genuine feelings and awareness, then even the song itself will be transcended. Before presenting some of these hymns for us all to use together, let us first consider the deeper meaning of bhajana as elucidated in a talk I gave at Kauai Aadheenam in Hawaii on October 16, 1978.§

OMETIMES WE FEEL A GREAT LOVE OF GOD; SOMETIMES THE GRACE OF Gaṇeśa fills us with such enthusiasm and joy that our heart bursts in an overflowing expression of devotion. Our bhakti turns the word into song, which in turn is offered back to the Deity whence came this gift of divine love and bliss. There may also be other times when our heart is dry, our mind distracted; we feel forlorn and distant from Gaṇeśa. At such times devotional singing is a simple, sure way to raise our spirits up to a level where we can commune with Gaṇeśa once again. Or we may find ourself together with other Hindus who want to join in fellowship to joyfully affirm our religion and praise the Gods that guide us. So, we join together in song. In Hinduism this form of worship, called bhajana or kīrtana, is an age-old tradition, ranging from simple melodious repetition of the names of the Lord to the singing of inspired song/poems of great devotees. Remember that Hindu music has never been rigid like Western classical music, where a small deviation is viewed as error. In Hindu music melodies often vary from one village to another, singer to singer, one satsaṅga to another. Infinite diversity, tolerance and flexibility is a central theme of Hinduism and its sacred music as well. Deep devotion is the standard. Particular notes, in time, in tune or not are hardly noticed. If you are singing with genuine feelings and awareness, then even the song itself will be transcended. Before presenting some of these hymns for us all to use together, let us first consider the deeper meaning of bhajana as elucidated in a talk I gave at Kauai Aadheenam in Hawaii on October 16, 1978.§

Singing to the Gods: Hindu Hymns of Invocation§

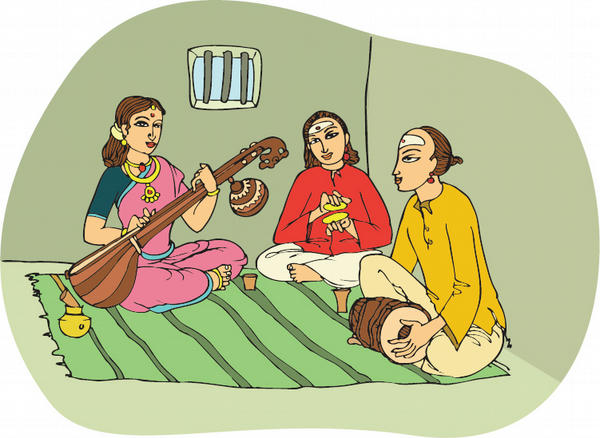

THE HINDU APPROACH TO GOD IS WELL-DEFINED AND MYStically oriented. it confidently proclaims that every soul is created by God and is destined to return to God; and it provides through its vast cultural and scriptural heritage both the intellectual insight and the pragmatic means for following that path and attaining life’s ultimate objective, spiritual realization. One of the legacies inherited by all Hindus is the rich and varied collection of sacred hymns, sung alone in the privacy of early morning worship or in gatherings of like-minded devotees whose combined invocations bring forth in each participant heightened communion with the Divine. There are many ways that Hindus offer devotion through chanting and song. Through the sādhana of japa yoga, the holy names of the Deities and sacred mantras are chanted both silently and aloud as a constant remembering. Pilgrims to the temple will assemble in the outer chambers to hear skilled musicians and singers well-versed in age-old devotional arts, fully capable of turning the mind toward God and away from the world through the subtlety and beauty of their lyrical offerings. Religious epics and stories filled with history and with parable are related to large congregations through dramatic choral presentation. Devotees gather in small and large groups throughout the world to chant in unison, generally led in turn by one among them and then another, singing their praises to the Gods to the accompaniment of the harmonium, drums, tambūrā and cymbals. This is called bhajana. It is certainly the most popular form of Hindu devotional singing.§

THE HINDU APPROACH TO GOD IS WELL-DEFINED AND MYStically oriented. it confidently proclaims that every soul is created by God and is destined to return to God; and it provides through its vast cultural and scriptural heritage both the intellectual insight and the pragmatic means for following that path and attaining life’s ultimate objective, spiritual realization. One of the legacies inherited by all Hindus is the rich and varied collection of sacred hymns, sung alone in the privacy of early morning worship or in gatherings of like-minded devotees whose combined invocations bring forth in each participant heightened communion with the Divine. There are many ways that Hindus offer devotion through chanting and song. Through the sādhana of japa yoga, the holy names of the Deities and sacred mantras are chanted both silently and aloud as a constant remembering. Pilgrims to the temple will assemble in the outer chambers to hear skilled musicians and singers well-versed in age-old devotional arts, fully capable of turning the mind toward God and away from the world through the subtlety and beauty of their lyrical offerings. Religious epics and stories filled with history and with parable are related to large congregations through dramatic choral presentation. Devotees gather in small and large groups throughout the world to chant in unison, generally led in turn by one among them and then another, singing their praises to the Gods to the accompaniment of the harmonium, drums, tambūrā and cymbals. This is called bhajana. It is certainly the most popular form of Hindu devotional singing.§

For thousands of years Hindus have gathered in conclave to share hours of the outpouring of their love of the Gods. Their chants have filled the temple chambers, the village hall and the private courtyard; but mostly it has filled and thrilled those who participated with a full heart. In the advanced stages of bhakti it matters little whether we are alone or with others when chanting the names of the Lord, for that mature state is steadfast in the higher devotional sensibilities, unruffled by the external world of name and form. Yet few have attained the serene heights of perfect devotion, and fewer still are steady enough to maintain such states once reached. The steadying support of others who also share spiritual goals in life can enhance the individual aspirant’s efforts, keeping him firmly on the Sanātana Dharma, the Eternal Path. When these sacred gatherings are regular, either daily or weekly, they generate a spiritual dynamic in the lives of all who participate, a shared energy to which all contribute and from which all can draw.§

The Working Together of Three Worlds§

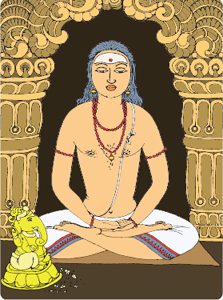

Bhajana is an essential part of the Hindu religious life. My satguru, Sage Yogaswami of Columbuthurai, Sri Lanka, placed great importance on chanting. He would say, “Sing, sing, sing. Morning, noon and evening we will chant with joyful hearts the blessed name of Śiva. Sing always of the Lord and meditate on Him who bestows virtue, wealth, happiness and liberation.”§

We join a revered band of devotees when we chant the praises of God. Hindus sing to God, to the Gods, to the multitudes of devas within their temples and home shrines who will gather around devotees when they congregate together almost anywhere. Each Hindu has his or her own guardian devas who are never far away, always available and willing to assist from an inner world of consciousness, from the Second World, or astral plane. These guardian devas attend Hindus from the time of birth or from a previous birth or from a ceremony or event occurring anytime in life when they enter the great assembly known as the Hindu religion. When two or more Hindus gather, each brings to that assembly—depending upon the personal sādhana that the Hindu has performed in this life and in past lives—his own devas to add to the throng.§

As sincere devotees meet, the inner-plane devas form a conclave in the same room, invisible to the physical sight but fully visible to the inner sight and sensed through the feeling of sanctity that pervades the atmosphere of the room. As the singing of the Hindu hymns commences, other Second World devas are drawn according to the sum of devotional intensity. These devas sing together in the inner planes in concert with the First World bhajana, and that calls others, until a multitude of beings in the Second World join in the same chorus as is being sung in the First World.§

Sincerity of Purpose§

We must realize that when we sing bhajana, the devas of the Second World and even the Gods of the Third World hear our intonations and are aware, too, of the depth of our devotion. They are fully aware of us, though we may be only partially aware of them. They know and appreciate the meaning of the words that we chant. For this reason it is very necessary that each one deeply understand the meaning of the words, even when those words are in Sanskrit. The meaning, the tones of the voice, the thought behind the meaning, the feeling behind the thought—all these give power to the bhajana, add their beauty to the sounds that radiate out from our love and devotion, taking that meaning, thought, feeling and sound from this macrocosm into the microcosm of the devonic world and through that into a greater macrocosm where the Gods live. High tones penetrate deepest, piercing through the microcosm into the great macrocosm that we know as the inner worlds. Also, concentration of mind, awareness of meaning and sincerity of inner feeling add to the ability of the chant to penetrate to spiritual depths or, in their absence, to remain little more than a sweet song hardly distinguishable from any other song.§

We must realize that when we sing bhajana, the devas of the Second World and even the Gods of the Third World hear our intonations and are aware, too, of the depth of our devotion. They are fully aware of us, though we may be only partially aware of them. They know and appreciate the meaning of the words that we chant. For this reason it is very necessary that each one deeply understand the meaning of the words, even when those words are in Sanskrit. The meaning, the tones of the voice, the thought behind the meaning, the feeling behind the thought—all these give power to the bhajana, add their beauty to the sounds that radiate out from our love and devotion, taking that meaning, thought, feeling and sound from this macrocosm into the microcosm of the devonic world and through that into a greater macrocosm where the Gods live. High tones penetrate deepest, piercing through the microcosm into the great macrocosm that we know as the inner worlds. Also, concentration of mind, awareness of meaning and sincerity of inner feeling add to the ability of the chant to penetrate to spiritual depths or, in their absence, to remain little more than a sweet song hardly distinguishable from any other song.§

Singing Is Prayer and Thanksgiving§

Most Hindu chants are a joyous praising of the Divine. They can also be a reminder that there are subtle inner worlds of existence, a pleading that we may be more aware of them and more in harmony with their great beauties and truths, and an invocation of the Gods and even of certain benefits which they are empowered to bestow. Our hymns are a thanksgiving for all that we have, for all the good that has been granted to us in life by our Gods, or during an immediate time span. Of course, we are only capable of such thanksgiving when we inwardly feel grateful, content within ourselves and not dissatisfied with our dharma, not struggling to oppose our karma in this life but to fulfill it by bringing it into harmony with our religion. True thanks must be offered, or true petitions made, with the mind and emotions and thought in a single accord as the Sanskrit lyrics are enunciated. How would the God perceive a devotee who is chanting something to him, pleading to him through the tones of his voice, but simultaneously thinking about something totally different and unrelated—or if he is not thinking at all but merely mouthing meaningless syllables? Obviously the devotee will be inwardly seen as insincere and shallow, saying things that he doesn’t really mean. It would be unwise to assume that the Gods are incapable of perceiving such states of mind. They are, in fact, more fully aware of the devotee’s inner feeling and thinking states during bhajana than the devotee himself.§

One bathes before coming to satsaṅga or bhajana. One prepares the mind and the emotion, knowing that he is, in a sense, on stage and performing before beings of great intelligence who are able from their microcosm to look into this macrocosm. These Gods are being invoked, and they will attend if the invocation is properly and sincerely performed with a devout heart and a mind that is one-pointed in spiritual pursuit. The devas in the Second World—which is the world of astral or mental bodies—will respond because their function, their fulfillment and dharma on their plane of consciousness is to help evolution in the First World, physical plane, and thereby further evolve themselves. They are spiritual helpers, working with the First World to open it up to the Third World. All the worlds work together when Hindu devotees gather together. The astral beings who work on the lower astral plane contact more evolved beings in the higher Second World who are able to themselves work with the individual and to invoke the Third World. The personal Deity is thus reached, and the blessings flood forth from within.§

It is very important that we are sincere when we chant these holy hymns that have reverberated in the nerve systems of uncounted seekers and sages down through the millennia. We would not want to be seen as insincere or inattentive, saying one thing and thinking another, or saying and thinking one thing and feeling another. Presenting ourselves to the Gods through prayerful song or just appearing before them in the temple precincts, we want to be in a most pious and profound state of mind. Ordinary affairs must be temporarily relinquished, along with ordinary feelings and thoughts. Yet, you would not want to pretend either. If you are unhappy when you come to the temple, they must see that unhappiness; and you must not try to cloud or conceal it from them or yourself. Then they can help. The Gods are going to see you the way you are from their vantage point in the microcosm looking out and into this macrocosm.§

Depth of Meaning and Feeling§

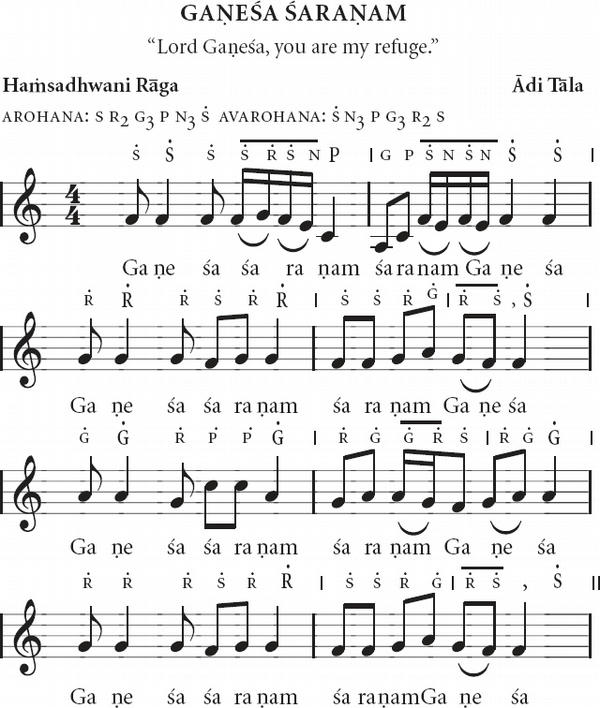

For those of you who may not know the Sanskrit language, it is necessary to make a special effort to understand, in English or in the language with which you are most familiar, what is being chanted in Sanskrit during bhajana. When we chant together “Gaṇeśa Śaraṇam,” it is essential that we know that it means “I take refuge in the darśana of Lord Gaṇeśa.” Even knowing the meaning is not enough. You must actually take refuge in the overpowering feeling of Gaṇeśa’s presence as you visualize His mūrti, or form. You must also be able to awaken to the higher emotional realms, to rise to a devotional mood as you are singing to the Gods, a mood that itself carries you into Gaṇeśa’s protective refuge, a mood that awakens you to the presence of Gaṇeśa’s love and compassion. If you are singing to the Gods with such genuine feelings, then the song itself has been transcended even while you are in the midst of your lyrical worship. Now, this is very important. That makes your chanting truly beneficial, beneficial not only for yourself and those who are with you but for all mankind.§

You could be singing Gaṇeśa śaraṇam, śaraṇam Gaṇeśa most beautifully, with no thought deeper than enjoying the sounds and realizing that you were on key and another in the room was not. Or you could be singing and at the same time thinking about some problem that came up during the day or an event that will take place in the days to come.§

Little benefit is to be derived from such an approach to bhajana. Similarly, when the time comes at a later date for you to be initiated into the art of meditation, there will be no real meditation if the mind is allowed to wander aimlessly, mulling over things of the past and imaginings of the future. Bhajana too, is a sādhana that requires preparation, attention and concentration. It is not an external performance meant to entertain the participants. It is an internal performance that invokes the inner-plane Gods and draws awareness deep within. Approach your chanting as a devotional sādhana. Let it be a time of communion with the deepest strata of consciousness within you and a communication with the Gods. Study the chants. Memorize their meanings so that as your voice goes out into the physical room your awareness simultaneously pierces into inner dimensions.§

From your own experience in the world you can understand how the Gods naturally perceive an aspirant whose body is joining in the bhajana but whose mind is elsewhere. People have come to you and said things that they did not mean. People have talked with you and you knew that they were thinking about something entirely different and thinking only absent-mindedly about the conversation. You have observed the results when people approach anything half-heartedly, perhaps preferring that they were somewhere else doing something else. Nothing permanent and valuable is ever accomplished even on the gross, physical plane by such an approach. Then how much more important is it that the subtle worlds, the deeper states of consciousness, be approached with mindfulness?§

The Group Helps the Individual§

A group that is chanting regularly, singing to the Gods day after day after day, gives the devas great power, a channel through which they can reach out and help other Hindus in the community and around the world. Within a hundred-mile radius inner-plane helpers assigned to guide Hindus, who are perhaps not religious Hindus, would come to the bhajana on the astral plane and be renewed themselves. Inner-plane helpers may also be renewed and inspired.§

A large satsaṅga or bhajana conducted regularly at the same time can summon these thousands and thousands of guardian devas together in a single conclave, renewing and inspiring them. Then they go back to the First World Hindu whom they are bound to guard and guide and in turn uplift and inspire him. He may be lifted out of the fog of the outer mind in its morass of confusions and become inspired to pay closer attention to his religion. He may awaken a desire to go to the temple, to serve others more selflessly, and on and on. Such things can happen just because a group of devotees get together and sing to God, feel what they are singing, know the meaning of the words they are saying and the implications within the meaning of the words. Of course, children love to sing; and bhajana is universally enjoyed by children of all ages, providing one of the most wonderful ways to bring your sons and daughters fully into the religion. They should attend group bhajanas often. The family itself can chant together in the shrine room each day for at least a few minutes.§

We want to take it all in, take in the tone, take in the thought, take in the feeling, take in the knowledge—take it all back to the source, back to the microcosm where you were living ten months before you were born in this physical world. You were there in the microcosm, fully aware, fully matured, working out your own spiritual destiny through helping those on this plane, awaiting another birth that would catapult you into an even greater evolution when you returned to the microcosm. So the microcosm is nothing with which you are not familiar. You came out of the microcosm and will return to it after the purpose of this birth has been fulfilled. It is really more your home than any structure on this Earth could ever be. So you are just contacting home when you invoke the Second World. It is nothing difficult. It is relatively easy, and you can do it night after night after night as you sing here to the Gods. Know that there are people listening, people just like you, people on the lower astral plane and people on the higher astral planes. They, too, join in the chanting where they are. If you had an inner ear, you could stop chanting and they would all be heard chanting simultaneously. This has been done; these inner-plane chants have been heard. The more regular the bhajana, the deeper it penetrates into the inner worlds. We believe that religion is the working together of the three worlds, and in our bhajana this working together is a joyous ritual simultaneously celebrated on all planes of consciousness.§

Association with Other Devotees§

One of the great benefits to be derived from bhajana is the association with other devotees, others of your religion who believe as you do and whose strength is added to your own. This is known as satsaṅga. Satsaṅga is the traditional meeting of Hindu Truth-seekers, gathered often to read from scripture or to receive upadeśa from a swāmī or their own satguru. The company of good men and women who themselves exemplify the Hindu ideals, who are striving, who are devout and virtuous, is to be sought after. Such association will immeasurably enhance your own efforts.§

It is very important in the world today that Hindu people gather together and express themselves in a religious way. Satsaṅga groups are formed all over the world wherever Hindus are found. The greatness of Hinduism lies in its diversity, and this diversity is also its greatest strength. This applies to the religion as a whole as well as to various groups within it. No single satsaṅga group will be quite like another, yet those within it must be in agreement on at least the major points of the philosophy that it represents.§

When you join a satsaṅga group, this becomes your religious experience and focus. It is different from the experience of worship in the temple, and it is different from private meditation and devotions in your home shrine. When you go to worship in the temple, you are there alone even though others may be present. It is a most sacred and individual experience, a time set aside for communion with your personal Deity. Within the satsaṅga group, however, within that kind of saṅga, you are sharing your devotion with others. You temporarily set aside your own mind, your karma, for a period of time and work your mind within the context of the group, which is the combined mind or karma of those present. This by no means should be taken to be a total involvement or entangling of the various karmas, but is a temporary combining or merging of karmas for those few hours each week when the satsaṅga meets together.§

I have often said that the individual helps the group and the group helps the individual. This is to be clearly seen in the working of group devotions and chanting in satsaṅga groups. We are inspired, lifted above our personal concerns and able to give our thoughts entirely to the high purposes of the satsaṅga; and with everyone present doing this, a dynamic vibration is created, an environment that is conducive to further progress on the spiritual path.§

Sharing Individual Karmas§

There are many religious groups throughout the world sharing the same philosophy and beliefs, chanting the same bhajanas and meeting together regularly. Some of these groups are productive, while others are unproductive. The actual results which manifest as a consequence of the gathering of a satsaṅga group are totally dependent upon the combined karma of the group as a whole.§

The one mind of the group is made up of both the positive and negative karmas of each member. This does not mean that if a group is unproductive or unhappy that certain members should be singled out and sent away, for that would only serve to create yet a greater unseemly karma for the outcast as well as for the group that inadvisedly cast him out. Rather, this indicates that the group must perform a deeper sādhana, a greater disciplined effort, that it must make a special effort to feel inwardly the meaning of the words as they are chanted and be in tune with the extraterrestrial vibratory rate of the devonic world. The group may also ponder whether the social period is excessively long, whether too much emphasis is being placed on the foods being served and whether one or more members are bringing their personal karmic implications and involvements into the group rather than taking these matters to the feet of the Lord. Above all, the group should realize that a problem exists within the mind of the group, which is no particular individual’s fault or problem. It is simply an effect of accumulated and combined karmas of the entire membership and must be faced in this impersonal way.§

A productive group is also a harmonious group, a useful group. Its members will want to distribute religious literature as a natural overflow of the energies that well up from within them during the satsaṅga. They will want to give food to the hungry. They will not be able to neglect the needy. They will naturally want to host a Hindu family newly arrived in their community, to visit Hindus in the hospital, to write letters for them, talk to them and see that they are properly cared for. There are so many practical things that a satsaṅga group can and should involve itself with, but this is possible only when all members are of a one mind, a one harmony.§

If the group is an unproductive group, it will be found to be a group that is inharmonious and argumentative, one in which the asuric forces are perhaps more prevalent than the devonic forces. This must be dealt with positively, not run away from or avoided. If asuric forces have penetrated the group, it is best to chant sitting in a circle, thereby creating enough magnetism to lift the consciousness of the entire satsaṅga simultaneously. If the group is a harmonious group, then all may sit, as at traditional Hindu gatherings, with the women on one side of the room and the men on the other. It is always preferable to sit on the floor, for that releases certain forces from within the body that can greatly enhance the spiritual life of man. When we worship in a temple, we receive individual attention from the great beings of the Second and Third Worlds. That is our time for personal communication with the inner worlds, with the inner realms of our own being. But satsaṅga is different, and that difference should be realized by all present. It is a group religious experience. It enhances both the personal karma of every member as well as the collective karma of the one mind which is the saṅga itself.§

I urge each satsaṅga group to look sincerely into its productivity and to seek creative ways that it can be useful to its members and to the community in which it lives. It is important that we use our energies well, that we do not waste energy, do not waste our lives. Satsaṅga groups can search out ways to help the many thousands of Hindus who have migrated from the Holy Land to all parts of the world and would benefit from a kind word and a compassionate smile.§

Conducting Satsaṅga§

There are many ways that satsaṅga groups can be conducted, and there will be established groups with their own routines. New groups just being formed may wish to follow our schedule of twenty minutes of bhajana followed by twenty minutes of scriptural reading or upadeśa and then another twenty minutes of bhajana, making a total of one hour. It is customary to have satsaṅga groups move from one home to another each week or each month, and, of course, the leader and host of the satsaṅga that week is always the person in whose home the group is meeting. He or she would select the reading or recording to be used that week, or arrange for a talk by a swāmī or other spiritual leader. The host would also arrange the room, preparing a small altar which could have a picture of the Deity—Lord Gaṇeśa is agreeable to all—and pictures of the gurus of the various members of the satsaṅga, for all will not necessarily share the same preceptor. As a satsaṅga group grows in strength and maturity, these and other ways of helping our fellow man will blossom forth. That is the first sign that the satsaṅga has done its work on the inside, has begun to fulfill its purpose.§

A Special Collection Of Hymns to Lord Gaṇeśa§

For Young and Old Alike§

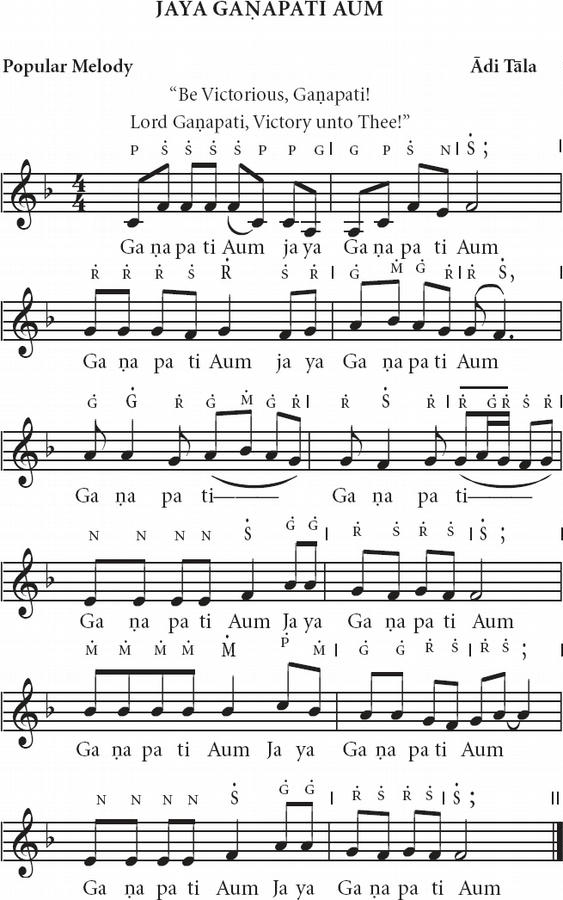

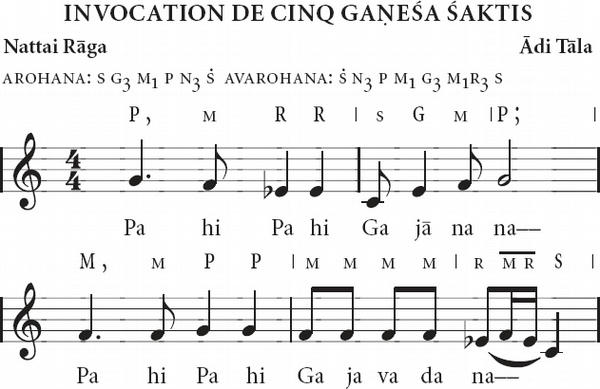

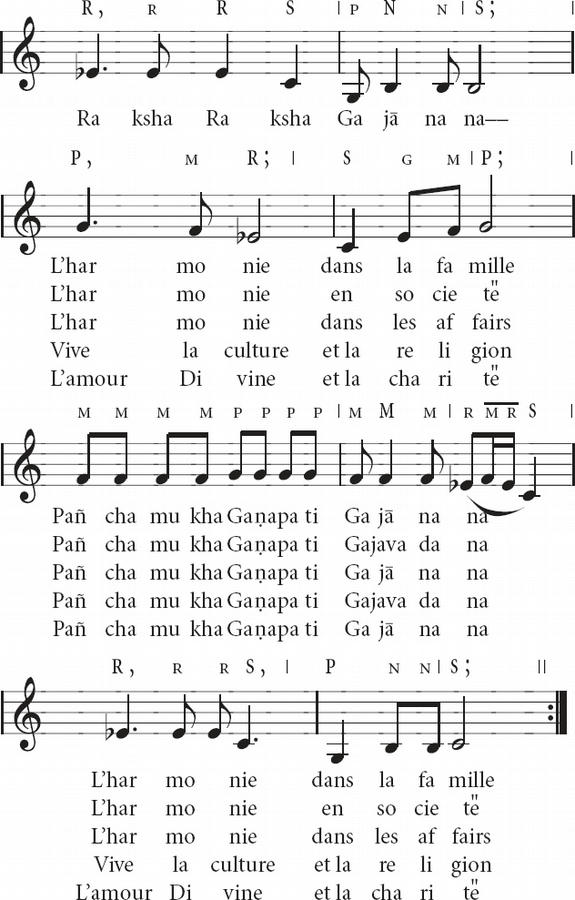

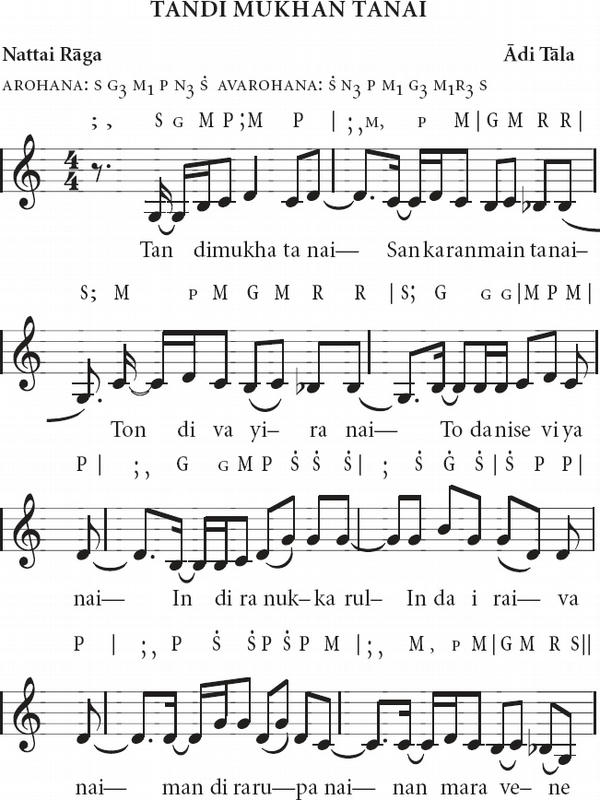

On the following pages we have assembled several hymns for individual or group singing and chanting. We have put the chants into Western musical notation so they can be played easily on a harmonium. A free translation of the Sanskrit into English has also been added to inspire high-minded thought and visualization based on the meaning of the songs. Usually one person leads the group, and then another, with the leader chanting the verse initially, then the entire group repeating that verse once. The leader then chants the second verse, and so on. Often the leader, if he or she is musically adept, will make embellishments on the musical line; but the group generally repeats the verse in its simple form. Many chants start off slowly and gradually pick up in speed and volume. The length of the bhajan is left to the leader’s discretion, but is usually limited to five or ten minutes.§

These songs may be sung during formal bhajana and informally to yourself at other times during the day. Sing them during your morning sadhana period and silently to yourself throughout the day. Sing them before meals and to the children just before they go to sleep. Sing them as you work and in the car as you travel. When you are discouraged, sing. When you are inspired and creative, sing. When you are upset, sing. When you find yourself waiting somewhere and feeling there is nothing to do, sing to the Gods. Sing with a full heart. As you sing, listen for the silence within the sounds; for that silence is itself the voice of God.§

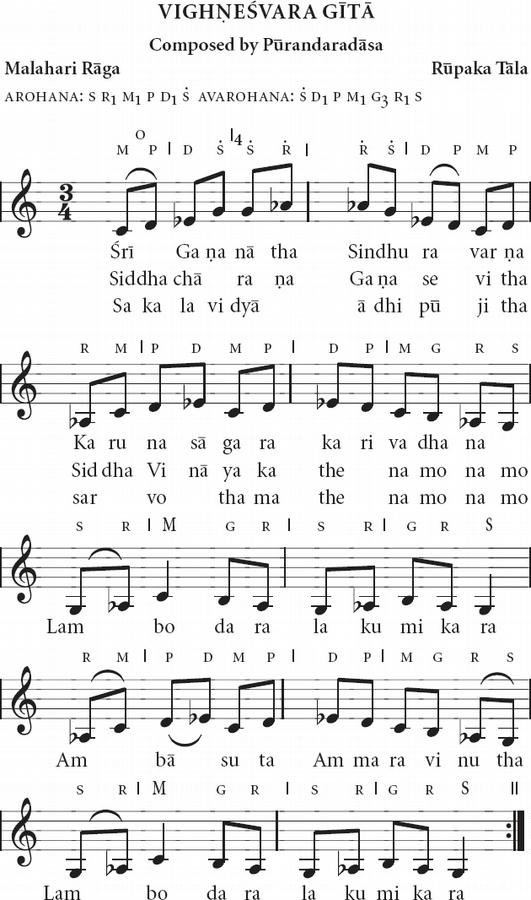

Gītā§

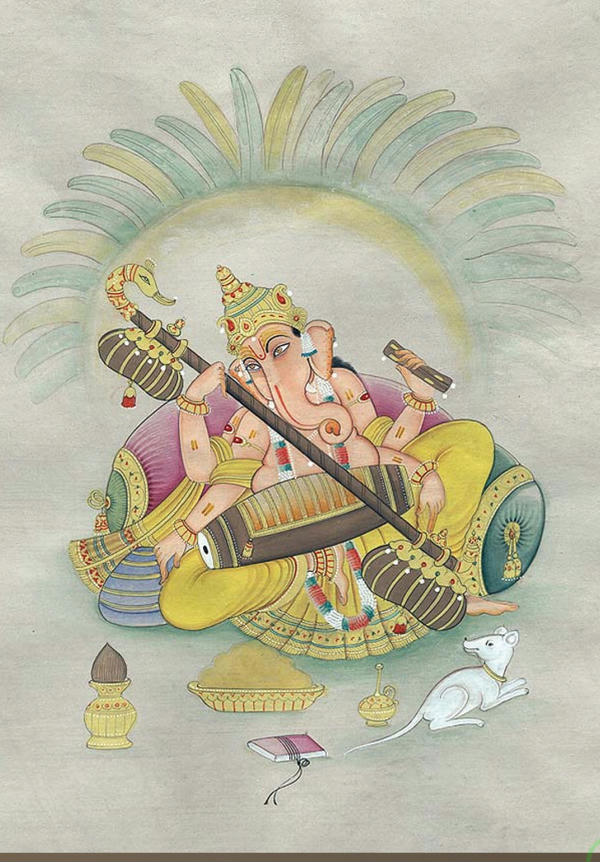

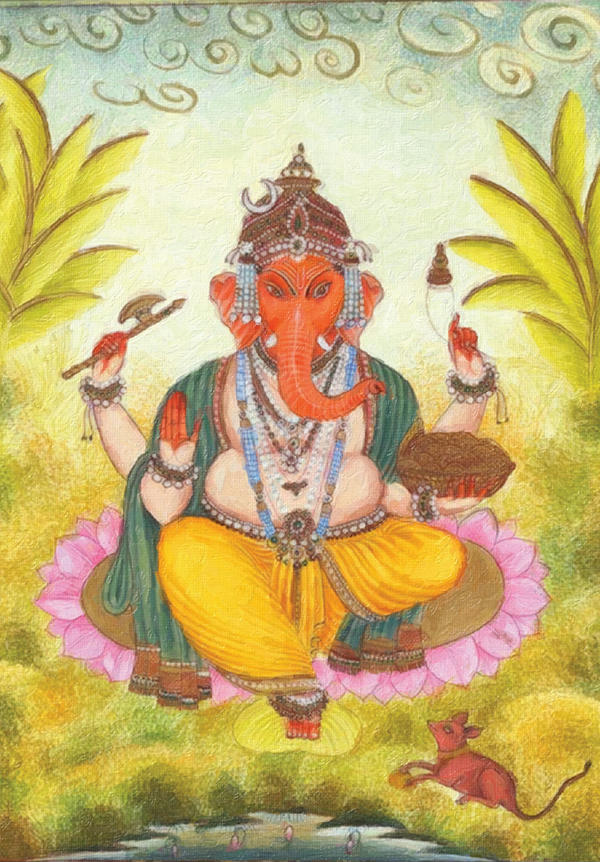

Gītā means song. Gītās can be sung solo or in unison by a group. The pace is relaxed. The words aid in devotional visualization. We seek to invoke the darśana and śakti of Lord Gaṇeśa, picturing Him in our minds while concentrating on His divine attributes. A deep communion with the joyous Lord is attained. Vighneśvara Gītā is often the first song taught to beginning students of Hindu music. Sing with all your heart this ode to our Loving Gaṇeśa. He will hear. Yes, He will hear. It is important to realize that, with His big ears and His astute mind, He knows everything at every point in time, even when eating a modaka. This is amusing. So, sing out loud; sing boldly His songs; and His grace will pour upon you with all the abundance under His control (which is actually all abundance).§

SONG TO THE LORD OF OBSTACLES§

verse 1 O Gaṇeśa, You are the red-colored leader

of the gaṇas, the ocean of compassion,

O elephant-faced Lord.§

verse 2 The siddhas and chāraṇas ever in Your service, the grantor of all

tattainment. O Vināyaka, we bow to You again and again.§

verse 3 Master of all arts and knowledge, the best

one of all, we bow to You again and again.§

refrain Big-bellied Lord who blesses all with prosperity, Pārvatī’s son, you are praised by all the Gods.§

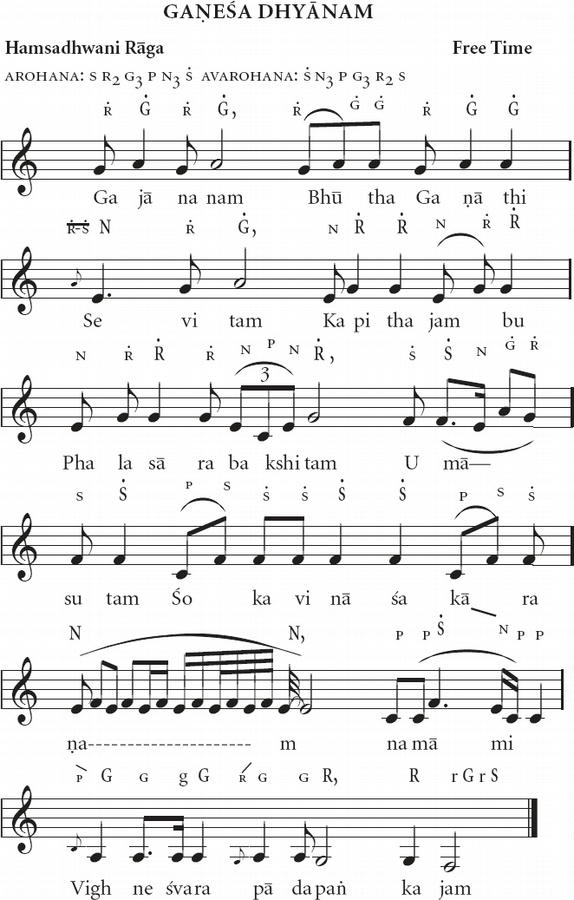

Dhyānam§

Dhyānam means “meditation.” This form of song is usually done solo, slowly, in free time, with no instruments other than a drone. More prayer than music, the words of a dhyānam are often from our ancient Sanskrit scriptures. For singers, it is a devotional offering. For listeners, the words direct the mind to commune silently with Loving Gaṇeśa. A short meditative silence following any dhyānam is traditional. Not enough can be said about meditation. It is the perfection of the peaceful mind. What makes the mind not peaceful? Well, Gaṇeśa would explain in His exemplary way, “Among the realms beyond My reach, one is fear.” Still, He can help, for fear is within His control, even though it resides as the emotion within the chakra directly below the mūlādhāra chakra upon which He sits: the four-petalled lotus of great beauty and strength rising above the waters of memory. Further below Him is the chakra of anger and rage in which the mind gives up its control to asuric forces. He, our loving Lord, prays for those in the state of anger, because mind and emotions out of control seals us from His grace. So, sing the song to lift up the purusha into its own pristine glory, and begin to change. That is the message of our loving God.§

GAṆEŚA DHYĀNAM, “MEDITATION ON OUR LOVING GAṆEŚA”§

Translation: O elephant-faced Lord Who is served by all creatures and satisfied with the juice of kapittha and jambu fruits, son of Umā, remover of sufferings and pains, O Remover of Obstacles, Vigneśvara, I bow at Your lotus feet.§

Bhajana§

Bhajana means adoration or worship, often by responsive group singing. A leader sings a phrase; the group repeats it exactly. Bhajanas usually have a strong rhythm, sometimes slow and steady and then fast, sparking attention, and raising the group energy. Bhajana is dynamic japa. The goal is concentrated communion with the God. Three bhajanas follow, two from tradition and one from recent times.§

Bhajana means adoration or worship, often by responsive group singing. A leader sings a phrase; the group repeats it exactly. Bhajanas usually have a strong rhythm, sometimes slow and steady and then fast, sparking attention, and raising the group energy. Bhajana is dynamic japa. The goal is concentrated communion with the God. Three bhajanas follow, two from tradition and one from recent times.§

PAÑCHAMUKHA GAṆAPATI§

This song was inspired by the eight-foot-tall granite statue of Pañchamukha Gaṇapati that we installed on the north shore of Mauritius, the Pearl of the Indian Ocean. This majestic five-faced, ten-armed Gaṇapati looks east toward India over azure blue seas—a towering reminder of the original home of the nation’s Hindus and of the importance of harmony in life. The greatest linguist of all time is He who holds time in ten hands, balancing it moment to moment by slightly moving His magnificent trunk. Yes, language is no mystery to our loving Lord. He knows them all. The island’s official language, French, and its sweet child Creole are perfect mediums for bhajana. All Creole vernaculars of the world are dear to His ears. They are languages of the heart.§

verses: O Five-faced Lord of Gaṇas, let there be harmony in the family, in society and in all our business affairs. Long live culture and our religion. Grant us love of God and charity for all.§

refrain: O Elephant-Lord, protect and heal us.§

Natchintanai§

The venerable sage, Asan Yogaswami of Jaffna, Sri Lanka, sang many songs of God, Gods and his beloved guru which contain profound religious and metaphysical teachings. These songs are called Natchintanai, meaning “good thoughts.” In one famous ode to the One God, Śiva, Yogaswami invokes Ganeśa in the first verse, before proceeding to sing of the One. Using traditional images, he alludes to a famous story where Lord Ganeśa gave His grace to Lord Indra, king of the Vedic devas. He also speaks of the ancient mystery teaching that Lord Ganeśa’s form is the mantra Aum itself. Thus did Yogaswami affirm the teaching to worship our loving Lord Ganeśa first before beginning any worship or task.§

The venerable sage, Asan Yogaswami of Jaffna, Sri Lanka, sang many songs of God, Gods and his beloved guru which contain profound religious and metaphysical teachings. These songs are called Natchintanai, meaning “good thoughts.” In one famous ode to the One God, Śiva, Yogaswami invokes Ganeśa in the first verse, before proceeding to sing of the One. Using traditional images, he alludes to a famous story where Lord Ganeśa gave His grace to Lord Indra, king of the Vedic devas. He also speaks of the ancient mystery teaching that Lord Ganeśa’s form is the mantra Aum itself. Thus did Yogaswami affirm the teaching to worship our loving Lord Ganeśa first before beginning any worship or task.§

Invocation of the Elephant-Faced Lord§

O elephant-faced Lord, son of Śaṅkara

with voluminous belly and earrings, who granted grace to Indra,

the king of the devas. You who are of mantra form I will never forget.§

Throughout time, Lord Gaṇeśa as Aum has come into the lives of elemental beings, men, women, children and even the Gods themselves. For His is the office of gatekeeper. Nothing can begin without His nod of approval; and nothing can end without giving thanks and showing appreciation to Him, for every end is a new beginning.§

Loving Gaṇeśa has a mystical symbol, the swastika. It represents the power of the matured mind: a mind that has flexibility; a mind that has resilience; a mind that has compassion; a mind that has the twice-born strength to finish what has been begun; a mind that is in touch with the divine—above, below and to either side. The swastika represents Gaṇeśa, to be sure.§