New Art from Our Indian Artist Baani Sekhon

As most of you know, we are working to have new portraits of eight of our Satgurus, so they are all represented in a euphonious way. Four days ago, we received the latest one from Baani Sekhon. It is of Rishi, who has no known name. Since he began his life in the Himalayas, we simply call him Rishi from the Himalayas.

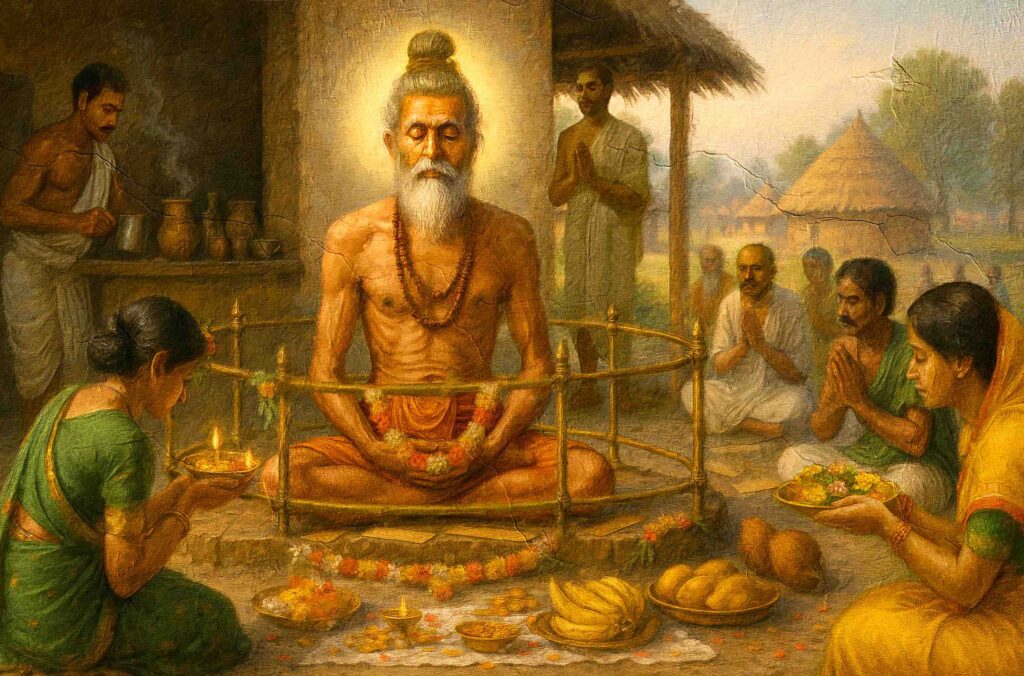

We share Baani’s interpretation today. It depicts a part of his life—seven years of it—spent sitting in a tea shop in Bengaluru. Devotees eventually placed a brass railing around him to keep people from touching the silent and motionless saint. Baani shows how he became revered in the village. She subtly intimates how, at times, something magical happened around him: pieces of paper would fall from above, and on them would be written answers to the thoughts of those present. These became cherished remembrances of their time with him.

We include, for the brave, a long excerpt (not his whole chapter) from The Guru Chronicles, telling more of his amazing life.

More of the Story

Around 1850 Rishi began to frequent a small village near Bangalore, returning to beg from the houses often enough to become a familiar sight. He may have been drawn to the Natha mystics who lived in Karnataka state, and felt an affinity with their ways. Like them, he was not your everyday yogi. Always barefoot and empty-handed, he carried no bowl, no staff, no water pot or shawl. He ate once a day, from one house, and only what his two hands could hold. Many had thought of approaching him for blessings or asking him who he was, but Rishi came and went like the wind and did not brook intrusions or the curious. He appeared out of doorways and disappeared just as quickly. He stepped out of the crowd in the marketplace, and before you could catch him he walked around a corner or into a shop and was gone. Where Rishi came from, where he stayed, no one in the village knew. No one had been able to talk to him about such things.

He was described as a man of medium height with a thin, wiry build, intensely active and always in motion. He never strolled or ambled the roads; he marched wherever he was going, strong and straight despite his age. He wore a kavi dhoti (the rusty orange hand-spun, hand-woven, cotton garb of the Hindu saint) and two rudraksha malas, nothing more. His beard was silvery grey, his hair still quite dark, matted and piled in a crown above his head. His eyes, though, are what men remembered most about him—like two dark pools they were, large and round, black as coals and full of fire. They say he was an unusually quiet man, with an aura of unbridled power, like a river at its mouth, like the air before a storm. That heat, that current, was overwhelming, making it hard to be near him for long.

A man named Prasad owned a tea shop in the village, located right off the market square. It was a solid building with concrete walls and a timber-hatch roof, and he made a modest living serving tea, sweets and buttermilk there. Business was brisk, as it is in most Indian tea shops. The rishi walked into his place one morning and sat down on a wooden bench against the back wall. Prasad looked up to see an old sadhu leaning back against the cool wall, resting from the heat outside. Even as he watched, Rishi looked once around the room, pulled his legs up under him and closed his eyes in meditation. Prasad wasn’t sure what to make of it, so he let the holy man be. In this time and place, holy men were revered, and even the most eccentric among them were held in awe, their movements unrestrained by ordinary society.

When it came time to close the shop for the day, Rishi was still sitting there. He hadn’t moved. In fact, he didn’t seem to be breathing at all. Prasad came over. “Has he died?” he wondered. No, the body was warm. He sat by Rishi for over an hour, wondering what to do. Finally, he reluctantly locked the shop and went home, leaving Rishi inside.

The following morning, Prasad found Rishi still in samadhi, exactly as he left him. He hadn’t stirred at all. Word got around quickly, and villagers crowded in through the day to see—standing around, staring at him and talking it over. Despite the commotion, Rishi never moved. His face was radiant, but unmoving, like a mask.

That night Prasad again locked him inside the tea shop, and again the next morning Rishi was there, entranced, upright and unmoving. This went on for days, then weeks, then month after month. Word spread. People started coming from hundreds of kilometers away to see the silent saint. The tale grew more unbelievable each time it was told. In legends such things happened, in folk stories perhaps. Not in a little village in the hills. Not in modern times. And yet, there he was.

The rishi didn’t eat, didn’t drink, didn’t move, didn’t breathe, as far as anyone could tell. He was like a log of wood, like a corpse, but he wasn’t dead, they knew. He was absorbed in God, in samadhi, keeping only a tenuous hold on the physical plane.

Eventually Prasad closed his tea operation and cleared out all the rough-hewn tables and benches. He didn’t mind. His devotion filled him with the confidence that all his family’s needs would always be met, and they were. Once he made the decision to surrender himself to caring for the Rishi and managing the crowds that came every day for darshan, everything always seemed to flow smoothly.

They came from before dawn and stayed until after dark. Some were there for the mystery of it all, and others for the chance to be with philosophically astute comrades. Others were superstitious, and a few were there just to debunk the whole thing. The evenings were always busy, for there were few in the village who didn’t visit Rishi almost daily. Eventually, pilgrims from all corners of India made their way to Bangalore, to be part of history, to see something remarkable.

The crowds grew. It became difficult to keep them from crowding Rishi, as most wanted to touch him, to touch a bit of holiness. Prasad put up a brass railing to keep them back. It worked. Only he and his sons could go beyond it, and at least one of them was on duty whenever the shop was open.

The various offerings people brought were passed over the railing to the “priest” on duty, who spread them out on a low, copper-clad table in front of the bench where Rishi sat. Also within the railing was a row of brass oil lamps, a dozen of them, large and small, no two alike, donated by pilgrims. These were kept burning night and day. A shallow bronze pot was added later, out in front of the railing, where devotees burned great quantities of camphor. The soot from the fires soon blackened the room, especially after Prasad bricked in all the windows for security. The remaining door he bolstered with great iron hinges and bars, and he kept the key to the shop on his person at all times.

His business gone, Prasad maintained his family by taking what he needed each day from the piles of cooked food, fruits, flowers, incense and money the pilgrims brought as offerings. The rest he distributed back to the devotees as prasadam, as temples do after each puja, so little or nothing was left by nightfall. The rishi attracted an astonishing amount of wealth. No one came or went away empty-handed.

Things eventually settled down to a routine, for there was really very little to do or see. People came to be with Rishi, staying a few hours or a few days, and then going. No pujas were done; no one chanted, sang or talked. The room was always silent, the lamps were always lit, Rishi was always there, and this went on year after year after year.

Seven Years in Meditation

A visit to the tea shop was the experience of a lifetime, and many said once was more than enough. Stepping through the iron doorway was like stepping into another world, from the glaring heat of the Indian sun to the cool interior of a cave. One end of the room was illumined by sunlight streaming in through the open door. Only oil lamps lit the far end and the bench where Rishi sat.

You see Rishi first, like an apparition, a wraith against the wall beyond. If chiselled in stone, he would look the same. Ringed by oil lamps, no shadows approach, so his face reflects the ruddy color of fire. He is thin and old, his ribs show through, and he is covered with a film of vibhuti, holy ash, from head to toe. No one applies it, but it is always there, powdering down on the bench and floor, the only thing about him that changes from day to day. Looking at him, the thrill in his limbs is unmistakable; it can be seen. His face is an open expression of indrawn joy, radiant and shining, mingled with the fire glow.

On the table in front are heaps of bananas and mangoes, rice and pomegranates, clay jugs, brass pots, incense and coins all spread in profusion on a gorgeous cloth of red and green. The whole room is strewn with flowers. Everything looks polished and new—the railing, the lamps, the table—everything but the camphor bowl, blackened and bent. It must glow red on a busy day. New straw mats hide the earthen floor, and a few devotees are seated upon them. Prasad stands guard in the shadows, a portly figure in spotless white.

It is perfectly quiet, perfectly still. A ringing silence fills the air and can be heard by those inwardly attuned, a sound as of a thousand vinas playing in the distance, a sound divine, the sound, some say, of the workings of the subtle nervous system, or, others claim, the sound of consciousness itself coursing through the mind, the sound that binds guru to disciple through the ages. It is a sound that many visitors have never heard till now, and it fills them with an inexpressible and familiar joy.

The dim room smells of camphor and earth and the perfume of ripe mangoes piled on the table. It feels alive; it looks empty. Sitting on the mats with the other devotees, one suddenly feels the impact of Rishi’s presence. The skeptical mind is stunned, and it seeks a rational explanation: “He is an old man napping, nothing more. He is asleep or lost in a thought. Surely that’s all.” But for seven years? Seven years he has been here, they say, rapt in his soul, absorbed in God. Can it be believed? It boggles the imagination. The mind struggles and comes away baffled and yet changed by having been here, having been in Rishi’s scintillating presence.

Pilgrims from all over India reached the tea shop in Bangalore, on the 3,000-foot-high Mysore Plateau. Many said they had been called there, having seen Rishi in a dream or vision. Prasad knew a thousand such stories, and delighted in telling them to whomever would listen. The pilgrims came with problems more often than not, and always they were helped; none was denied. Few would claim that Rishi had answered their prayers himself, for no one felt that kind of personality in him. He wasn’t there in that sense. And yet, things happened around him that didn’t happen elsewhere.

In Rishi’s presence the mind was so clear for some pilgrims, so calm, that answers often became self-apparent. Even problems that had gone unsolved for years dissolved in minutes before him. The answers came from within the pilgrim. For others the answers were more elusive, coming after they left his presence, even days later. A visitor would pray or merely think over his life while sitting before Rishi and then be on his way. Whatever the question or problem or need, the answer soon came, clear as a bell—in a scrap of conversation overheard on the street, in a song sung by a child skipping to school, or simply from intuition, from the inner sky.

Sitting with Rishi opened the mind to its depths, and everything adjusted itself naturally. It wasn’t the answer itself but the way it hit the mind, the impact of it, that showed where it came from—it was straight to the point in a roundabout way, said but unsaid, seen but unseen, like Rishi himself. Always the answer hit the nail on the head, with stunning power, leaving no room for doubt. And that power did not diminish with time, as everyday thoughts do, but grew in certainty and clarity.

Then there were the notes. On rare occasions, a pilgrim would receive a note, a message out of thin air, answering problems he had brought, silently, before Rishi. These notes appeared in the room where he sat, written on a scrap of paper. A rustling sound as it hit the floor was all anyone knew of where the note came from. These messages were never personal, never addressed to anyone, and didn’t answer questions specifically. Rather, they spoke in general terms, talking around the subject and usually explaining the way things were done in the old days.

If a mother was worrying about the marriage of her daughter, the note might explain a bit about how marriage was looked at in the Vedas, what the ancients looked for in a family, why a man marries, why a woman marries, how to tell if the choice is good, and so on. Though brief, the notes were more than enough to show what was needed and why. Because they spoke to everyday problems, their content was seldom remarkable. Similar statements could be found in any Hindu scripture. Indeed, the notes occasionally quoted scripture, especially the Upanishads. But the way they were written, and the medium of the message, had a remarkable effect on the one who received it. The language of the notes was usually Kannada, though Telugu, Tamil, Hindi, Sanskrit—and even German, on one occasion—were also used.

A widowed businessman came from Tuticorin, deep in the South of India, after finishing his career and leaving the estate in his son’s hands. Bringing no plans, no problems, no needs, he simply came to see Rishi. A note appeared while he was there, referring to the four stages of life—brahmacharya, grihastha, vanaprastha and sannyasa (student, householder, elder advisor and renunciate)—which are the natural patterns of the soul’s earthly vitality and karma. The man captured the subtle direction and entered a life of service in a nearby ashram, visiting Rishi often.

Five years after Rishi had come to the tea shop, four young men, students at the University of Berlin, arrived in the village to see him. They were all in their early twenties, all Sanskrit scholars, three of them quite competent. Like many of their generation, they were enthralled by the Vedas and Upanishads. They had even founded an ashram in Germany to spread the lofty teachings they so admired.

These four had heard about Rishi from travelers in far away Berlin and decided to come to India to see him for themselves. If the reports were true, he was just the man they were looking for to guide them in practicing and realizing the ideals of the Upanishads. Two of them were wealthy enough to pay passage for four out of pocket, and so—their hearts aglow with dreams and plans, pinning their hopes on bringing Rishi back to the fatherland to head up their ashram—they shipped off to India.

Landing in Bombay, they proceeded south to Bangalore and the village where Rishi sat. Because they spoke only Sanskrit, of the Indian dialects, a brahmin man accompanied them as a guide and translator. The people of the village were impressed with their sincerity and a bit surprised by their knowledge of Hinduism. They were hosted and entertained by the best of families, treated like princes and practically adopted by everyone. They would gladly have stayed on forever, if not for their comrades in Berlin and the mission they had come East to fulfill.

Once they met Rishi, their world turned around him alone. They spent two days sitting in the tea shop, coming outside only to hear Prasad’s stories. After two weeks, each of them had their own stories to tell, of wonderful experiences, inner and outer. The rishi surpassed their wildest dreams. They were sure they had found their teacher. The future of Hinduism in Germany looked bright. They talked about it excitedly: Could Rishi be aroused? Would he even speak? Could he travel in his present state? Dare we disturb him? Most important, would he agree to go to Berlin? What if he refused? Then what?

A message materialized one day, the kind Prasad always talked about, written in German and obviously meant for them alone. That note convinced them utterly. They were walking on air for days afterward, reciting it to each other like a hymn, like a mantra. The note was in Rishi’s usual style, indirect, talking all around the question, yet plain enough:

“All things can be—according to karma and opportunity. A man’s karma is threefold: that which awaits a future birth, that which awaits an opportunity and that which is in motion now. Sadhana spares the least of men a thousand future lives.”

There were other foreign visitors to the little tea shop during the following two years, though no one ever again tried to disturb Rishi. Life went on as it always had, until one day Rishi opened his eyes and looked at everyone present. A few minutes later, he stood up, stepped out of the shop and walked down the road. He had taken great care during those years, through practice of pranayama, to maintain the flow of life through his body. So he was able to get up and move about with the merest instability, more like someone who had sat in one position for too many hours.

Oooh, love the aged golden glory effect on this ai assist art, makes us transported into the days of yore…very cool